If you’ve spent time around real trading systems, one truth shows up fast: speed is valuable, but certainty is priceless. A market can tolerate a slow interface for a moment. It cannot tolerate settlement that might change after the fact. That’s why traditional finance treats final settlement like a sacred boundary—once the system says “done,” downstream risk models, accounting, compliance reporting, and custody all move forward assuming it’s irreversible. Many blockchains, especially the ones built for open participation and high throughput, grew up with a different culture: “it’s probably final after enough confirmations.” That logic works for some uses, but it clashes with regulated workflows where “probably” is a red flag.

Dusk’s architecture reads like it was designed around that friction. Instead of starting with a developer playground and later adding a settlement story, it starts by emphasizing fast, deterministic finality at the base layer. The philosophy is simple: if you want to host financial markets—especially those that care about privacy and compliance—your settlement layer has to behave like infrastructure, not like a chat timeline where history can be rearranged.

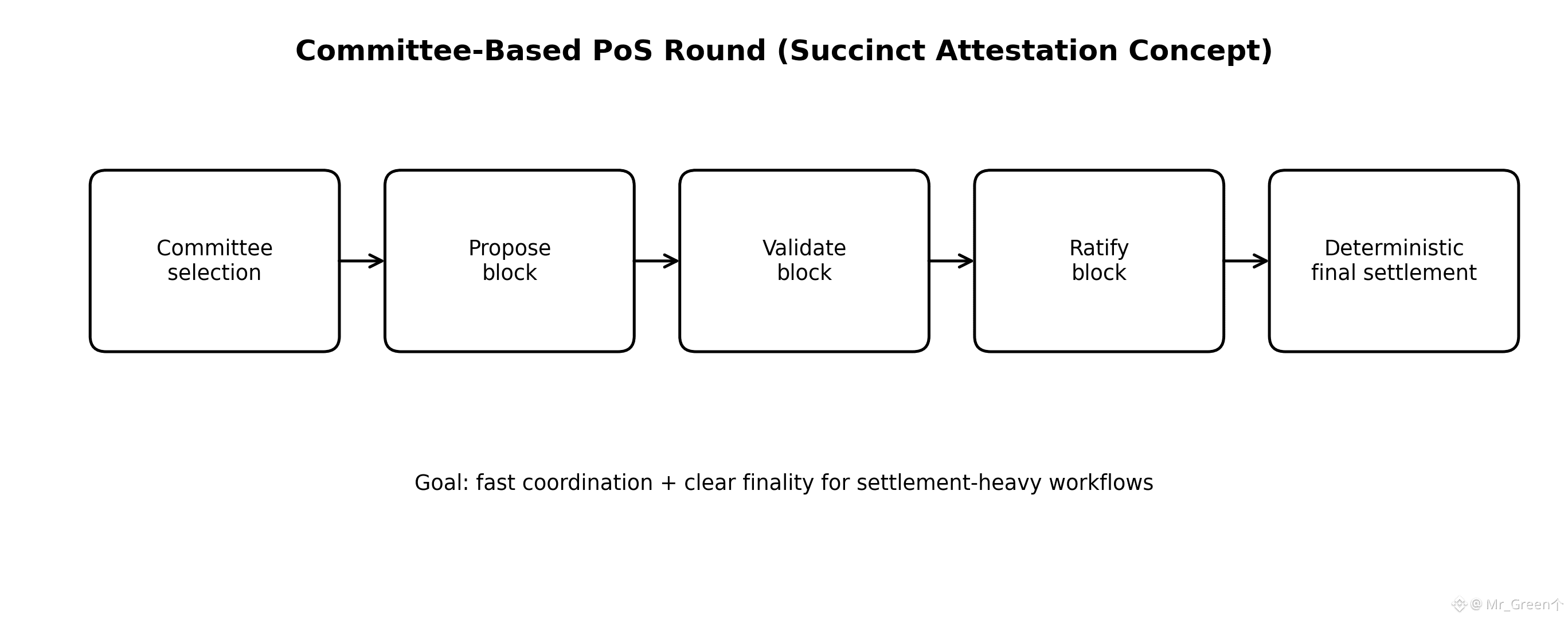

The technical center of that approach is Dusk’s proof-of-stake consensus protocol, Succinct Attestation, which leans on committee-based participation. The key idea behind committees is not new, but the motivation is very finance-native: you want decisions to be made quickly by a subset of participants, without forcing the entire validator set into heavy coordination every block. In a large validator network, full participation in every step can become a latency tax. Committees reduce that overhead. If committee selection is robust and unpredictable, you get a system that can move fast while still being protected by the broader economic security of staked participants.

This is where the interesting tradeoffs live. Committees only work if the selection process is strong enough to resist capture. If an attacker can predict or influence committee membership, they can concentrate power at the exact moment it matters. So the design needs randomness that is credible, stake-weighting that is fair, and rules that prevent “committee gaming.” On the other side, committees need to stay small enough to be fast—but not so small that collusion becomes cheap. That sizing problem is not cosmetic. It’s the difference between “market-grade finality” and “finality that looks good until the first stress event.”

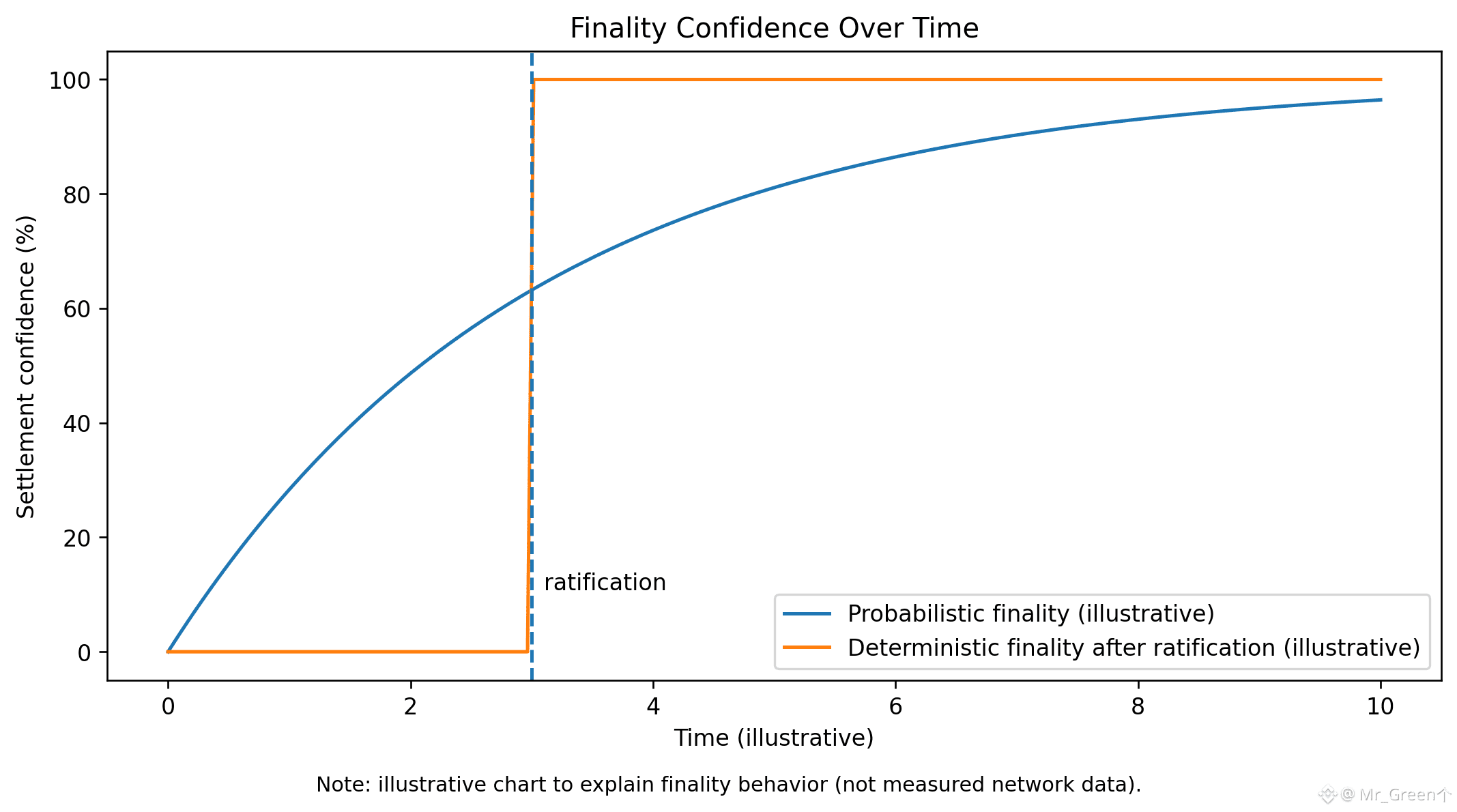

Finality itself is the second big tension. Deterministic finality makes settlement feel clean: when a block is ratified, it’s final in normal operation. That is extremely appealing for trading, clearing, and custody processes, because it simplifies everything around it. But you pay for deterministic claims with stricter safety requirements. The system must be engineered so that conflicting blocks can’t both be ratified. That pushes you toward careful protocol rules, strong assumptions about honest stake, and enforcement mechanisms that punish misbehavior. In proof-of-stake systems, incentives are not a side story. They’re the lock on the door. If finality is fast, the deterrent must be real enough that rational actors don’t even try to violate it.

Liveness is the third pressure point. Finance doesn’t just need final settlement; it needs settlement that continues under stress. Committee systems can be fast when the network is healthy, but markets don’t pause because a subset of participants is offline. So the protocol has to handle slow members, missing signatures, and partial outages without stalling. This is the less glamorous part of consensus design, but it’s the part that determines whether “finality-first” is a slogan or a property that holds on bad days.

When you connect these choices back to Dusk’s broader narrative—privacy plus regulation—the focus on finality starts to look less like branding and more like dependency management. Privacy systems (especially confidential transaction models) often add complexity: proofs, verification steps, and special handling of state transitions. Compliance workflows add constraints: eligibility checks, controlled disclosure, audit access paths. Those layers only make sense if the base system can settle outcomes cleanly. A regulated institution doesn’t want to build reporting on top of a ledger that might rewrite its last page. Dusk’s bet is that a settlement layer designed for deterministic finality can act like the stable ground that privacy and compliance tools can safely stand on.

That’s why “Finality First” is more than a performance claim. It’s a design stance. Dusk is trying to make the base layer behave like a market utility: quick decisions, clear outcomes, and a chain of custody for state that’s hard to dispute. The real test will always be in execution—how the committee selection holds up, how incentives shape behavior, how the network performs under adversarial pressure. But the framing is coherent: if you want to replace opaque, centralized settlement rails with something verifiable, you can’t replace them with uncertainty. You replace them with quiet certainty—final settlement that arrives fast, stays final, and is reliable enough that regulated systems can treat it as real.