I've been looking at who actually controls stake distribution on Walrus and it's not what most people assume. WAL trades at $0.1259, down 2.10% with volume hitting 7.41 million tokens today. RSI at 33.99 shows some recovery from oversold levels. But the interesting story isn't price—it's who decides which storage nodes succeed and which fail.

Everyone talks about the 105 operators running Walrus infrastructure. They're visible, they run hardware, they show up in dashboards. But they're not really where power sits.

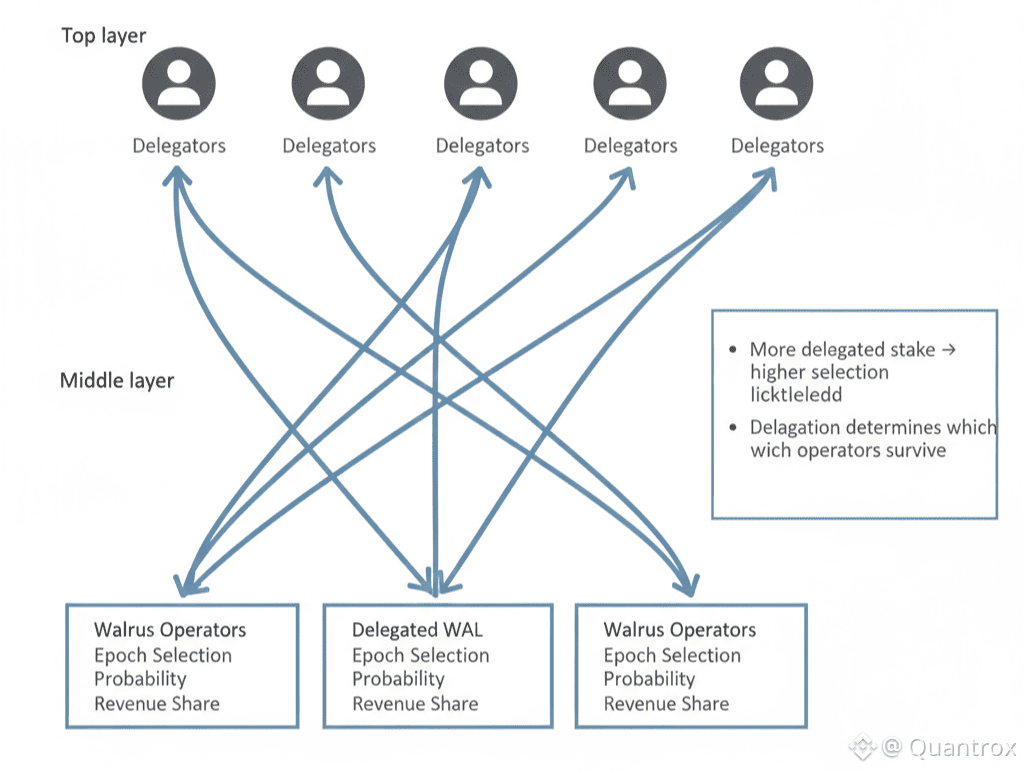

Delegators are. The token holders who stake their WAL with specific operators determine everything about network dynamics. Which nodes get selected each epoch. Which operators earn meaningful revenue. Which infrastructure investments pay off. All decided by delegation choices that happen mostly invisibly.

Here's what caught my attention. Walrus uses delegated proof of stake. Operators need WAL stake to participate, but they don't have to provide all of it themselves. Token holders can delegate their WAL to operators and earn a share of fees. Standard DPoS setup. But the implications go deeper than most projects.

An operator with great hardware but little delegated stake doesn't get selected. An operator with decent hardware but strong delegation dominates. The technical quality of storage infrastructure matters less than the ability to attract stake. That creates weird incentives.

Operators have to market themselves. Convince delegators they're reliable. Offer competitive commission rates. Build reputation. Maintain social presence. All the soft skills that have nothing to do with running storage nodes well. If you're technically excellent but bad at attracting delegation, you lose to operators who are technically adequate but good at marketing.

That's not necessarily bad. Delegators need information to make choices. Operators providing transparency about uptime, commission rates, infrastructure quality—that's valuable. But it also means Walrus success depends as much on social coordination as technical execution.

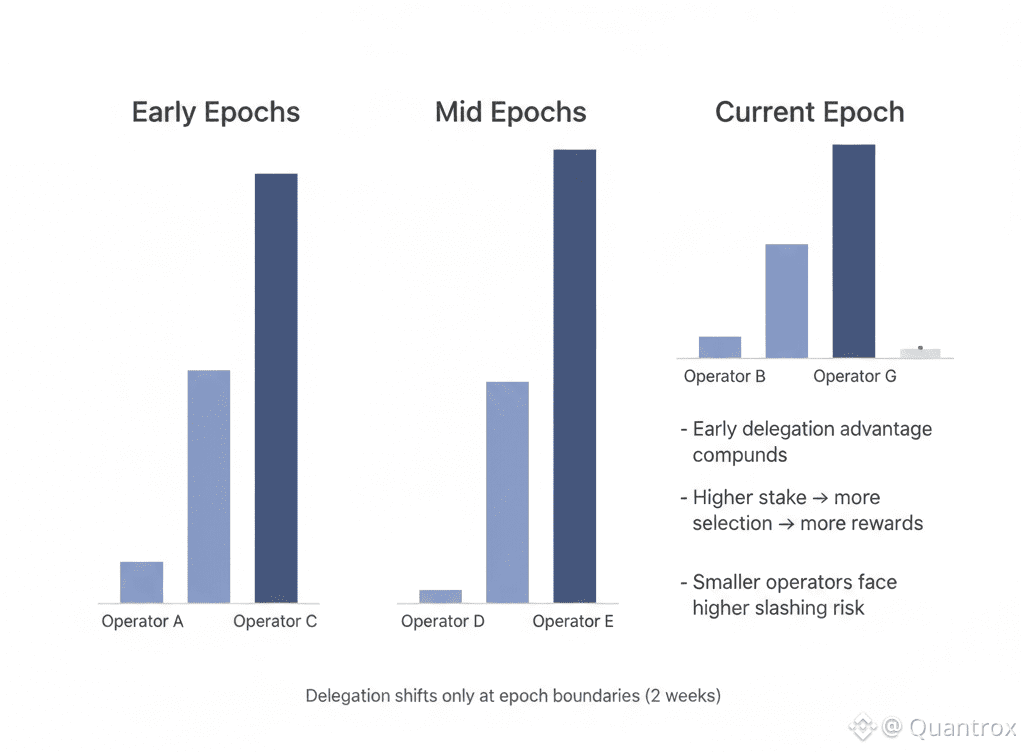

The 105 operators across 17 countries are competing for finite delegation. Every epoch, the protocol looks at stake amounts and selects nodes accordingly. More stake means more selection means more revenue means more ability to expand infrastructure. It's self-reinforcing. Operators who get early delegation have advantages that compound over time.

Which means early delegators have outsized influence. The token holders who chose operators during testnet or early mainnet shaped which nodes dominate now. Their delegation decisions created the power structure that exists today. Later delegators are mostly choosing from already-successful operators rather than discovering new ones.

Volume of 7.41 million WAL today includes some delegation activity that doesn't show up separately in trading metrics. When someone delegates tokens, WAL moves on-chain but might not hit exchanges. The actual economic activity around delegation is harder to track than simple trading volume.

Walrus burns some WAL through slashing when operators fail availability checks. But operators with strong delegation can absorb slashing events better than those barely maintaining minimum stake. One slashing penalty might kill a small operator while a well-delegated one barely notices. That makes the system less forgiving to newcomers.

The circulating supply of 1.58 billion WAL out of 5 billion max means most tokens that could be delegated aren't yet. As more unlocks, delegation competition intensifies. Operators need to continuously attract new stake as supply grows or they fall behind in relative terms even if their absolute stake stays constant.

Here's where it gets complicated. Delegators want maximum returns, which means choosing operators with high uptime and low commission rates. But they also want network decentralization, which means spreading stake across many operators instead of concentrating on the top few. Those goals conflict.

If every delegator optimizes for personal returns, stake concentrates on the best operators. Network becomes more centralized even though it's technically decentralized infrastructure. If delegators prioritize decentralization, they accept lower returns by supporting smaller operators. Most will optimize for returns. That's just rational behavior.

Walrus doesn't force delegation diversity. The protocol lets stake concentrate wherever delegators choose. Some DPoS networks cap how much stake one operator can have or implement other mechanisms to enforce distribution. Walrus leaves it to market dynamics. Maybe that works long-term. Maybe it leads to concentration that defeats the decentralization purpose.

My gut says most delegators don't think about network-level effects. They're just optimizing their own position. Pick the operator with the best risk-adjusted returns, delegate, collect rewards. Multiply that across thousands of delegators and you get emergent centralization even if nobody intended it.

An RSI around 34 hints that WAL may be climbing out of oversold territory. If price starts to recover, delegation naturally looks more appealing. A higher token price means rewards are worth more in fiat terms. That could pull in new delegators and spread stake out, or do the opposite—push big holders to double down and concentrate it even more.

Operators running Walrus nodes are building long-term infrastructure. But their viability depends entirely on attracting and retaining delegation. Technical excellence is necessary but not sufficient. Social reputation, marketing, commission competitiveness—all matter as much as uptime and reliability.

That makes Walrus more political than most realize. It's not just technical infrastructure. At its core, it’s a coordination game. Operators compete for delegation, delegators decide with partial information, and incentives aren’t perfectly aligned. The protocol sets the rules, but the real outcome depends on how people collectively behave.

Epochs lasting two weeks create natural checkpoints where delegation can shift. Unhappy with an operator? Wait until epoch boundary and redelegate. But moving stake has costs—you might miss rewards during transition, might pick a worse operator, might trigger other consequences. So delegation tends to be sticky even when better options exist.

The way storage pricing works adds a subtle layer to delegation decisions. Since operators vote on costs every epoch, you’re not just choosing uptime or reputation anymore. Some operators may push prices lower to pull in more usage, while others will prioritize margins. Where you delegate starts to shape the economics you’re exposed to. Others might vote high to maximize revenue per terabyte. Delegators need to understand their operator's pricing philosophy because it affects fee generation.

Walrus processed over 12 terabytes during testnet. That testing phase let delegators evaluate operators before real value was at stake. The delegation patterns established during testnet carried into mainnet. Early reputation from testnet performance still matters now, months later. First impressions last.

What you'd want to know as a delegator is not just current uptime but consistency over time, slashing history, commission rate trends, operator communication quality, infrastructure investment patterns. Most of that information is scattered or unavailable. Delegation becomes as much gut feel as data-driven decision.

Maybe mature Walrus has robust delegation markets where information is better and choices are clearer. Or maybe information asymmetry persists and delegation concentrates around operators who are best at marketing rather than best at operations. We're early enough that either outcome is plausible.

Time will tell whether Walrus delegation dynamics lead to healthy distributed stake or concentration that undermines decentralization. For now delegators hold more power than the 105 operator number suggests. They decide winners and losers every epoch through choices most people never see.