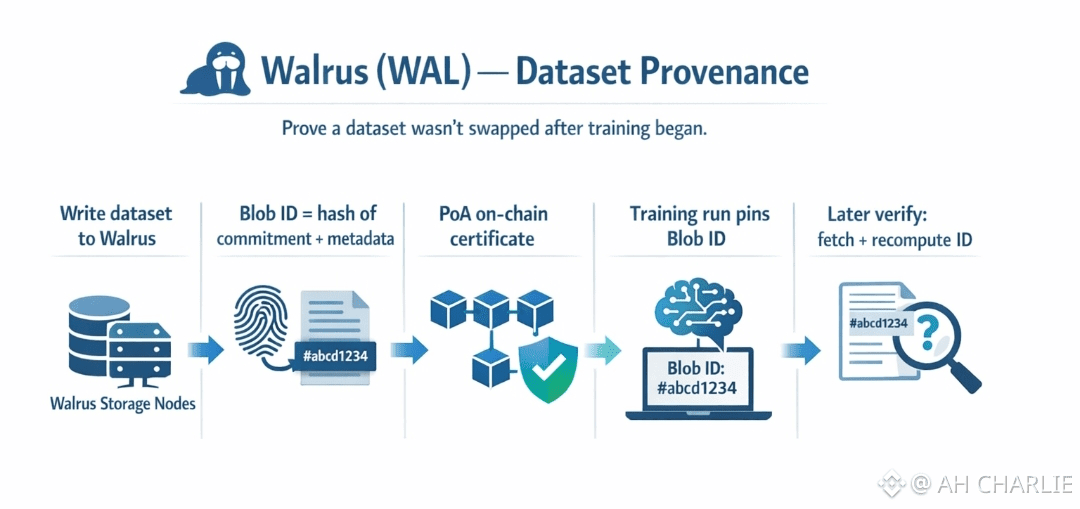

You know that uneasy feeling when a model starts doing “too well”… and someone quietly asks, “Wait. Are we sure it trained on that dataset?” Not because the data was bad. Because the data could’ve been swapped mid-run, and nobody would notice until it’s too late. That’s the messy new kind of trust problem in AI: not just what you trained on, but whether it stayed the same after training began. Walrus actually calls this out as a core use case in the age of AI - making sure training sets are not manipulated or polluted, and keeping real trace back to what was used. Walrus attacks the “swap” problem with something that feels almost boring. A strong fingerprint, plus a public record, plus a way to re-check later. When you write data to Walrus, you don’t just upload a file. The writer encodes the blob, gets commitments (think “sealed promises” about each piece), and creates a blob commitment. Then the blob id is derived by hashing that commitment together with basic facts like file length and encoding type. In plain words: change the data, and the id changes. There’s no “same id, new content” trick if the hash is solid. Walrus leans on standard crypto ideas here: a collision-resistant hash (a hard-to-fake fingerprint) and binding commitments (a promise you can’t rewrite later). And it’s not floating in the air. Walrus uses a blockchain control plane (the paper describes using Sui) to register the blob and its metadata, so the id and commitment become part of an on-chain trail. Now the part that matters for provenance: the Point of Availability, or PoA. The writer collects enough signed acknowledgments from storage nodes to form a write certificate, then publishes that certificate on-chain. That on-chain publish is the PoA. From that moment, the network has an explicit duty to keep the blob available for reads during the paid period, and the PoA itself can be shown to third parties and smart contracts as proof the blob became available under Walrus rules. So you get a public “this exact blob id entered the system properly” moment. If your training run claims “I used blob id X,” you can point to the PoA record for X. If someone tries to swap in dataset Y, they don’t get to keep id X. They have to mint a new id. And that mismatch is the whole point. Okay, but what about a sneakier attack: keep the id, mess with the pieces. This is where Walrus is strict in a very practical way. Reads are not “trust the node.” A reader asks for slivers plus proofs, checks them against the commitments, rebuilds the blob, then re-encodes and recomputes a blob id. If the recomputed id matches the blob id you asked for, you accept the blob. If not, you output failure. That means the verification is end-to-end. The data either matches the id, or it doesn’t. No vibes, no “close enough.” And if a malicious writer tried to upload slivers that don’t even match a correct encoding, Walrus is designed so the system can produce a third-party verifiable proof of inconsistency, and nodes can even attest on-chain that the blob id is invalid after enough attestations. So “silent corruption” has a hard time staying silent. So how do you prove “wasn’t swapped after training began” in a way normal people can audit? You anchor the training run to the blob id, and you treat the blob id like a dataset commit in git. Before training starts, record the blob id in whatever log you expect others to trust: an on-chain note, a signed run manifest, a public report, even a simple attestation. Then, whenever someone wants to verify, they fetch the blob by that id, run the Walrus read path, and confirm the id recomputes cleanly. If the training team later tries to “upgrade” the dataset quietly, the new dataset will have a new id. That’s not a moral claim. It’s just math. There’s also a subtle upgrade here: durability of the evidence. The whitepaper talks about blobs being marked non-deletable, and how anyone can convince a third party of availability by proving a certified blob event was emitted on Sui with the blob id and remaining epochs. It even notes you can verify those events with a light client, without running a full node. Translate that into provenance language and it’s pretty clean: you’re not asking auditors to trust your server, or trust your team, or trust your cloud bucket naming scheme. You’re giving them an external, verifiable event tied to the blob id, plus a way to re-check the bytes later. One more human truth, though. Walrus can prove the dataset wasn’t swapped after you locked in a blob id. It can’t magically prove the dataset was “good” or “fair.” It proves sameness and traceability. That’s still huge. Because once you can’t swap quietly, you can start having honest talks about what went in, what came out, and who signed off. Not Financial Advice. And if you want a simple mental image to remember it: Walrus turns a dataset into a sealed jar with a label you can’t copy. Training begins with the label written down in public. Later, anyone can open the jar and check the seal still matches the label. If someone hands you a different jar, you’ll see it fast.

@Walrus 🦭/acc #Walrus $WAL #Sui #Web3