I've been trying to understand how Walrus actually verifies that storage nodes are holding data they claim to store and the answer is more interesting than expected. WAL sits at $0.1259 today with volume at 7.41 million tokens, RSI climbing to 33.99 from deeper oversold levels. Price action gets attention but the verification mechanisms underneath might matter more long-term.

Most people assume decentralized storage just works. You upload data, it gets stored, you can retrieve it later. Simple. But how do you know nodes are actually storing your data instead of deleting it and gambling they won't get caught?

That's the data availability problem. And Walrus had to solve it properly or the entire economic model breaks.

Traditional cloud storage doesn't have this problem because you trust the provider. AWS says they're storing your data, you believe them. Maybe they show you metrics. But fundamentally it's trust-based. Walrus can't work that way. The whole point is not depending on centralized trust.

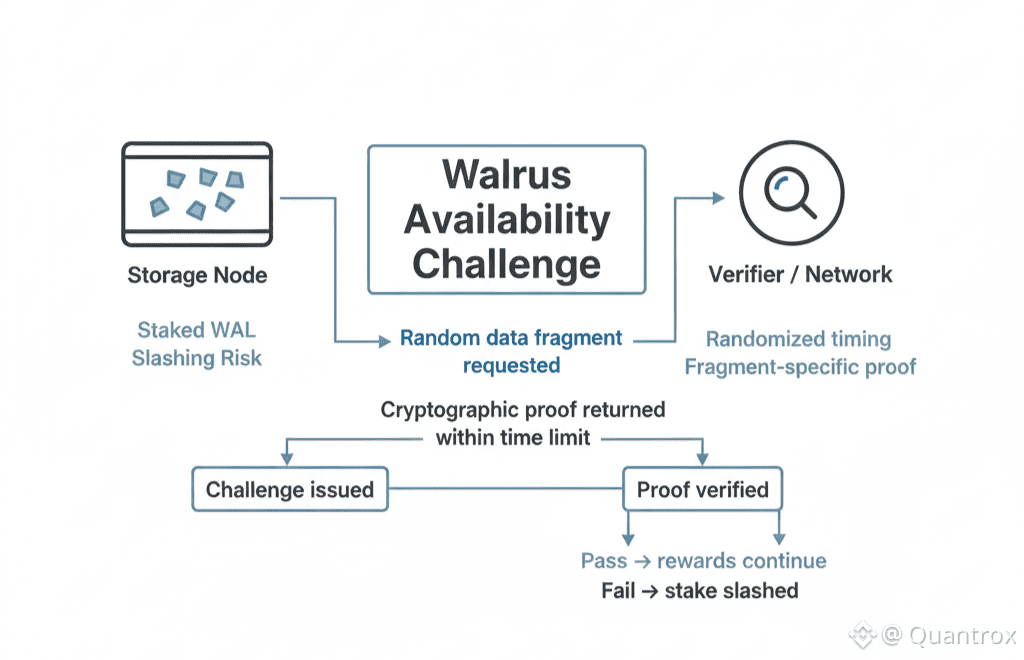

Here's what caught my attention. Walrus uses availability challenges. Randomly selected nodes get asked to prove they're holding specific data fragments at specific times. They have to respond with cryptographic proofs within a time limit. Fail the challenge and you get slashed. Miss enough challenges and you're out.

That sounds straightforward until you think about the attack vectors. What if a node stores some data but not all of it, gambling they won't get challenged on the missing pieces? What if multiple nodes collude to cover for each other? What if someone figures out how to fake proofs without actually storing data?

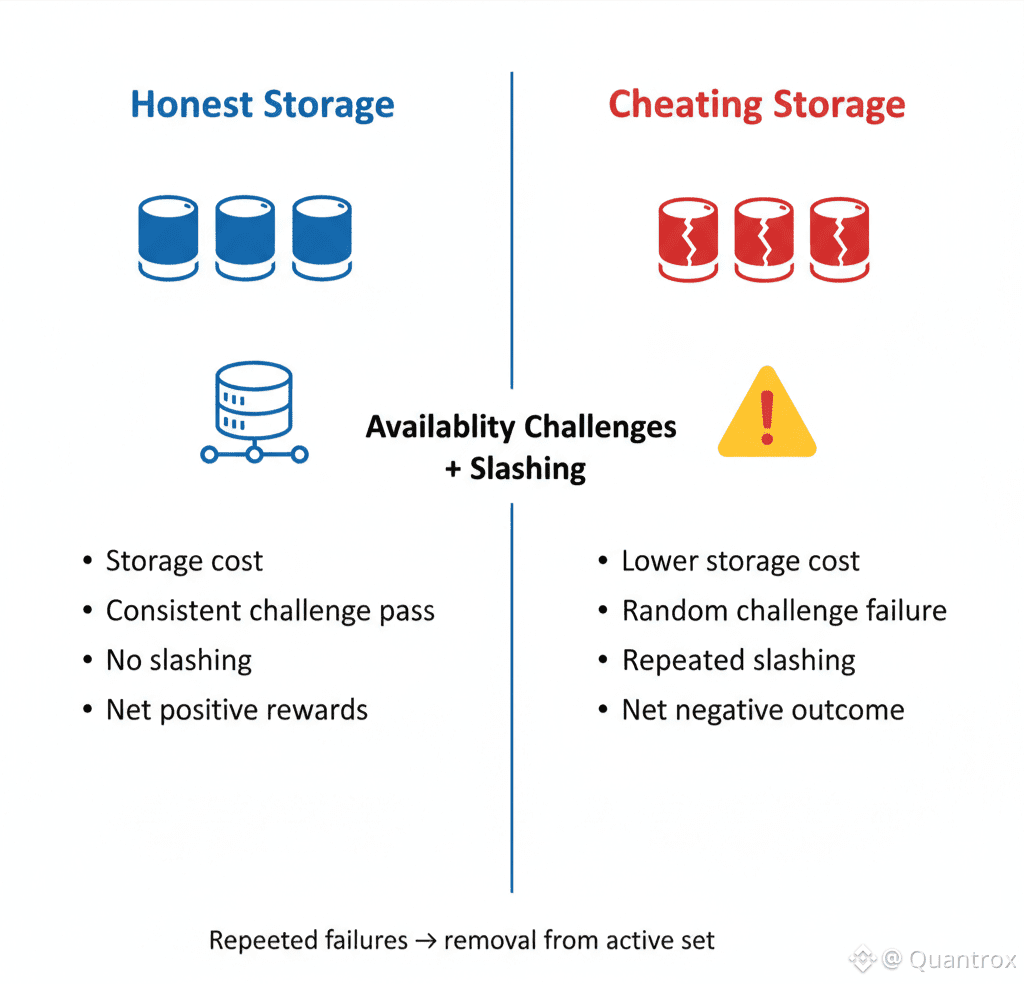

Walrus had to design challenge mechanisms that make all of those attacks economically irrational. The math has to work out so that actually storing data is cheaper than trying to cheat the verification system. Get that wrong and the network slowly fills with nodes pretending to store data they've deleted.

The Red Stuff encoding helps here. Two-dimensional erasure coding means data gets split into fragments distributed across many nodes. Any single node only holds pieces, not complete files. To reconstruct data, you need fragments from multiple nodes. That makes collusion harder—more parties have to coordinate to successfully fake storage.

Storage nodes on Walrus stake WAL tokens. That stake is what gets slashed if they fail availability challenges. The economic game theory says that if storing data costs less than the expected value of slashing penalties for failing challenges, rational operators will just store the data properly.

But here's where it gets tricky. Slashing penalties need to be high enough to discourage cheating but not so high that honest operators who have temporary technical failures get destroyed. Random hardware failures happen. Network issues happen. Power outages happen. The protocol needs to distinguish between malicious behavior and bad luck.

Walrus handles this through repeated challenges over time. One failed challenge might be bad luck. Pattern of failures suggests actual problem. The slashing mechanics scale based on failure frequency. Small mistakes get small penalties. Persistent failures get increasingly harsh treatment until the operator is eventually removed from the network.

The 105 operators running Walrus infrastructure are all subject to these challenges continuously. Every epoch, challenges get distributed randomly. No one knows when they'll be challenged or which data fragments they'll need to prove they're storing. That unpredictability is important—if challenges were predictable, nodes could store only the data likely to be challenged and delete everything else.

Volume of 7.41 million WAL includes the token movements from slashing events, though they're not separately visible in trading metrics. When nodes fail challenges and lose stake, those tokens don't just disappear—some get burned, some get redistributed. That happens continuously as part of normal network operations.

The availability challenge system creates ongoing costs for nodes. They need fast storage, good network connectivity, robust infrastructure. Slow disk access means failed challenges. Unreliable networking means failed challenges. Cutting corners on hardware means slashing penalties. The protocol forces infrastructure quality through economic pressure.

That's different from traditional cloud where the provider has reputation to maintain but individual servers can be marginal. One bad AWS server doesn't matter much to Amazon's reputation. One bad Walrus node means slashing penalties that directly hit that operator's economics. The incentive structure is more granular and immediate.

My gut says this verification layer is both Walrus's strength and potential weakness. Strength because it creates trust-minimized data availability. You don't have to trust nodes are storing data—you can verify through cryptographic proofs. Weakness because the challenge system adds complexity and cost that centralized storage doesn't have.

The protocol doesn't care whether WAL is $0.12 or $1.20. Challenges happen on schedule, nodes respond or get slashed, data availability gets verified. Market sentiment doesn't affect infrastructure requirements.

Epochs lasting two weeks create natural boundaries for assessing availability patterns. Over one epoch, you can see which operators consistently pass challenges and which struggle. That information helps delegators make staking decisions. Operators with perfect challenge records attract more delegation. Operators with frequent failures lose stake.

The pricing mechanism where operators vote on storage costs every epoch interacts with availability requirements. Operators voting for higher prices need to justify it with better reliability. Cheap storage from nodes that frequently fail challenges isn't actually cheap—it's expensive data loss risk. The market should theoretically price in reliability based on challenge history.

Walrus processed over 12 terabytes during testnet specifically to stress-test availability challenge mechanisms. Did they scale? Could the network handle challenge verification at real usage levels? Were slashing penalties calibrated correctly? Testnet answered those questions before actual value was at stake.

What you'd want to know as someone storing data on Walrus is not just that availability challenges exist but how often they happen, what the success rate is across the network, how quickly failed nodes get removed. Those metrics determine actual data durability in practice versus theory.

The 17 countries where Walrus nodes operate create geographic diversity that affects availability. Nodes in different regions face different network conditions, power infrastructure, regulatory environments. A challenge response that's easy in low-latency regions might be harder in areas with poor connectivity. The protocol has to account for that without making it easy to cheat by claiming poor infrastructure.

Operators running Walrus storage aren't just hosting data—they're participating in continuous cryptographic verification games where failure means financial penalties. That's fundamentally different from centralized cloud where infrastructure failures are internal problems that don't directly hit individual server operators financially.

The burn mechanics from slashing mean Walrus availability challenges contribute to deflationary pressure. Every failed challenge burns some WAL. The better the network performs, the less burning happens from slashing. The worse nodes perform, the more tokens get destroyed. Network quality and tokenomics are directly linked.

Whether this availability proof system is overkill or essential depends on your use case. Applications that need absolute guarantees of data durability probably care about these verification mechanics. Applications that just want cheap storage might not value the added assurance enough to justify the complexity.

Time will tell if Walrus availability challenges become the standard for decentralized storage verification or if simpler trust-based models win through convenience. For now it exists, works continuously, and makes Walrus fundamentally different from just "decentralized AWS" even if that difference is invisible to end users.