In a perfect world, storage is easy. You put a file somewhere. You come back later. It is still there. Nothing lies. Nothing disappears. Nothing quietly swaps your data for something else.

But decentralized systems do not get to live in that world. They live in the world we actually have. Machines crash. Operators cut corners. Networks split. Some participants behave badly on purpose. And sometimes, the system cannot even tell which kind of failure it is looking at.

This is where the old term Byzantine fault becomes useful. It describes failures where a participant may act arbitrarily, offline, buggy, or malicious, and you cannot rely on them to follow the rules. In storage, that could mean refusing to serve data, serving corrupted pieces, pretending to store data, or trying to waste other nodes’ resources.

@Walrus 🦭/acc is designed with that world in mind. It is a decentralized storage protocol for large, unstructured content called blobs. It stores blob contents off-chain on storage nodes and optional caches, and it uses the Sui blockchain for coordination, payments, and availability attestations. Only metadata is exposed to Sui or its validators. This separation matters because Walrus wants the chain to record “what is true” about storage without forcing the chain to carry the storage payload.

To understand how Walrus handles Byzantine behavior, you need to understand two simple ideas: shards and assumptions.

A shard is a unit of storage responsibility. Walrus erasure-encodes blobs into many encoded parts and distributes those parts across shards. Storage nodes manage one or more shards during a storage epoch, which is a fixed time window. On Mainnet, Walrus describes storage epochs lasting two weeks. During an epoch, shard assignments are stable, and a Sui smart contract controls how shards are assigned to storage nodes. That means the question “who is responsible right now?” has a clear, public answer.

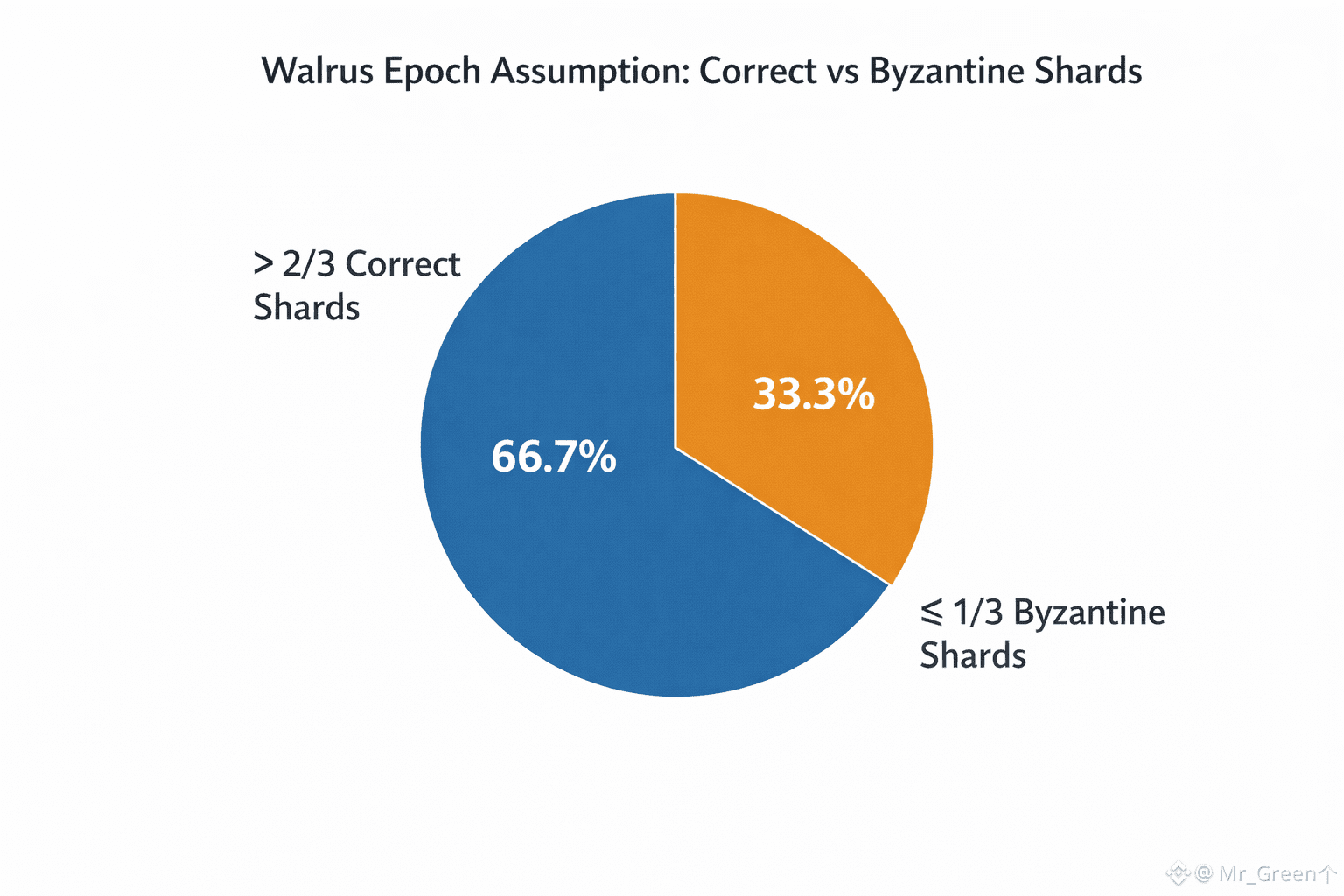

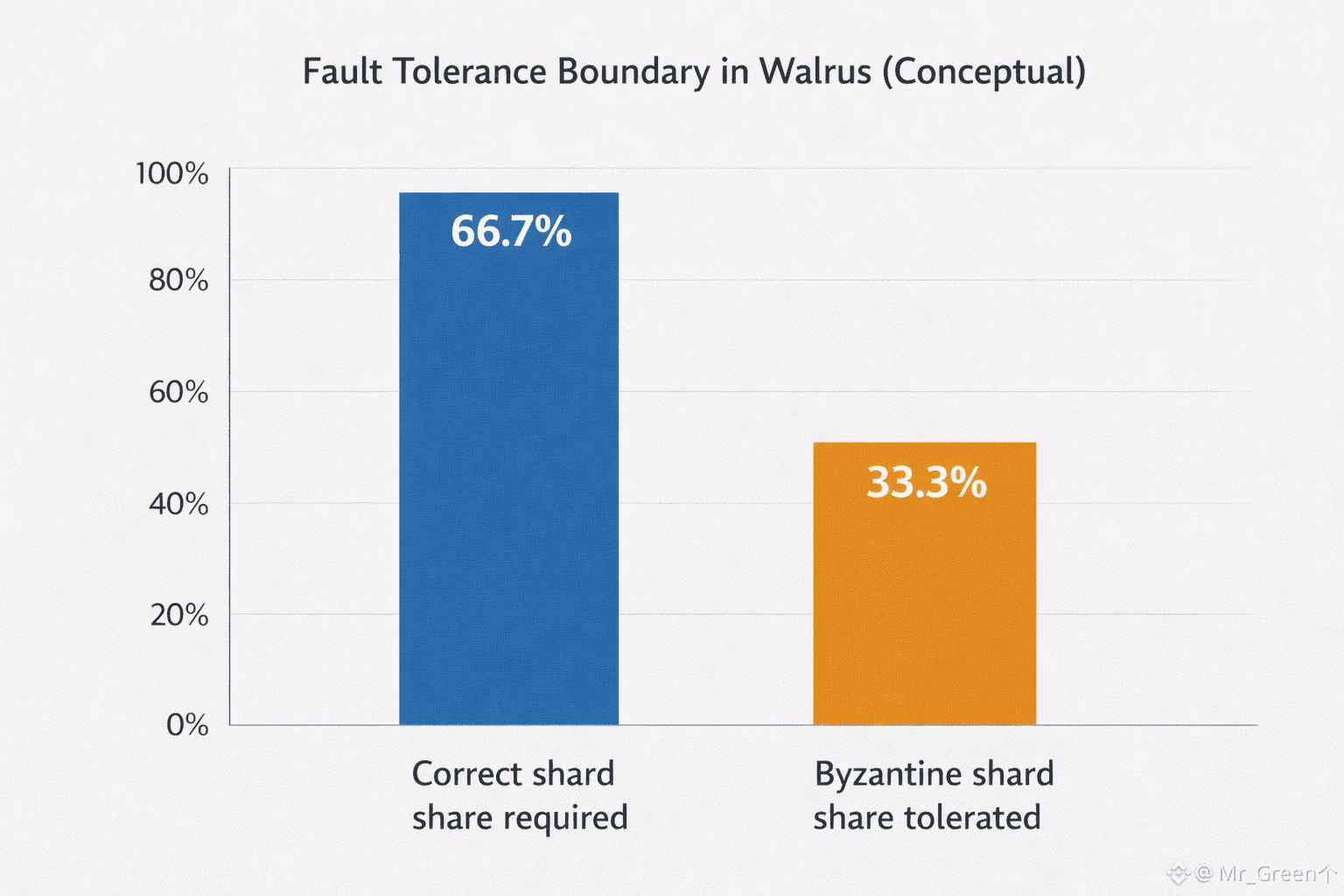

Now comes the part that sounds strict but is actually realistic: Walrus assumes that more than two-thirds of shards are managed by correct storage nodes within each storage epoch. It tolerates up to one-third of shards being controlled by Byzantine (malicious or faulty) storage nodes. That is the safety boundary Walrus is willing to live inside.

This is not Walrus being pessimistic. It is Walrus being honest. It is saying: “We do not need everyone to behave. We need enough of the system to behave.”

Why does the “two-thirds” line matter so much? Because it draws a clear line between a network that can recover and a network that cannot. If the majority is correct, you can reconstruct truth from the parts that still follow the protocol. If too much of the system is dishonest or broken, then there may not be enough good material left to rebuild the blob reliably. Walrus does not pretend otherwise.

The “one-third tolerance” is also tied to how Walrus stores data. Walrus uses erasure coding (RedStuff) to encode blobs into many pieces, called slivers, that are distributed across shards. Erasure coding is designed so the original blob can be reconstructed from a subset of pieces, not necessarily all of them. This is important because it means a reader does not need perfect cooperation from every node. The system is built to survive partial failure. It is built to survive missing pieces.

But Byzantine resilience is not only about getting enough pieces. It is also about knowing the pieces are real.

If a malicious node sends random bytes, the system needs a way to reject them. Walrus uses a blob ID derived from the blob’s encoding and metadata. That blob ID acts as a commitment, so clients and nodes can authenticate the pieces they receive against what the writer intended. This shifts trust away from the node and toward verification. The node can claim anything. The client can check.

This is a subtle theme in Walrus: verification happens at the edge. The system does not ask you to believe a gateway. It gives you tools to test what you received.

The two-thirds assumption also shapes how Walrus coordinates responsibility across time. Because shard assignments live inside epochs, Walrus can say: “For these two weeks, this committee is accountable.” That helps in two ways. First, it stabilizes operations. Nodes know which shards they must serve, and clients know which nodes to talk to. Second, it gives the protocol a clean way to rotate responsibility. If some operators underperform, the system is not stuck with them forever. Epoch transitions give the network a recurring chance to change who holds responsibility.

There is also a practical reason to state assumptions clearly: it tells builders how to design safely.

If you are building an application that depends on Walrus for large data, media files, audit packs, proof bundles, archives, you want to know what kind of failure the system is built to handle. Walrus is built to handle some nodes being down and some nodes being malicious. It is not built to handle a world where most of the system is hostile. That boundary is not a weakness. It is the difference between a meaningful guarantee and a vague promise.

It also changes how you think about “availability.” Walrus defines a Point of Availability (PoA), the moment when the system takes responsibility for maintaining a blob’s availability for a specified period. PoA is observable through events on Sui. That means, for builders, availability is not only a feeling. It is a state you can reference. It is a timestamp you can point to. It is a time window you can reason about.

In a Byzantine setting, that time window matters. A blob is not only “stored.” It is stored under a system rule that says: within this availability period, assuming the epoch’s fault tolerance conditions hold, correct users can retrieve a consistent result. That kind of statement is far more useful than “it should be there.”

Walrus also makes a clear choice about what happens when things go wrong in a way that cannot be repaired cleanly. If a blob is inconsistently encoded or later proven inconsistent, Walrus describes mechanisms that can mark it as inconsistent so reads return a clear outcome (often resolving to None) rather than allowing a blob ID to produce different content for different readers. In distributed systems, a clean failure is sometimes the only way to protect shared meaning.

So what does “Byzantine tolerance” feel like in everyday terms? It feels like walking into a library where some shelves are missing and some librarians are unhelpful, but enough of the catalog is honest that you can still find the book you asked for, and you can confirm it is the correct book when you open it. You may have to ask more than one person. You may have to cross-check. But the system does not collapse just because a few participants behave badly.

That is the core of Walrus’s two-thirds assumption. It is a line drawn in the sand that says: “We can withstand a minority of chaos.” Not because chaos is rare, but because chaos is normal.

For developers, this is a practical promise. It means you can build systems that treat Walrus as a robust storage layer under realistic adversarial conditions. For DeFi builders, it means large evidence can live off-chain while still being verifiable and time-bound, rather than living inside a single server’s goodwill. For client builders, it means you can support HTTP delivery paths and caches for speed, while still relying on verification rules to protect correctness.

Byzantine fault tolerance is not a dramatic feature. It is a quiet refusal to be naive. Walrus does not ask the world to behave. It tries to keep working even when the world does not.