Most analysis still treats Walrus as a straightforward attempt to make decentralized storage cheaper, faster, and easier. That framing misses what is actually novel about the system. Walrus is architected so that “storage” is not merely a service you buy. It becomes a programmable, ownable resource with explicit lifetimes, explicit proof artifacts, and an incentive system that can be tuned without rebuilding a whole new base chain. The reason this matters now is that the next wave of onchain applications is running into a constraint that is not about execution throughput. It is about who can credibly promise custody of large blobs, under churn, with predictable costs, and with a verification surface that is legible to both smart contracts and institutions. Walrus is one of the first designs that tries to make that promise mechanically enforceable while keeping the data plane specialized and the control plane general-purpose, via Sui.

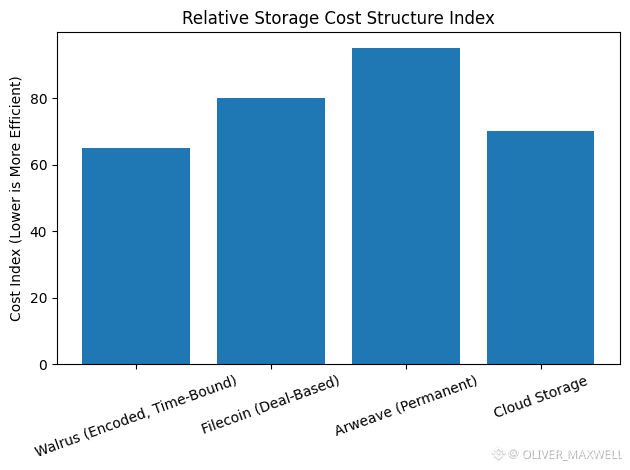

Walrus differs from Filecoin, Arweave, and cloud storage in a way that is more structural than feature-level. Cloud providers like S3 optimize for operational guarantees backed by a single operator, where durability is engineered through internal replication across availability zones and expressed as a service property, not a publicly auditable state transition. Walrus is doing almost the opposite. It tries to externalize the custody guarantee into a public onchain artifact and then make the network economically punishable when reality diverges from that artifact. In Filecoin, the core custody guarantee is expressed through proof systems and then operationalized through storage and retrieval deals that live inside Filecoin’s own market structure. In Arweave, the economic promise is permanence, where users effectively pay once and the protocol relies on an endowment-style model to sustain long-lived storage incentives. Walrus is neither a permanence protocol nor a pure storage deal marketplace. Its defining choice is to treat blob custody as an epoch-based, committee-coordinated service whose “truth” is anchored to Sui objects and Sui transactions. That makes Walrus less like a decentralized hard drive and more like an auditable custody schedule for data, where the schedule is programmable because the storage resource itself is an onchain object.

The architectural consequence is that Walrus can optimize aggressively for blob workloads without inheriting the complexity and governance surface of running a full standalone L1 for everything. Walrus explicitly separates the data plane from the control plane, with Sui handling payments, metadata, shard assignment, and lifecycle orchestration. This is not just an implementation preference. It changes the competitive frontier. If you believe the hardest part of decentralized storage is “how do we store bytes cheaply,” then all protocols converge toward better erasure coding and better bandwidth economics. If you believe the hardest part is “how do we coordinate custody under churn and make that coordination composable with applications,” then Walrus’s Sui-native object model becomes a differentiator that is difficult to replicate without an equivalent execution layer that treats objects, ownership, and lifecycle as first-class. Walrus literally binds blobs to Sui objects and uses Sui to track owners and lifetimes.

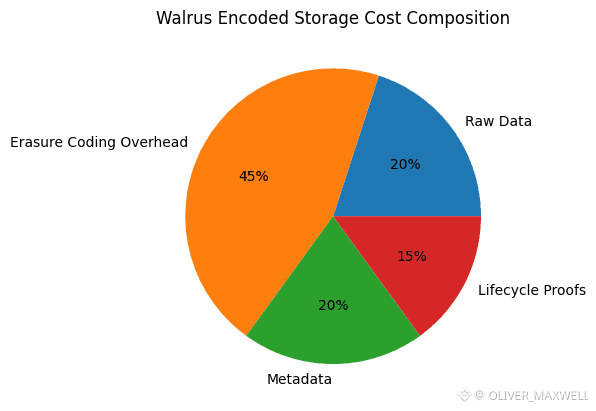

Where that becomes concrete is in Walrus’s core storage representation and cost mechanics. The cost basis is not the raw file size you upload. The system charges and provisions based on encoded size, which is roughly five times the original blob size plus a fixed per-blob metadata overhead that can be large, meaning small blobs can be disproportionately expensive if you treat Walrus like a generic key-value store for tiny objects. This one detail explains why Walrus is not trying to compete with every storage protocol everywhere. It is tuned for large, binary objects where you can amortize metadata and exploit the efficiency of erasure coding at scale, and it openly provides a batching tool to reduce the small-blob cost penalty by amortizing metadata across many items. The competitive implication is that Walrus’s “cheaper storage” narrative is only true in the workload regimes it was designed for. If your competitor comparison assumes lots of sub-megabyte objects, you are benchmarking Walrus on a non-native workload and the economics will look worse than they need to.

This design shows up again in performance characteristics that many creators ignore because it does not fit the usual decentralized storage storyline. In Walrus’s own evaluation, read latency for smaller blobs stays relatively low, while write latency reflects a meaningful fixed overhead from metadata handling and blockchain publication. What is interesting is not the raw numbers. It is the breakdown. A significant portion of write latency comes from publishing custody and verification information onchain. That is the signature of a system where your “storage write” is not just uploading bytes. It is also buying a lifecycle resource and publishing a proof artifact that can be referenced later. This is the hidden trade. Walrus is pricing in auditability and composability upfront, so it will never behave like a pure CDN upload endpoint for tiny assets, and it does not need to.

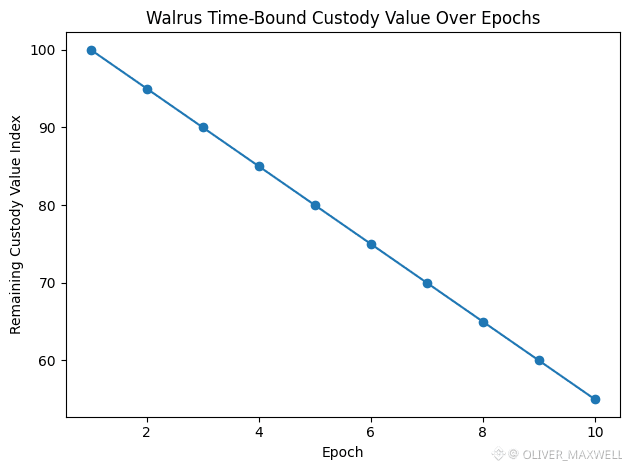

If you follow that thread into incentives, you see why Walrus may end up with a different equilibrium than Filecoin-like markets. Walrus storage is purchased for a fixed duration measured in epochs. Storage can be bought up to a bounded maximum, which is effectively a forward contract on custody rather than an unbounded permanence promise. This matters because it makes storage pricing a time-structured market. The protocol can aim to keep storage costs stable in fiat terms and protect against long-term WAL price fluctuations, and it explicitly describes a mechanism where users pay upfront and payments are distributed across time to nodes and stakers as compensation for ongoing service. When you internalize that, WAL stops looking like a simple utility token and starts looking like the unit of account for a time-based custody budget, with the protocol acting as the scheduler that releases that budget across the custody period. That is closer to an annuity-like payout stream than to a one-time fee model.

This also explains why Walrus couples delegated staking to data assignment. Storage nodes must stake WAL to participate, and delegated staking determines which nodes receive assignments and thus revenue, aligning stake-weighted security with operational responsibility. If you are an experienced trader, the interesting question is not just “what is staking yield.” The question is what variables drive the yield curve. Walrus itself emphasizes that rewards start low and scale as the network grows, which is a polite way of saying early yields are not meant to subsidize speculation indefinitely. They are meant to be a function of real storage demand and protocol-set parameters. So the long-term bull case for WAL staking is not a high APR headline. It is that Walrus succeeds at making storage demand predictable enough that a meaningful share of custody payments flows to stakers and operators, while governance tunes penalties and migration costs so that operator quality stays high. That is a harder equilibrium to reach than “emit more tokens.”

The most underappreciated economic lever in Walrus is its explicit acknowledgement that churn creates externalities. When stake shifts, data must migrate, and migration is not free. Walrus calls this out directly by proposing a penalty fee on short-term stake shifts that is partially burned and partially distributed to long-term stakers, precisely to discourage noisy reallocations that impose migration costs on the network. This is a very specific piece of mechanism design that most storage protocols do not attempt. It is effectively saying that liquidity in staking choice is not purely beneficial, because the network’s physical reality, even with erasure coding, has a migration bill. If this mechanism is executed well, it can produce a market where stake is stickier around operationally competent nodes, which improves reliability. If it is executed poorly, it can entrench incumbents and reduce competitive pressure on operators. Either way, it is a core differentiator because it makes Walrus governance a first-order variable in network quality, not an afterthought.

Privacy is another area where a lot of coverage gets sloppy, and the official design is more precise than most commentary. Walrus does not provide native encryption for data. By default, all blobs are public and discoverable, and if you need confidentiality you must secure data before uploading. This matters because it means Walrus’s base layer is optimized for availability and integrity, not secrecy. The privacy story is implemented as an overlay, and Walrus explicitly recommends a threshold-encryption based access control system for onchain policy enforcement. The trade-off is clear. You gain composable access control that can be enforced by smart contracts, but you are now operating a key management and policy system on top of storage, which introduces its own complexity and performance costs. The upside is that Walrus does not have to contort its base storage protocol around confidentiality, and can keep the data plane simple and scalable while letting the privacy layer evolve faster.

This layered approach also reveals a strategic bet: Walrus is positioning itself as infrastructure for programmable data, not just decentralized storage. The proof-of-availability model illustrates this. Walrus’s write flow produces an onchain proof artifact that serves as a public record of custody, created after encoding, distributing slivers, collecting node acknowledgements, and publishing a certificate to the Walrus smart contract on Sui. The important point for institutional readers is auditability. If your compliance team asks, “can we prove the data existed, and can we prove it was held under an explicit service agreement for a defined period,” Walrus is designed to answer that with an onchain trail, rather than with a vendor attestation. That is a qualitatively different offering than most decentralized storage systems that focus on cheap capacity and assume the application will figure out verification later.

Institutions, however, do not adopt storage because a proof exists. They adopt when the integration surface fits procurement reality. Walrus’s strongest institutional angle is not decentralization as ideology. It is controllability of lifecycle and cost predictability. Storage is purchased for a defined number of epochs, the network parameters define epoch duration and maximum epochs available, and costs can be measured directly through onchain transactions. Walrus even distinguishes between costs that scale with encoded size and duration and gas costs that are independent of blob size. That separation is exactly the kind of detail enterprises care about because it lets them model operating cost drivers and isolate them. The uncomfortable caveat is that the most visible, canonical evidence of enterprise deployments is still limited in public view. What is more evident is ecosystem integration through infrastructure providers and applications that behave like real products rather than demos. That is a credible signal that Walrus is being treated as a production substrate by teams that care about user experience and reliability.

On the application side, the highest-signal use cases for Walrus are the ones that exploit two properties simultaneously: large blobs and onchain programmability of the blob’s lifecycle and access. Hosting and content delivery are obvious examples, but the more strategically important class is data products, where the blob is not just content but an asset whose access rights can be sold, delegated, or conditioned on other onchain states. This is where access control becomes the connective tissue. Data marketplaces, token-gated subscriptions, dynamic gaming content, and enterprise content rights management all fall into this category. If Walrus wins anywhere, it is likely in these policy-heavy regimes where cloud storage is technically capable but institutionally contentious because of platform risk, and where other decentralized storage protocols either do not offer access control primitives or force every builder to reinvent them.

Network health and tokenomic sustainability are harder to evaluate cleanly from the outside because some metrics are not always easily observable. What can be assessed is the shape of the system and what it implies about sustainability. Walrus Mainnet is operated by a decentralized set of storage nodes, and governance processes around upgrades are structured so that votes complete within defined epochs and operators explicitly verify upgrade artifacts before approving them. That is not a cosmetic governance system. It is an operational governance system, and it indicates Walrus expects parameter tuning and contract upgrades to be routine. The WAL token model explicitly allocates supply for early adoption subsidies, acknowledging that early storage economics may be partially engineered to bootstrap usage. For investors, this means early pricing signals are not purely market-driven. The real question is whether subsidies buy durable developer lock-in and real workloads, or whether they simply buy temporary volume that fades.

There is also a more subtle sustainability question that is being underestimated. Walrus’s encoded size overhead and per-blob metadata costs create a system where the most value-dense use cases are not “store everything forever.” They are “store large objects when the onchain programmability of custody and access is worth the overhead.” That is good news for sustainability because it narrows the market to higher willingness-to-pay workloads rather than competing head-on with commodity cloud storage. It is also a risk because it means Walrus’s addressable market is not all storage. It is storage that wants to be an onchain object. If Sui’s application ecosystem grows in a way that makes that primitive indispensable, Walrus becomes infrastructure. If Sui’s growth skews toward applications that can tolerate offchain storage with weaker composability, Walrus may remain a niche, even if technically excellent.

This is where Sui integration becomes the central strategic variable. Walrus’s architecture assumes that Sui can be a high-throughput coordination layer that can manage payments, shard assignment, and metadata in a way that feels cheap and frictionless to developers. Walrus explicitly positions storage resources and blobs as objects on Sui, which means storage can be owned, transferred, and integrated into smart contract logic without inventing a parallel ownership system. Competitors can attempt to emulate programmable storage by building their own metadata chains or adding control layers, but that is not the same as having the control plane be a widely used execution environment with its own DeFi, identity, and application stack. The flip side is dependency risk. If Sui experiences congestion, governance turmoil, or a slowdown in adoption, Walrus inherits those constraints because its control plane is not optional. That is both a moat and a single point of strategic exposure.

Looking forward, Walrus’s most plausible adoption catalysts come from reinforcing trends rather than a single killer app. One is the normalization of data access control as an onchain primitive, where threshold encryption and policy-based decryption make data sharing monetizable without trusting a centralized gatekeeper. Another is the evolution of proof-of-availability and audit tooling into something compliance teams can understand and rely on. A third is the maturation of developer tooling that hides protocol complexity and presents Walrus as a familiar storage service with additional guarantees. Together, these trends point toward Walrus occupying a niche that is small in raw bytes but large in economic value.

The competitive threats are also specific. Walrus is most vulnerable if a competitor can offer comparable programmability and access control with materially lower overhead for small objects, because that would expand the workloads where decentralized storage becomes default. It is also vulnerable if permanence becomes the dominant storage narrative, because Walrus is built around renewable custody rather than one-time payments for eternal storage. But Walrus is defensible if the market moves toward regulated, policy-heavy data flows where access control, auditability, and lifecycle management are mandatory. In that world, Walrus’s choice to keep base blobs public by default while providing a first-class encryption and access-control overlay is not a weakness. It is a clean separation of concerns.

The way to understand Walrus’s trajectory is straightforward. Walrus is trying to turn storage from a passive commodity into a programmable financial primitive with explicit time, explicit proofs, and explicit policy hooks. The WAL token is the budget unit that funds custody across time, and the staking and penalty design is an attempt to price in the real costs of churn and migration rather than pretending they do not exist. If Walrus succeeds, it will not be because it beats cloud storage on raw durability promises or because it out-markets older decentralized storage networks. It will be because developers and institutions begin to treat data as an onchain object with enforceable custody and access rules, and Walrus becomes the default place those objects live inside the Sui ecosystem. If it fails, it will likely be because the market never demanded that primitive at scale, or because the overheads that buy auditability and programmability were not justified by enough high-value workloads. Either way, Walrus is one of the clearer infrastructure bets today, not on storing bytes, but on making custody and access to those bytes legible, tradeable, and enforceable in the same onchain language that capital already uses.