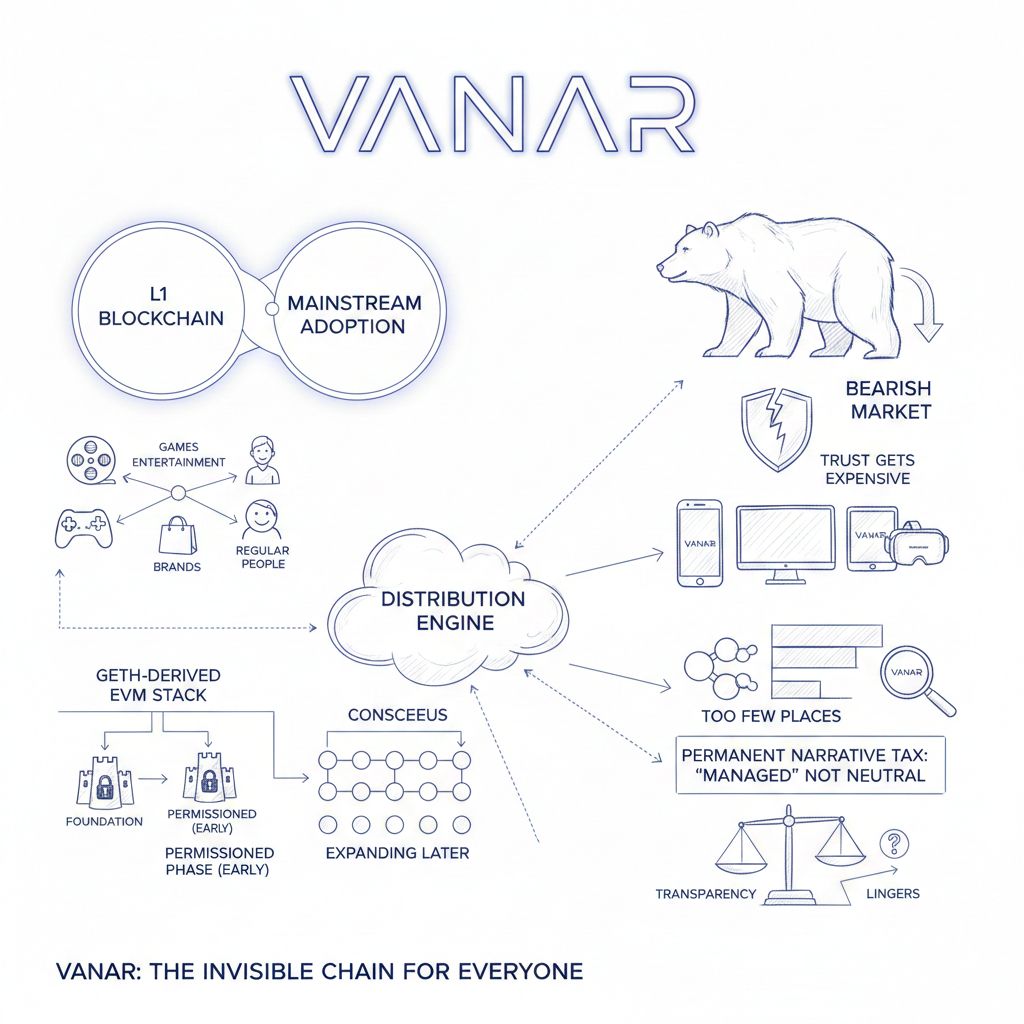

Vanar’s story is basically: “build an L1 that regular people might actually touch,” and use games, entertainment, and brands as the distribution engine. That’s a sensible angle—because in real-world adoption, the chain that wins isn’t always the most technical, it’s the one that feels invisible: cheap, predictable, stable, and safe. But that same “mainstream-first” approach also creates very specific ways things can go wrong, especially when markets turn bearish and trust gets expensive.

The cleanest bear case isn’t that Vanar can’t ship. It’s that Vanar ends up with too much trust concentrated in too few places at exactly the moments the market becomes least forgiving. Vanar’s own materials describe a Geth-derived EVM stack and a consensus approach that starts with a more permissioned phase (foundation-run validators early on, expanding later). That’s a practical bootstrapping route, but if it lingers too long or isn’t transparently measured, it becomes a permanent narrative tax: outsiders treat the chain as “managed,” not neutral infrastructure.

The most dangerous “one bad day” risk is the bridge surface. Anytime value moves between chains, the bridge becomes the brightest target. In a bearish environment, attackers aren’t trying to impress anyone—they’re trying to extract. Vanar has discussed bridging and wrapped flows across EVM networks, so the risk isn’t hypothetical: if bridge security relies on a small signer set, or if keys get compromised, or if message verification has a subtle bug, the loss can be large and the reputational hit can last for years. The chain doesn’t just lose funds; it loses the one thing consumer ecosystems can’t function without: basic confidence.

How Vanar survives that isn’t glamorous, but it’s real: you make bridging boring. That means hard operational security (segmented signing, rotation, monitoring), controls that slow down catastrophe (limits, delays, circuit breakers for large withdrawals), and public proof that someone tried to break it before the world did (audits, bug bounties, and a track record of fixes). Over time, the strongest path is shifting away from designs that require “trust the signers” toward designs that minimize trust wherever possible. The market rewards that shift because it replaces reputation with verification.

The next failure mode is less dramatic but more corrosive: liveness and censorship concerns caused by a small or tightly coordinated validator set. If a few validators can halt the network, or if it’s easy to imagine pressure causing selective transaction inclusion, builders quietly decide they’d rather deploy somewhere else. Vanar’s documentation and whitepaper both imply an early-stage model where the foundation runs validator nodes before opening participation more broadly. Again, that can be normal at launch—but in a bear market, credibility is earned with numbers, not promises.

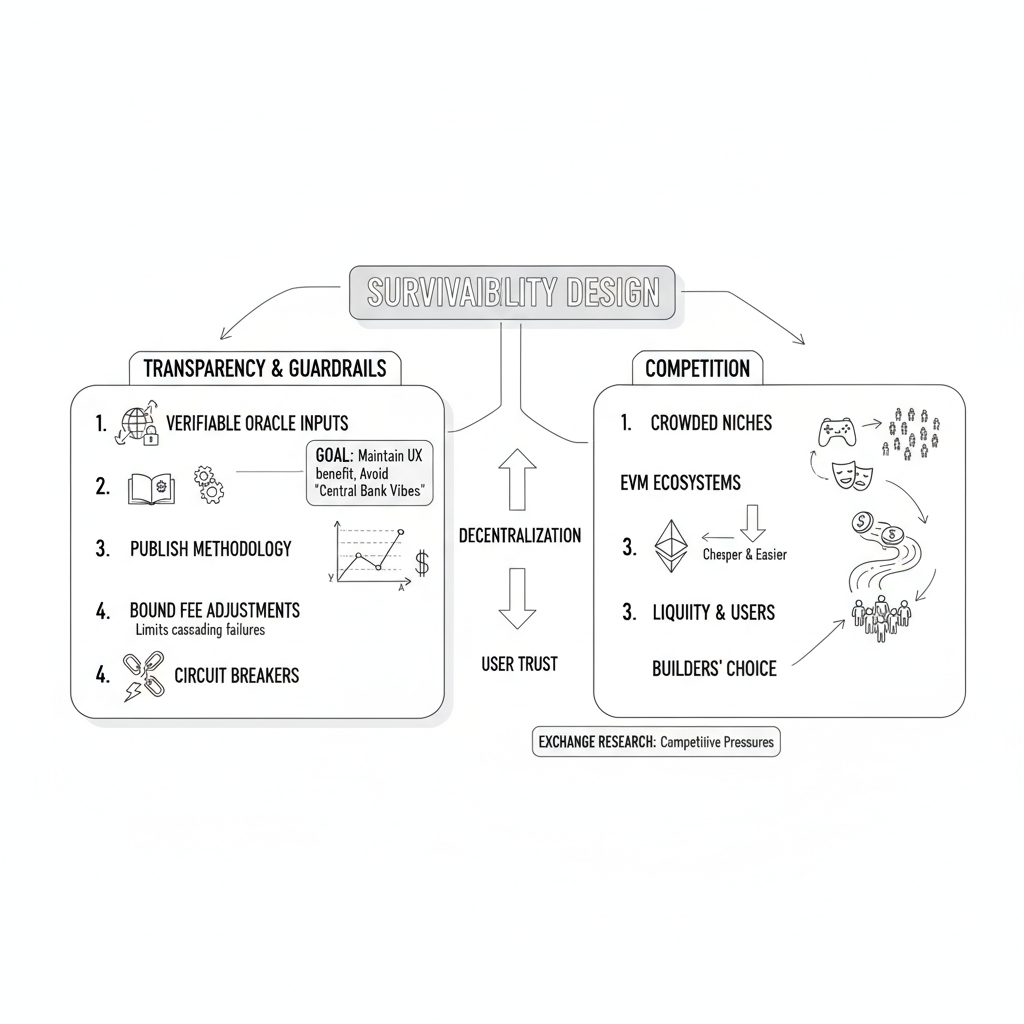

The survivability move here is to make decentralization measurable. Not aspirational, measurable. Validator count targets, diversity targets (hosting, geography, operators), clear rules for validator onboarding and removal, upgrade processes that can’t be rushed, and timelocks so the community can see changes coming. When chains don’t do this, people assume the worst—even if the team is acting in good faith—because the incentives during a crisis are always suspect.

Then there’s a consumer-chain problem that looks small until it isn’t: most users won’t get hacked at the base layer. They’ll get drained by approvals, fake sites, compromised front-ends, or sloppy smart contracts in games and marketplaces. A chain that wants “the next billions” has to be unusually strict about ecosystem hygiene. You can have perfect consensus and still watch the community get wrecked by wallet scams and insecure dApps. Survival here looks like shipping “safe defaults”: vetted templates, audits for flagship apps, monitoring, wallet-level transaction simulation, and warnings that prevent people from signing their life away.

Regulation is the slow choke risk. Vanar’s narrative touches mainstream verticals and increasingly finance-adjacent territory (AI, infrastructure, payments themes). Even if the chain is neutral infrastructure, the token and staking/governance features can drag the project into uncomfortable categories depending on jurisdiction and how things are marketed. VANRY is positioned as the gas token with staking and governance roles, which is common—yet in certain regions, common doesn’t mean low-risk. Exchange-facing disclosures also highlight how actively venues evaluate these risks and competitive positioning.

The bear outcome isn’t necessarily a dramatic ban—it’s gradual loss of access: staking restrictions here, market limitations there, partners hesitating because compliance boundaries aren’t clear. The survivability strategy is disciplined: keep the base layer neutral, avoid messaging that sounds like “return on effort of others,” provide clear risk disclosures, and offer optional compliance tooling at the application layer rather than baking heavy constraints into the whole network.

Token dynamics are where bear markets squeeze the hardest. Public market sources commonly cite a 2.4B max supply, and Vanar’s whitepaper discusses genesis allocations and ongoing issuance through block rewards. When activity is weak, inflation-funded incentives can become persistent sell pressure: validators and participants sell to cover costs, price drifts down, and it gets harder to attract builders without spending even more. It’s not a single collapse—it’s erosion.

Vanar survives that by making emissions “earn their keep.” Incentives should buy retention and real usage, not temporary spikes. The healthiest version is when the chain starts collecting meaningful fees from real users—ideally through the products Vanar highlights—so security and growth aren’t purely dependent on printing tokens.

One subtle but important risk is the project’s “predictable fee” goal. The whitepaper describes determining transaction charges using the dollar value of the gas token and having the foundation calculate price using on-chain and off-chain sources and integrate it into the protocol. That’s great for mainstream UX—nobody likes fees swinging wildly—but it introduces a trust lever: if users feel fees are effectively being set by a central actor, or if price inputs can be manipulated, it becomes another credibility weak point.

The survivability version of that design is transparency and guardrails: use verifiable oracle inputs, publish the methodology, bound the rate of fee adjustments, and add circuit breakers so one bad input can’t distort the whole network. The trick is keeping the UX benefit without inheriting “central bank vibes.”

And finally, the quiet killer: competition. Gaming and entertainment-focused chains are crowded, and even general-purpose EVM ecosystems keep getting cheaper and easier. Even a well-built chain can lose simply because builders choose where liquidity, users, and tooling already are. Exchange research notes explicitly call out competitive pressures in this area.

So the survival bet for Vanar is not “be everything.” It’s “be inevitable in one lane.” If the project’s product suite is real distribution—games, metaverse, brand integrations—then the chain should turn that into measurable, repeat usage that still exists when speculation disappears. In a bear market, that’s the moat: transactions that happen because people are playing, collecting, participating, not because they’re farming.