A while ago I was cleaning up some old trading research. Just basic stuff I like to keep around price history, simulation results, and a few machine learning experiments I sometimes revisit. I had everything sitting on regular cloud storage, which works fine until you start thinking about dependency. One provider change, one pricing update, or one account issue and suddenly your entire archive is someone else’s problem.

So I tried moving part of it into decentralized storage. On paper, that felt like the right move. In reality, it was frustrating. One network charged far more than I expected just to upload a few gigabytes. Another claimed high availability, but during a short network hiccup my files were unreachable for hours. Nothing catastrophic happened, but the experience made something very clear to me. Decentralized storage still struggles with real world consistency.

The core issue is that many systems are built more around ideals than everyday usage. To guarantee durability, they rely on extreme redundancy. Files get copied again and again across the network. That protects against failure, but it also makes costs climb fast. And even with all that replication, performance can still degrade when traffic increases. If you are working with AI datasets or large media files, the problems show up quickly. Reads slow down, pricing feels unstable, and access rules feel layered on rather than built in.

It reminded me of a public archive spread across dozens of buildings. In theory, nothing ever disappears. In practice, retrieving one document can become an unnecessary process. Redundancy only helps if access stays smooth under pressure.

Walrus takes a noticeably different approach. Instead of trying to be everything for every file size, it focuses directly on large blobs things like datasets, video content, model checkpoints, and archives. Rather than replicating full copies everywhere, it uses erasure coding to keep redundancy closer to four or five times. That still protects availability, but without turning storage into a cost sink.

Coordination and verification happen through $SUI , which allows applications to confirm that data exists and is properly distributed without needing to fetch the entire file. What stood out to me is how programmable the storage layer is. With features like Seal introduced in late 2025, developers can define access conditions directly at the storage level. That matters when dealing with permissioned AI models or gated datasets. Smaller files are bundled using Quilt so the system does not get cluttered with tiny objects.

This is not just conceptual design either. Pudgy Penguins expanded their storage footprint from one terabyte to six, and OpenGradient is already using Walrus for controlled model storage. That tells me actual builders are testing the system beyond demos.

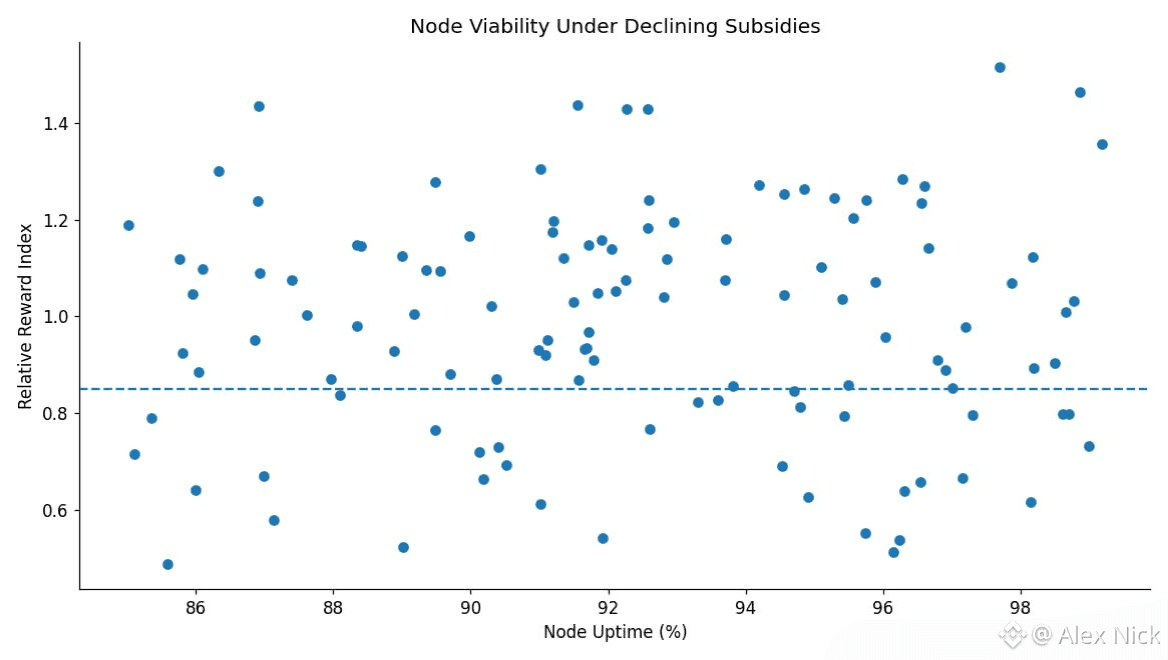

Now when it comes to the WAL token itself, the mechanics are fairly clean. WAL is used to pay for storage, with pricing designed to stay relatively stable in dollar terms instead of swinging wildly with market volatility. Fees are distributed gradually rather than instantly, which reduces sharp payout pressure. Staking is mostly delegated and determines which nodes participate in storage committees. Rewards depend on performance and uptime, not just token quantity.

Governance operates through stake weighted voting, covering things like upgrades, penalties, and protocol parameters. Slashing was introduced after mainnet to enforce reliability. There are no flashy burn narratives here. Value capture comes mainly from actual usage and penalties when nodes underperform. From a system design standpoint, it is predictable, which is often underestimated in crypto.

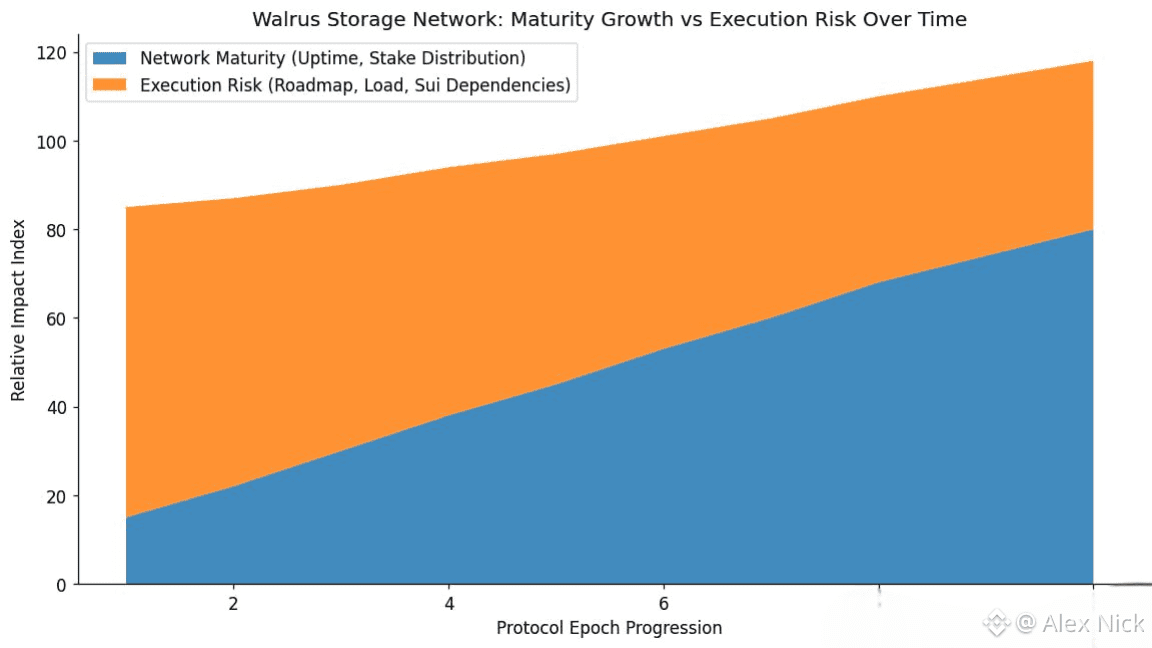

Where things get more complex is supply.

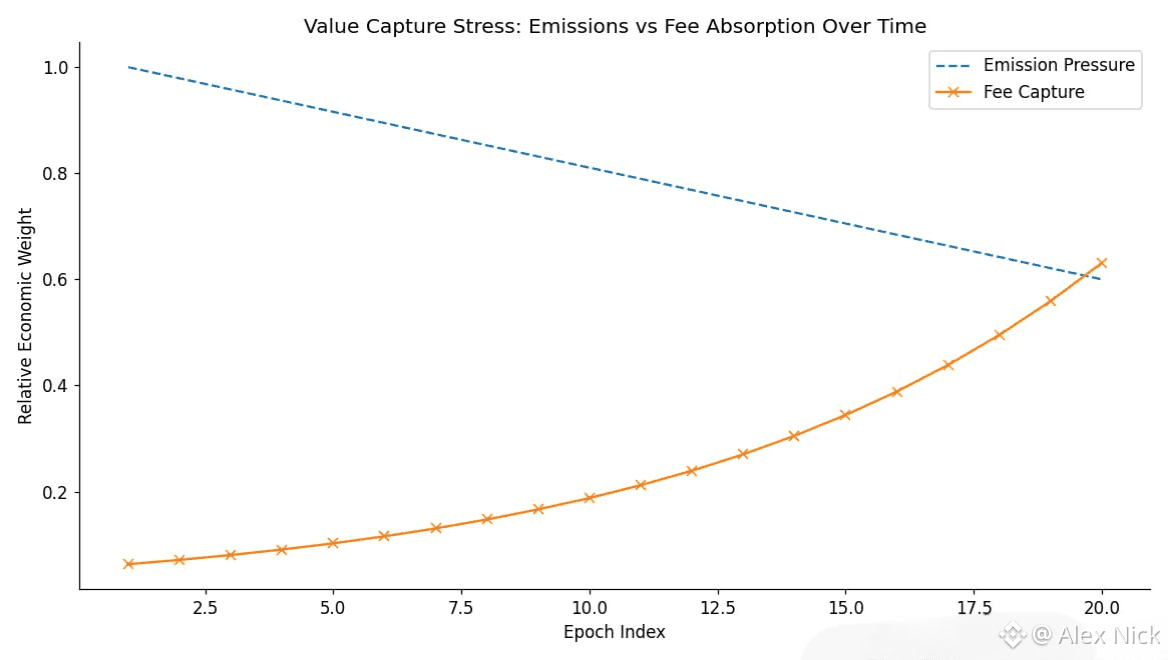

Walrus has a maximum supply of five billion WAL. Circulating supply is still well below that number, but it continues to increase as unlocks roll out. Ecosystem incentives, community distributions, and early allocations all contribute to ongoing emissions. That means a significant portion of supply expansion is still ahead, not already priced in.

Short term price behavior tends to react strongly around unlock events. Airdrops and subsidy releases showed how quickly sell pressure can appear when recipients choose liquidity over long term exposure. Market cap and volume can look healthy during those moments, but they do not tell the full story.

The real question is not whether unlocks happen. They always do. The question is whether demand grows fast enough to absorb them naturally.

Storage networks rarely fail in dramatic ways. They do not collapse overnight. What usually happens instead is slow erosion. Retrieval speeds worsen. Reliability slips. Operators lose incentives. Builders quietly move elsewhere. Price reacts only after confidence is already gone.

That is the true risk layer behind circulating versus max supply. If storage demand becomes habitual, meaning projects keep paying for storage long after incentives fade, fees and penalties can begin to counter emissions. If usage stays shallow, token supply expansion becomes a constant weight on the system.

Walrus still has a clear runway. The architecture is strong, integrations are real, and programmable data is a genuine differentiator in an AI driven market. But tokenomics do not respond to intentions. They respond to behavior.

Whether WAL captures lasting value will not be decided during hype cycles. It will show up quietly in repeat usage. When teams return for second uploads. When datasets stay hosted months later. When storage becomes something builders rely on rather than test.

That slow repetition is what ultimately determines whether growing circulation becomes manageable or turns into persistent pressure. And like most real infrastructure stories, the answer will not arrive loudly. It will arrive through consistency.