Hey Binancian!

In the foundational texts of the cryptocurrency revolution, one word is treated with almost religious reverence: Immutability. The ability to write a record that can never be erased, altered, or censored is the bedrock of Bitcoin and Ethereum. It is what allows us to trust a digital ledger without a bank. For financial transactions, immutability is a feature. But as we transition from storing money to storing data, we are discovering a complex and uncomfortable truth: for digital files, immutability can be a bug.

We are currently witnessing a rush to build the "Permaweb"—a version of the internet where everything uploaded is stored forever. Protocols like Arweave have championed this vision, selling the dream of a Library of Alexandria that can never burn. While noble, this vision ignores the messy, legal, and dynamic reality of the world we live in. Data is not static; it is a living thing. It ages, it becomes obsolete, it becomes illegal, and sometimes, it simply needs to be forgotten.

This brings us to the unique value proposition of the Walrus protocol. While its competitors are fighting to build the most unchangeable hard drive in history, Walrus is building something far more practical and revolutionary: a decentralized storage network that allows for deletion. By introducing the concept of mutability to decentralized storage, Walrus is not just solving a technical problem; it is solving the single biggest barrier to enterprise adoption of Web3.

The Trap of the "Forever" Web

To understand why Walrus’s approach is so critical, we must first look at the "Toxic Data" problem facing permanent storage networks.

Imagine you are a social media startup building a decentralized Twitter. You decide to use a "permanent" storage protocol to host user images. It works great until a user uploads a piece of copyrighted content, or worse, illegal imagery. On a truly immutable, permanent blockchain, that image is now etched into the history of the network forever. You cannot delete it. The nodes storing it cannot delete it without forking the network. Suddenly, every participant in the network is potentially liable for hosting illegal content. The immutability that was supposed to be a shield becomes a legal weapon pointed at the project.

This scenario is the nightmare of every General Counsel at every major corporation. Companies operating in the European Union must comply with GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation), which explicitly grants users the "Right to be Forgotten." If a user asks Facebook to delete their data, Facebook must be able to wipe it from their servers. If that data is on a permanent blockchain, compliance is physically impossible. This incompatibility has effectively walled off the entire enterprise sector from the benefits of decentralized storage.

The Walrus Architecture: Flexible by Design

Walrus breaks this deadlock by reimagining the relationship between time and data. Instead of selling "forever," Walrus sells "epochs."

In the Walrus ecosystem, storage is treated as a renewable resource. When a user or a developer uploads a "blob" (a file) to the network, they pay for it to be stored for a specific duration. This is similar to how we lease real estate or pay for traditional cloud storage, but with the added security of decentralization.

When that duration expires, one of two things happens. The user can pay to renew the storage, keeping the data alive, or they can let it expire. If it expires, the network’s "garbage collection" mechanisms kick in. The nodes are free to delete the old shards to make room for new, paying data.

This sounds simple, but the technical implications are profound. It means that Walrus gives users and applications sovereignty over the lifecycle of their data. A developer can now build a decentralized application that is fully compliant with local laws. If a court orders a piece of data to be removed, or if a user exercises their right to be forgotten, the developer can stop paying for that storage slot, and the data will naturally fade from the network.

Solving the "Toxic Data" Problem

This flexibility protects the node operators—the people running the servers. In a permanent network, running a node is a high-risk activity because you never know what un-deletable file you might end up hosting 20 years from now.

Walrus changes the risk profile. Because data requires active payment and renewal to persist, the system naturally filters out "junk" data over time. Furthermore, the architecture allows for the targeted removal of specific blobs without compromising the integrity of the entire network. If a specific file is flagged as malicious, it can be dropped by nodes without breaking the consensus of the Sui blockchain that governs the network.

This makes Walrus the first "Safe-for-Work" decentralized storage layer. It provides the censorship resistance we want (protecting political speech and open-source code) without the anarchy we fear (permanent hosting of illicit material). It strikes the delicate balance between freedom and responsibility.

Efficiency Through Obsolescence

Beyond the legal arguments, there is a practical argument for deletion: Efficiency.

The vast majority of data generated by humanity is temporary. Think about the weather forecast for last Tuesday, a draft version of a college essay, or a backup of a video game that has since been patched. This data has value in the moment, but it has no value in a decade. Storing this "digital exhaust" forever is a waste of energy and hardware.

Permanent storage networks are essentially digital landfills. They have no way to recycle space. Over time, the network becomes bloated with petabytes of useless, abandoned data that every new node must acknowledge. Walrus, with its epoch-based model, acts more like a biological system. It recycles. Unwanted data decays and is removed, freeing up resources for new, relevant information.

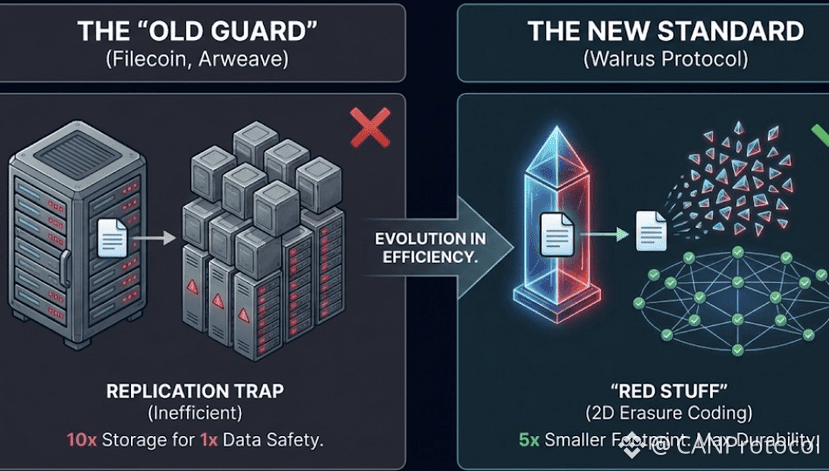

This efficiency is powered by the "Red Stuff" erasure coding mentioned in previous analyses. Because the network is so efficient at breaking down and reconstructing files, the process of adding and removing data is fluid. The network breathes. This dynamic nature keeps storage costs low. You are not subsidizing the storage of someone else’s junk from 2021; you are only paying for the active state of the network today.

The Bridge to Web2 Adoption

The ultimate goal of any Web3 technology should be to replace the incumbent Web2 giants. We want decentralized alternatives to Amazon AWS, Google Cloud, and Azure. But to compete with them, we must match their feature set.

Amazon S3 (Simple Storage Service) is the backbone of the modern internet specifically because it is flexible. Developers can set lifecycle rules: "Store this log file for 30 days, then delete it." "Move this video to cold storage after a year." Walrus brings these capabilities to the blockchain world.

Because Walrus is programmable via the Sui blockchain, developers can automate these lifecycle decisions using smart contracts. A hospital could use Walrus to store patient records with a smart contract that automatically renews the storage for the legally required 7 years, and then allows it to expire. A news organization could archive raw footage for a decade before releasing the space.

This capability is what will convince the CTOs of major companies to make the switch. They can finally get the benefits of decentralization—security, no single point of failure, lower costs—without giving up the control they need to run their businesses responsibly.

Conclusion: A Mature Protocol for a Mature Industry

For a long time, the crypto industry has been dominated by idealism. We built things that were theoretically perfect but practically unusable. The concept of the "Permaweb" is one of those ideals—beautiful in principle, but flawed in practice.

Walrus represents the maturation of the industry. It admits that not everything needs to last forever. It acknowledges that laws exist. It recognizes that for a system to be sustainable, it must be able to clean itself up.

By offering a unique combination of decentralized security and mutable flexibility, Walrus is carving out a lane that no other protocol is occupying. It is building a hard drive that respects the user’s right to remember, but also their right to forget. In doing so, it is laying the groundwork for a decentralized web that is not just a rigid archive of the past, but a dynamic, living substrate for the future.