“Available” is not a property. It’s an agreement that can expire.

“Available” is not a property. It’s an agreement that can expire.

In Web3 storage, data availability is often treated like a guarantee: the network stores data, so the data is available. It sounds binary, almost mathematical.

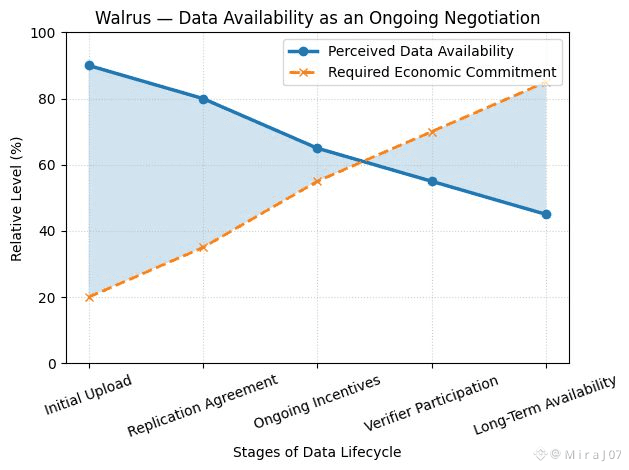

But in real decentralized systems, availability isn’t a fixed truth. It’s the outcome of incentives, coordination, and time.

Which means something uncomfortable:

Data availability is a negotiation, not a guarantee.

That is the right lens for evaluating Walrus (WAL).

Why “availability” feels like a guarantee (until it doesn’t)

Most users experience availability on good days:

data loads instantly,

retrieval works on the first attempt,

costs are predictable,

the network looks healthy.

So “available” becomes a belief: if the system stored it, the system will serve it.

But decentralized storage isn’t a vending machine. It’s a market.

And markets don’t guarantee outcomes. They negotiate them.

Availability is negotiated between incentives and effort

For data to be available, someone must do work:

store it reliably,

keep replicas healthy,

repair degradation,

serve retrieval requests,

maintain uptime during churn.

That work is not free. It’s economically motivated.

So availability is always the result of a negotiation:

How much are users paying (directly or indirectly)?

How much does it cost operators to serve?

Are incentives strong enough to force repair?

Is demand high enough to keep attention alive?

When those terms drift, availability drifts.

The negotiation becomes visible when the system is stressed

You only notice availability is negotiable when:

token price drops and operator participation weakens,

demand spikes and retrieval becomes congested,

the app disappears and no one monitors long-tail data,

repair is delayed because “it’s still fine,”

gateways become bottlenecks.

At that point, “available” turns into a conversation:

“Try again later.”

“Use a different endpoint.”

“It’s still there somewhere.”

“We’re investigating.”

That’s negotiation language not guarantee language.

The real danger: availability can be technically true and practically false

A network can claim availability because:

replicas exist,

data hasn’t been deleted,

hashes verify.

But user reality cares about:

time-to-retrieve,

cost-to-recover,

completeness,

consistency across requests.

If retrieval becomes slow, expensive, or unreliable, availability becomes a technicality not a service.

This is how users lose disputes, audits fail, and recoveries collapse even when the data “exists.”

Walrus treats availability as a long-horizon obligation, not a marketing claim

Walrus doesn’t assume availability will persist automatically. It assumes the negotiation will change over time and designs to keep the outcome stable even when conditions drift.

That means focusing on:

early visibility of degradation (so the negotiation doesn’t fail silently),

enforceable consequences for neglect (so silence isn’t the dominant strategy),

repair incentives that remain rational even when demand is low,

accountability that doesn’t vanish into “the network.”

In other words: Walrus tries to engineer availability into behavior, not into hope.

Why this matters now: availability is becoming financial infrastructure

Storage now underwrites:

settlement proofs,

governance legitimacy,

compliance and audit trails,

recovery snapshots,

AI dataset provenance.

In these contexts, availability cannot be “negotiated” in real time by whoever happens to be online. It must be dependable, predictable, and defensible.

Because when availability is negotiable, it becomes power:

the party who can retrieve proof fastest wins,

the party who can pay more gets served first,

the party with better infrastructure routes around failure.

Walrus aligns with this maturity by treating availability as a governed commitment.

I stopped asking “Is the data available?”

Because the real question is:

Under what conditions does the system stop making it available?

That’s the only question that matters in risk management.

So I started asking:

When do incentives weaken enough to delay repair?

When does recoverability expire before availability does?

Who is forced to act before users suffer?

What happens when demand is low and attention disappears?

Those questions expose whether availability is a guarantee — or a temporary truce.

Walrus earns relevance by designing for the hard version of availability: the one that survives time, neglect, and stress.

Availability is a negotiation the best systems just don’t make you feel it.

The strongest storage networks are not the ones that claim “always available.” They’re the ones that keep the negotiation stable enough that users never have to bargain for their own data.

Walrus matters because it treats availability as something that must be enforced, not assumed.

A guarantee is what you say in a whitepaper; availability is what the network agrees to deliver when nobody is watching.