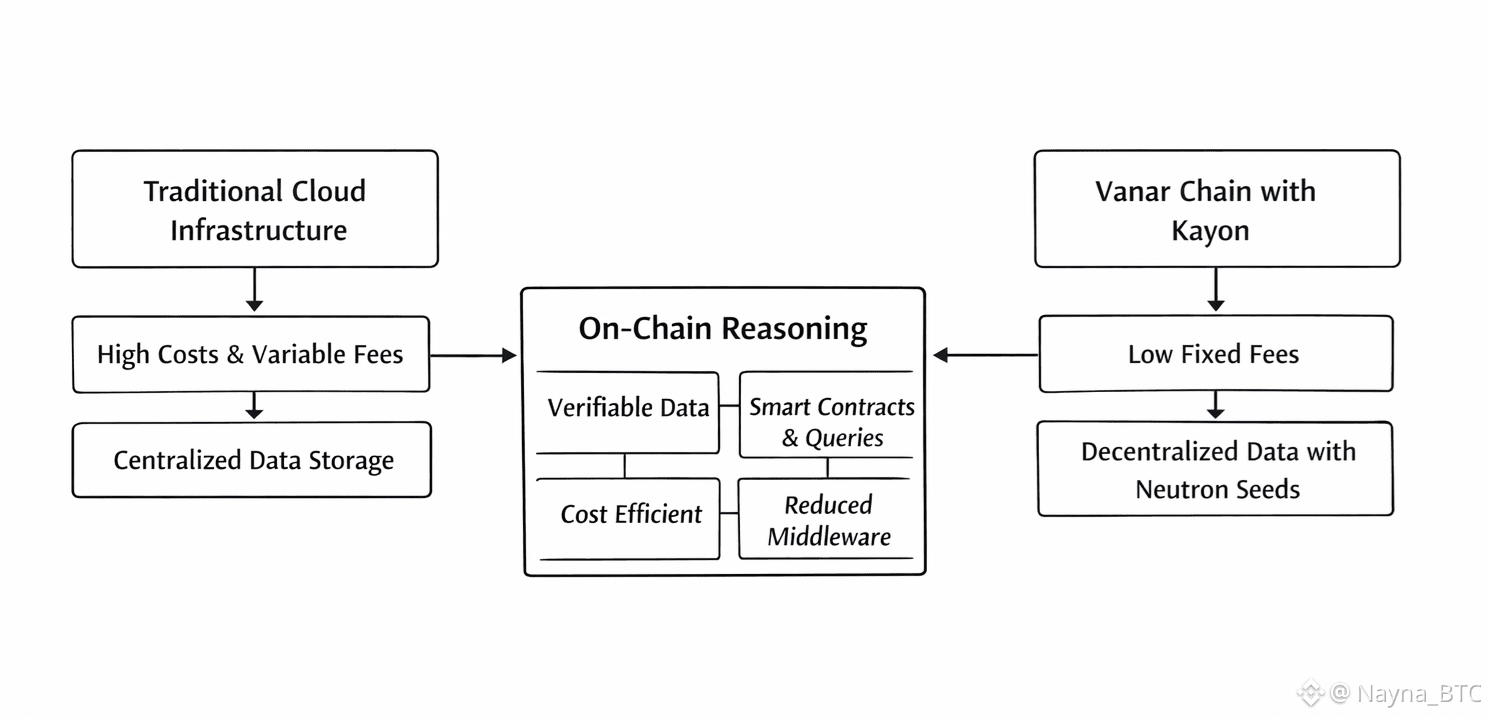

Software stacks grow to know a pattern, complexity rarely arrives with a warning, it arrives as “just one more layer.” Traditional cloud infrastructure made it easy to ship quickly, but it also trained teams to accept cost surprises as normal. When I dig into Vanar Chain, what keeps pulling me back is not speed for its own sake. It is the attempt to treat infrastructure as something you can reason about, not just rent. And in Vanar’s world, that idea is unusually literal, because Kayon is built to reason on-chain, on top of data that the chain can actually verify.

“Pay as you go” felt like freedom. It stays that way right up until a product finds real users, then the bill turns into a second backlog. The painful part is not even the absolute cost, it is the variance. Traditional clouds charge for storage, compute, bandwidth, and the quiet penalties hidden in the edges. The system is centralized, so your application’s trust boundary and your cost boundary are both managed by someone else. To me, decentralization only matters if it also reduces those boundary surprises. Otherwise it becomes ideology with invoices.

What I keep looking for is cost control that is structural, not negotiated.

Kayon is trying to move a class of “business logic” that usually lives off-chain back onto the chain. Kayon is described as an on-chain reasoning engine that lets smart contracts and agents query and reason over live, compressed, verifiable data. That is a different ambition than bolting AI onto an app. It reads more like an infrastructure choice, make the chain not just a ledger, but a place where logic can check facts it can actually attest to, without depending on fragile middleware.

Most “decentralized storage” stories quietly end in a pointer. A hash, a link, a promise that the file is “somewhere.”

Vanar’s Neutron layer is framed differently, it compresses and restructures data into programmable “Seeds,” small units of knowledge designed to be verifiable and usable by AI-native logic. In public coverage, Neutron is associated with compression ratios up to 500:1, with a casual example of shrinking a 25 MB file to around 50 KB as a Seed. If that holds in practice, the cost conversation changes, because you are no longer paying to keep bulky blobs alive in someone else’s storage silo.

The cloud is excellent at running code, but it is not designed to prove anything about the data it serves you. It serves, it does not attest. With Kayon sitting above Neutron, the chain is trying to become a place where data and logic meet in a verifiable way. I keep coming back to a simple mental model, instead of “fetch data, trust it, then act,” it becomes “query data, verify it, then act.” The shift sounds subtle, but it can remove entire classes of infrastructure spend, because fewer components need to be maintained just to keep trust glued together.

I remember the first time a team asked me for a “monthly cap” on infrastructure, and I had to explain why it was harder than it should be.

Vanar’s documentation talks about a fixed fee model, where transaction fees are set in terms of a dollar value of the gas token to keep costs predictable for dApps. I am careful with promises like that, but I respect the intent. If you can treat transaction cost like a known unit, you can design systems that do not panic when usage spikes. Cost control is not just cheaper fees, it is knowing what “success” will cost before it arrives.

Performance talk is cheap unless it comes with explicit constraints. Vanar’s architecture docs describe a 3-second block time and a 30,000,000 gas limit per block as part of its throughput design. I like seeing numbers because they force tradeoffs into the open. Short blocks can reduce waiting time for state updates, which matters if Kayon-style reasoning is meant to be interactive, not delayed. And a clear block gas ceiling matters because it shapes worst-case compute demand. This is the kind of “infrastructure first” thinking that tends to be built quietly, under the surface, without marketing noise.

Mnetworks fail in ways that were not technical, they were operational. Governance, validator incentives, and upgrade paths matter more than slogans. Vanar’s docs discuss staking with a Delegated Proof of Stake mechanism to complement a hybrid consensus approach, with the stated goals of improving security and decentralization while letting the community participate. The detail that matters to me is not the label, it is the implication that the network is designed to be operated by a set of participants, not a single operator. If Kayon is going to be trusted as a reasoning layer, the base layer needs that operational plurality.

Most cost does not come from “compute,” it comes from coordination. Pipelines, ETL jobs, indexes, caches, permission layers, and the people babysitting them. Kayon’s pitch is that contracts and agents can reason over verifiable data directly, rather than pulling it into yet another off-chain database just to make it usable. That is the kind of change that, if it works, reduces both spend and fragility.

I have learned to value boring reliability over clever architecture, and ironically this is how you get there, by deleting components, not adding them.

“Decentralization with cost control” only stays true if you can measure the levers that move cost. If I were building on Vanar with Kayon, I would keep a quiet dashboard of a few boring variables:

i. Seed size distribution, because compression wins only matter if they stay stable across real data.

ii. Query frequency and scope, because reasoning can become expensive if developers treat it like free search.

iii. Fee predictability over time, since the point of fixed fees is budgeting, not headlines.

iv. Validator health and staking concentration, because decentralization is an operational property, not a philosophical one.

To me, this is where “quietly building” becomes real, the discipline to watch the unglamorous metrics.

People treat “cloud vs chain” like a binary. It never is. Traditional cloud infrastructure is still a strong fit for bursty compute, heavy model training, and workloads that do not benefit from verifiability.

Vanar is not the fantasy of replacing everything. It is the ability to relocate the parts of the stack where trust and cost variance hurt the most. Neutron’s idea that data can be anchored on-chain for permanence or kept local for control is interesting here, because it suggests a spectrum rather than a dogma. To me, cost control often means choosing the right home for each type of state.

A network token should behave like infrastructure, not like a lottery ticket. Vanar’s documentation is clear that VANRY is used for transaction fees (gas) and that holders can stake it within the network’s staking mechanism. In a Kayon-centric world, that matters because every query and every on-chain action has to be paid for in a way developers can plan around. If fixed-fee ideas hold, the token becomes part of a predictable operating model, closer to fuel and security deposit than to a marketing prop. Depth over breadth, infrastructure first, not loud.

I remember the last cycle’s obsession with shiny apps, and how quickly many of them disappeared when the subsidized costs ran out. What I keep noticing now is a quieter shift, teams are tired of fragile stacks and unpredictable spend. When I dig into Kayon on Vanar, the appeal is not spectacle, it is the chance to make reasoning, verification, and cost budgeting part of the same substrate. Neutron Seeds, fixed fees, and an on-chain reasoning layer are not “features” to me, they are an attempt to simplify the trust story while keeping the bill legible. I have watched networks chase breadth and burn out. I keep coming back to depth, built quietly, under the surface, with infrastructure as the main character.

Near the end, I will admit something I usually avoid saying, I do not watch $VANRY’s spot price closely, because price is loud and infrastructure is patient. If the engineering keeps compounding, the market will do what it always does, oscillate, overreact, then eventually notice what was quietly built.

Quiet systems outlive loud cycles.