There’s a particular kind of panic that doesn’t feel dramatic until it happens to you. You go back to a link you saved because you needed it to exist—an archive, a dataset, a proof, a recording—and it’s gone. Not with fireworks. Just… missing. The page refreshes into a blank space where certainty used to live. And in that moment you realize how much of the internet is held together by polite agreements: the hosting bill gets paid, the account stays in good standing, the platform keeps approving the content, the company survives the quarter. When any one of those agreements breaks, “truth” can evaporate.

Walrus is built for that feeling. Not the hype version of “decentralized storage,” but the gritty version where censorship resistance is measured by what remains available after incentives shift, after participants churn, after networks lag, after pressure shows up in the quiet places. Mysten’s own framing doesn’t hide the ambition: Walrus is powered by Sui for coordination, designed to scale horizontally, and intended to compete on cost at exabyte scale. That is a big claim, but it also points to the real battleground. If a storage network can’t scale without drifting into a few dominant operators, then “censorship resistant” becomes a decorative label.

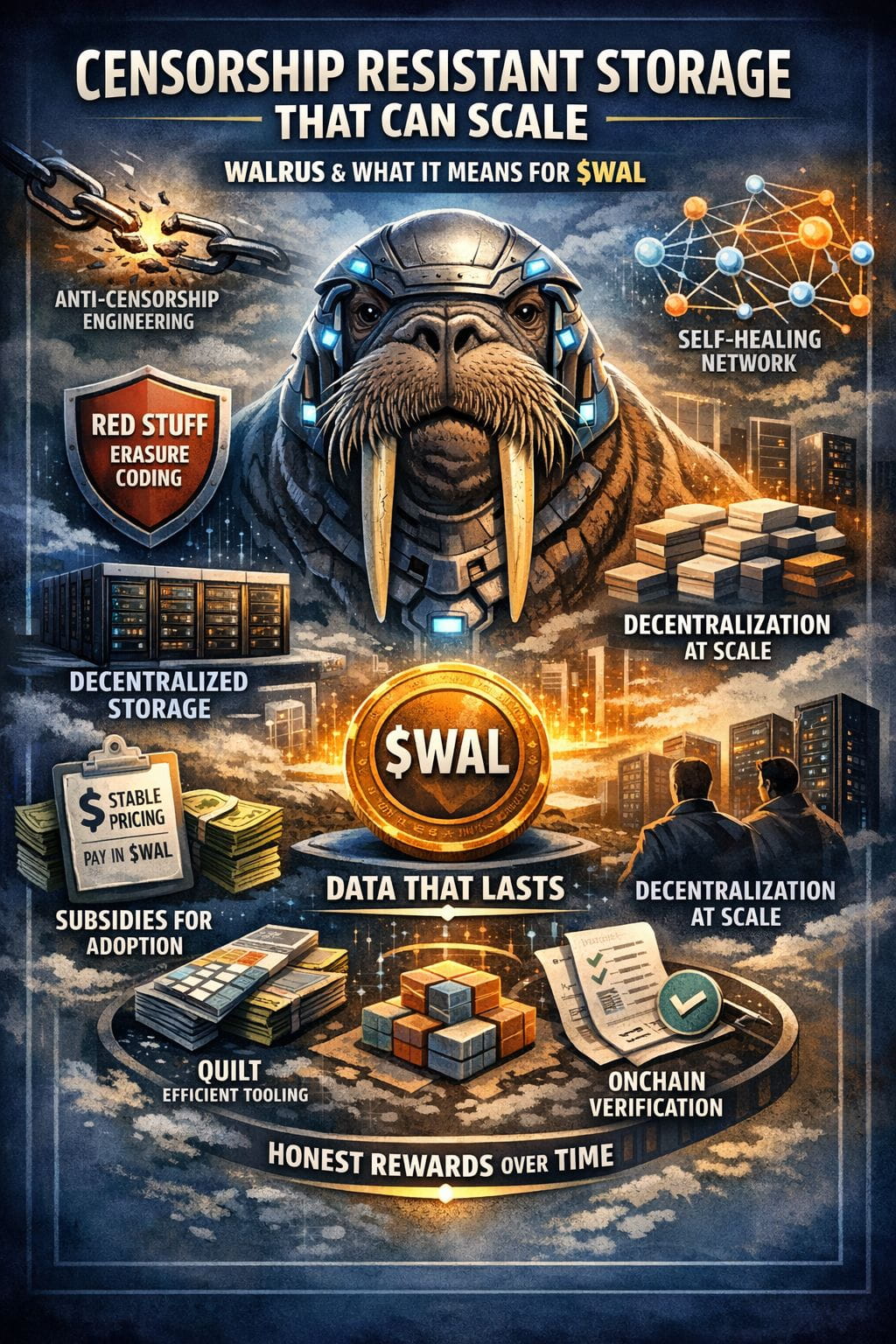

The heart of Walrus is a design choice that feels almost philosophical: assume the world is hostile and messy. Storage networks often fail in two boring ways. First, repair becomes too expensive, so only large operators can survive, and decentralization collapses quietly. Second, verification assumes clean timing, so attackers exploit delays to look honest without actually doing the hard work of storing data. Walrus tries to dodge both traps with Red Stuff, its two-dimensional erasure coding system. The paper presents Red Stuff as a way to achieve high security with a relatively low overhead (including an indicated 4.5x replication factor for the security target discussed), while keeping the network “self-healing” so repair bandwidth scales with what was truly lost instead of turning into a constant network-wide penalty.

That self-healing detail matters more than people think. Because the enemy of censorship resistance is not only censorship—it’s exhaustion. If a network is expensive to maintain, you don’t need to censor it aggressively. You just wait while the economics squeeze out smaller participants. Over time the system centralizes, and then censorship becomes easy again. A repair model that stays proportional under churn is, in a very real sense, anti-censorship engineering.

Walrus goes one step further and builds verification as if the internet is going to misbehave—because it will. The Walrus paper calls out asynchronous storage challenges, designed to prevent adversaries from exploiting network delays to pass checks without genuinely storing data over time. This is the difference between “we verified it once” and “we forced reality to keep proving itself.” If you care about censorship resistance, that distinction is everything. A system that only works under tidy assumptions eventually becomes a system you trust socially. And social trust is where pressure loves to hide.

Then there’s the time problem: storage is not an event, it’s a commitment. Walrus emphasizes epoch-based operation and describes a multi-stage epoch change protocol intended to maintain uninterrupted availability during committee transitions. That’s not a flashy feature, but it’s the sort of thing you only build if you’re serious about real usage. When storage is meant to last, the most dangerous moments are the in-between moments—the reconfigurations, the handoffs, the churn. Those are the moments where “decentralized” systems most often wobble.

Sui’s role in Walrus is also more than branding. In Walrus, blobs are represented as onchain objects on Sui, and the lifecycle of storing a blob includes onchain steps like registering/reserving and then certifying availability. The developer docs spell it out: storing can involve multiple Sui transactions, with gas paid in SUI. This creates a shared, hard-to-quietly-edit record of what was promised and certified. It doesn’t magically solve censorship on its own, but it reduces the space where the story can be rewritten without leaving fingerprints.

And Walrus is unusually direct about cost, which I take as a good sign. The developer docs explain that encoded storage is roughly about five times the original blob size plus metadata, and Walrus’s own staking rewards post echoes the same reality: pricing reflects that the system stores roughly five times the raw data, described as near the frontier of replication efficiency for decentralized storage. This is not a marketing-friendly number. It’s a real number. And real numbers matter because they force you to confront what decentralization actually costs.

That cost honesty also explains why Walrus invests in practical tooling like Quilt. The docs note that for small blobs, fixed overhead and metadata can dominate, and Quilt groups many small files together to amortize those costs. The year-in-review later frames Quilt as a meaningful cost saver for partners at scale. Whether you take the exact magnitude at face value or not, the direction is clear: Walrus is thinking about real workloads, not just protocol purity.

Now zoom in on $WAL, because this is where architecture becomes economics, and economics becomes behavior. WAL is the payment token for storage, and Walrus explicitly targets a stable fiat-denominated pricing experience so users aren’t forced to live inside token volatility just to store data. That’s a surprisingly human decision. It’s basically admitting: “People budget in dollars. They want predictability. If we want to be infrastructure, we have to feel like infrastructure.”

But the deeper point is time alignment. Walrus describes a model where users pay upfront, and rewards flow over time to support sustained availability rather than rewarding only the moment a blob is written. I keep coming back to this because it’s one of the few token designs that actually matches the lived reality of storage. If you pay once and operators get paid once, you’re trusting that they’ll remain honest later. Walrus is trying to make honesty a recurring paycheck instead of a one-time tip.

Subsidies are the early-stage accelerator that makes that model workable. Walrus describes an allocation for subsidies meant to support adoption and allow storage below market while still keeping operators viable. This can look like “growth,” but it’s also something more structural: you’re paying the market to form. You’re buying the chance for real usage to happen early enough that the protocol gets tested under genuine load, not just theory.

Then comes the uncomfortable part: decentralization is fragile when things start working. If Walrus becomes truly useful, stake concentration pressure will show up. Operator consolidation pressure will show up. Convenience will tempt the system toward a smaller set of dominant providers. Walrus’s decentralization-at-scale writing acknowledges this and emphasizes delegation, performance-based rewards, and penalties for misbehavior as a way to preserve a broad operator set. The practical meaning is simple: censorship resistance is not a belief system. It’s a set of incentives that must remain sharper than the temptations of centralization.

Adoption signals don’t prove everything, but they do create a kind of accountability. Walrus’s 2025 year-in-review points to mainnet launch timing and a spread of ecosystem use cases, and later writing highlights large-scale migrations like Team Liquid moving 250TB. Even if you treat these as curated examples, they still imply something important: Walrus is deliberately aiming at messy, heavyweight data, the kind that breaks fragile systems. That’s where the protocol’s promises either hold—or they don’t.

Walrus also wants to be more than “storage.” Mysten has framed it as both decentralized storage and a data availability layer that other systems (including rollups) can use by posting blobs for reconstruction. The Walrus paper situates these choices among broader DA and coding approaches and the practical constraints real systems run into. This matters for $WAL because it widens the kinds of demand that can become sticky: not just archiving files, but serving as a backbone for applications that need verifiable availability without inheriting the cost of replicating everything on a base chain forever.

If I had to humanize Walrus into a single idea, it would be this: Walrus is trying to make “data staying alive” feel less like a favor and more like a law of physics. Red Stuff is there to keep repair from crushing smaller participants. Asynchronous challenges are there because the real internet is chaotic. Epoch transitions are there because time is the real enemy of reliability. Onchain objects and certification are there so the history of promises has a backbone. Tooling like Quilt exists because practical cost leaks are how people lose faith.

And in that story, $WAL isn’t just a token you hold. It’s the unit you pay when you want your data to outlive moods, platforms, and gatekeepers—and the unit operators earn only if they keep doing the boring, honest work of making availability true over time. If Walrus succeeds, the most valuable thing it creates won’t be a new place to store files. It will be a new default expectation: that once data is committed and paid for, it’s harder to erase than to preserve, and the cost of silencing it becomes too high to be the easy option.