When performance breaks in DeFi, the first instinct is to blame the chain.

Blocks are too slow.

Fees are too volatile.

Throughput is too low.

The solution, people assume, is obvious: migrate to something faster.

But the uncomfortable truth is this:

If your application collapses under moderate load, the problem may not be the base layer.

It may be your architecture.

High-performance environments like Fogo’s SVM-based runtime expose this quickly. Not because they are magical, but because they remove excuses. Parallel execution exists. Low-latency coordination exists. The runtime can process independent transactions simultaneously — if those transactions are actually independent.

That last condition is where most designs quietly fail.

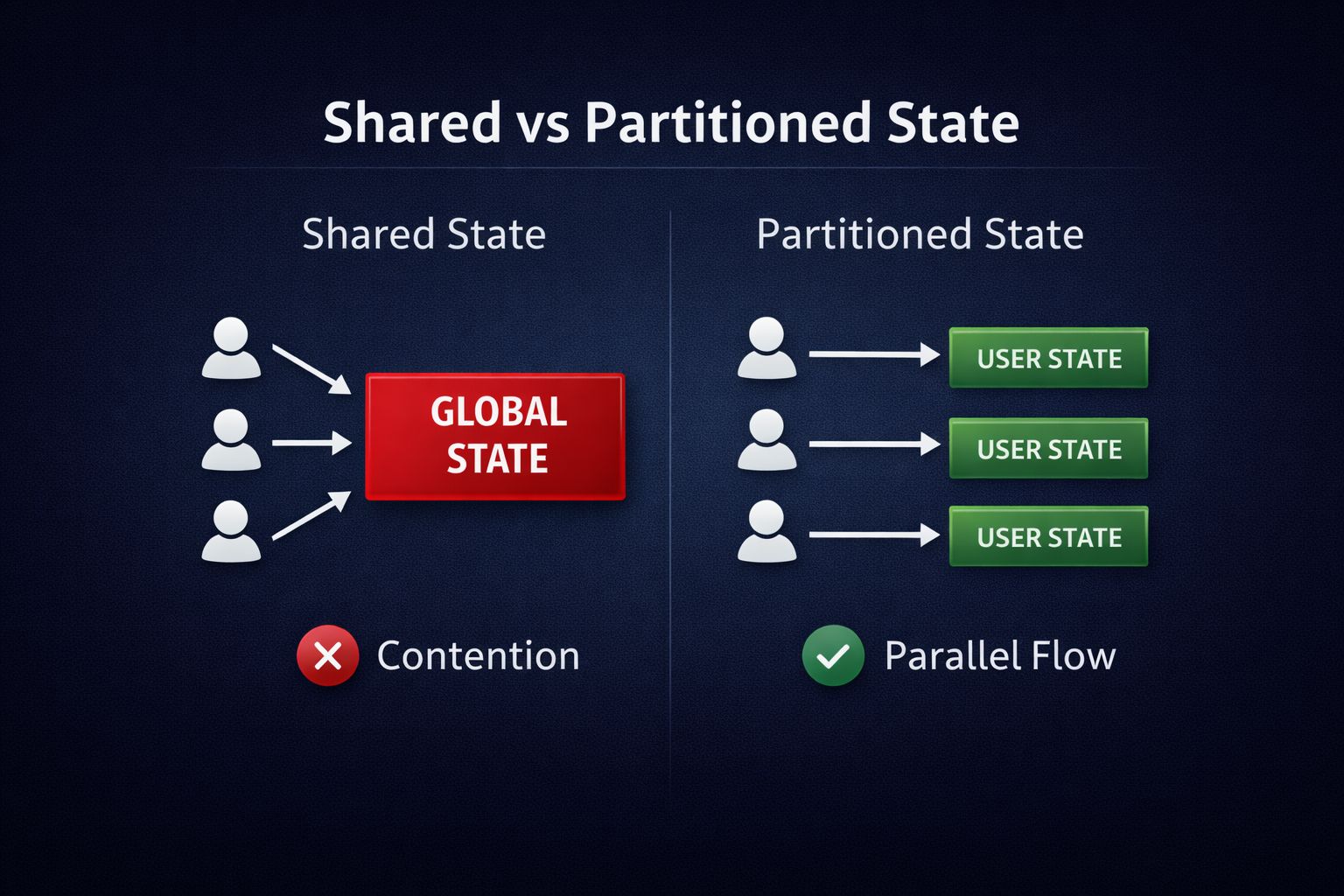

Many DeFi protocols centralize state without realizing the cost. A single global order book account updated on every trade. A shared liquidity pool state touched by every participant. A unified accounting structure rewritten on each interaction.

From a simplicity perspective, this feels clean. One source of truth. Easy analytics. Straightforward reasoning.

From a concurrency perspective, it is a bottleneck.

When every transaction writes to the same state object, the runtime is forced to serialize them. It does not matter how fast the chain is. It cannot parallelize collisions. The application becomes a single-lane road running on top of a multi-lane highway.

Then when activity increases, the queue grows. Traders experience delay. Execution feels inconsistent. And the blame returns to the chain.

But the chain did not centralize your state.

You did.

This distinction becomes clearer in systems designed around explicit state access. In an SVM environment, transactions declare what they will read and write. The runtime schedules work based on those declarations. If two transactions touch different accounts, they can execute together. If they overlap, one waits.

Performance is conditional.

This changes how we should think about scaling. Speed at the base layer is necessary, but it is not sufficient. The real multiplier is architectural discipline at the application layer.

Consider two trading applications deployed on the same high-performance chain. Both benefit from low-latency block production. Both have access to parallel execution.

One isolates user balances and partitions market state carefully. Shared writes are minimal and deliberate.

The other maintains a central state object updated on every action.

Under calm conditions, both appear functional. Under stress, they diverge dramatically. The first degrades gradually. The second stalls abruptly.

Same chain. Different architecture.

High-performance chains do not automatically create high-performance applications. What they do is make design flaws visible sooner. A shared counter updated on every trade becomes an immediate contention point. A protocol-wide fee accumulator written synchronously introduces unnecessary serialization. Even analytics logic embedded in execution paths can throttle concurrency.

None of these choices feel dramatic during development. They often simplify reasoning. They make code cleaner. They reduce surface area.

But they trade future scalability for present convenience.

When builders move to faster chains expecting instant performance gains, they sometimes carry sequential assumptions with them. They build as if transactions must be processed one after another. They centralize state for ease of logic. They assume the base layer will compensate.

It will not.

Parallel execution is not a cosmetic feature. It is a contract between the runtime and the developer. The runtime promises concurrency if the developer avoids artificial contention. Break that contract, and the speed advantage disappears.

This is why blaming the chain is often premature.

If an application requires ever-increasing base-layer speed to remain usable, that may indicate structural inefficiency. No amount of faster consensus can fully offset centralized state design. At some point, contention simply scales with usage.

Chains like Fogo, built around high-throughput financial workloads, raise the bar. They make it possible to build systems that handle dense activity. But they also demand that builders treat state layout as a performance surface, not just storage.

Partition user state aggressively.

Minimize shared writable objects.

Separate reporting logic from execution-critical paths.

Design with concurrency in mind from the beginning.

These are not optimizations. They are prerequisites in high-frequency environments.

The narrative that “we just need a faster chain” is comforting because it externalizes responsibility. It suggests scaling is someone else’s problem.

But sustainable performance rarely works that way.

Base-layer speed provides capacity.

Application architecture determines whether that capacity is used — or wasted.

And in performance-oriented ecosystems, wasted capacity becomes visible very quickly.