@Walrus 🦭/acc There’s a quiet shift happening in Web3 storage, driven by a practical pain: apps now need speed. “Hot storage” is data you fetch constantly—images, game assets, datasets, logs, media libraries. On-chain is great in theory, brutal in cost. So teams shift off-chain, and suddenly the hard part isn’t computation—it’s credibility: who can be trusted, and how do you prove it?

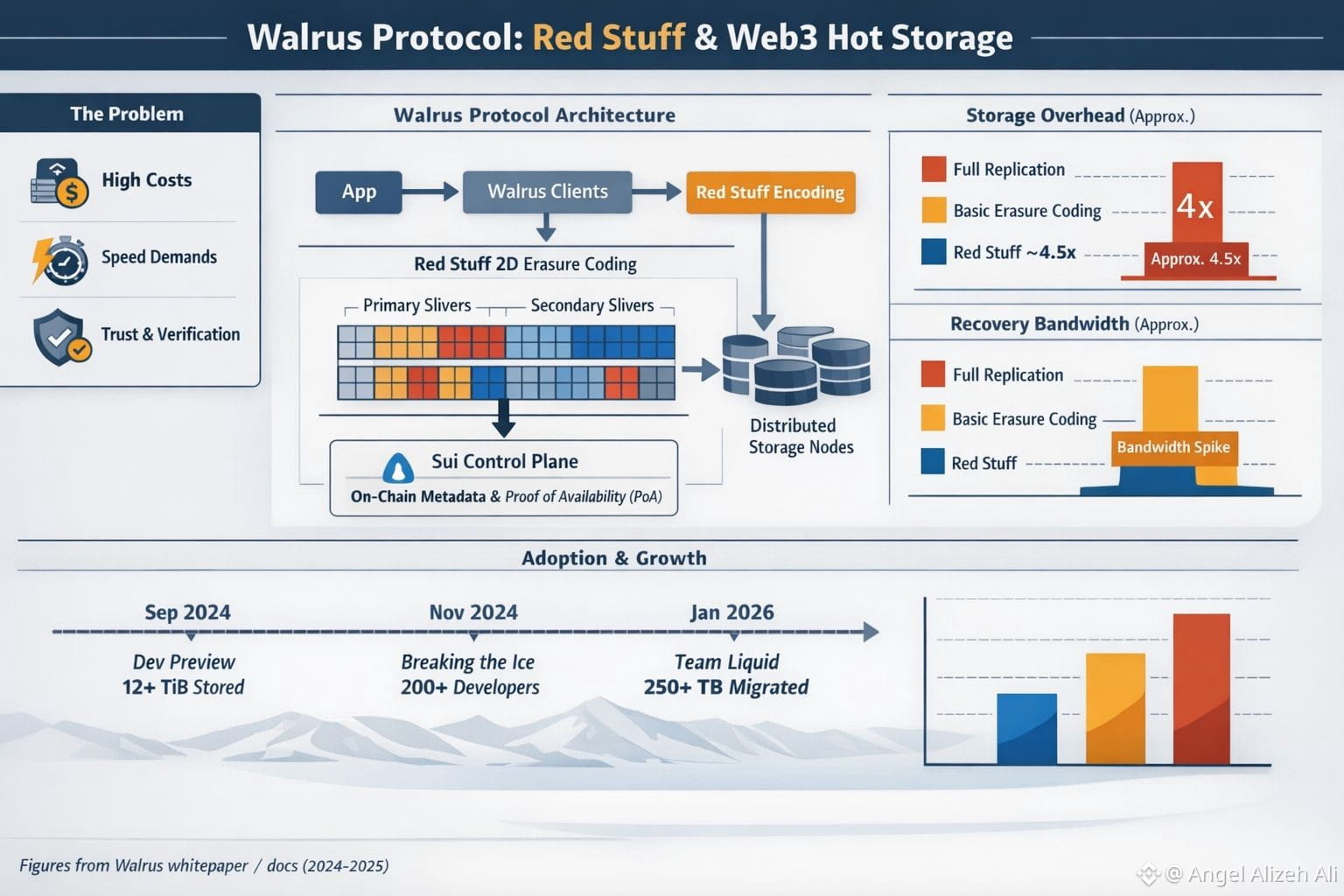

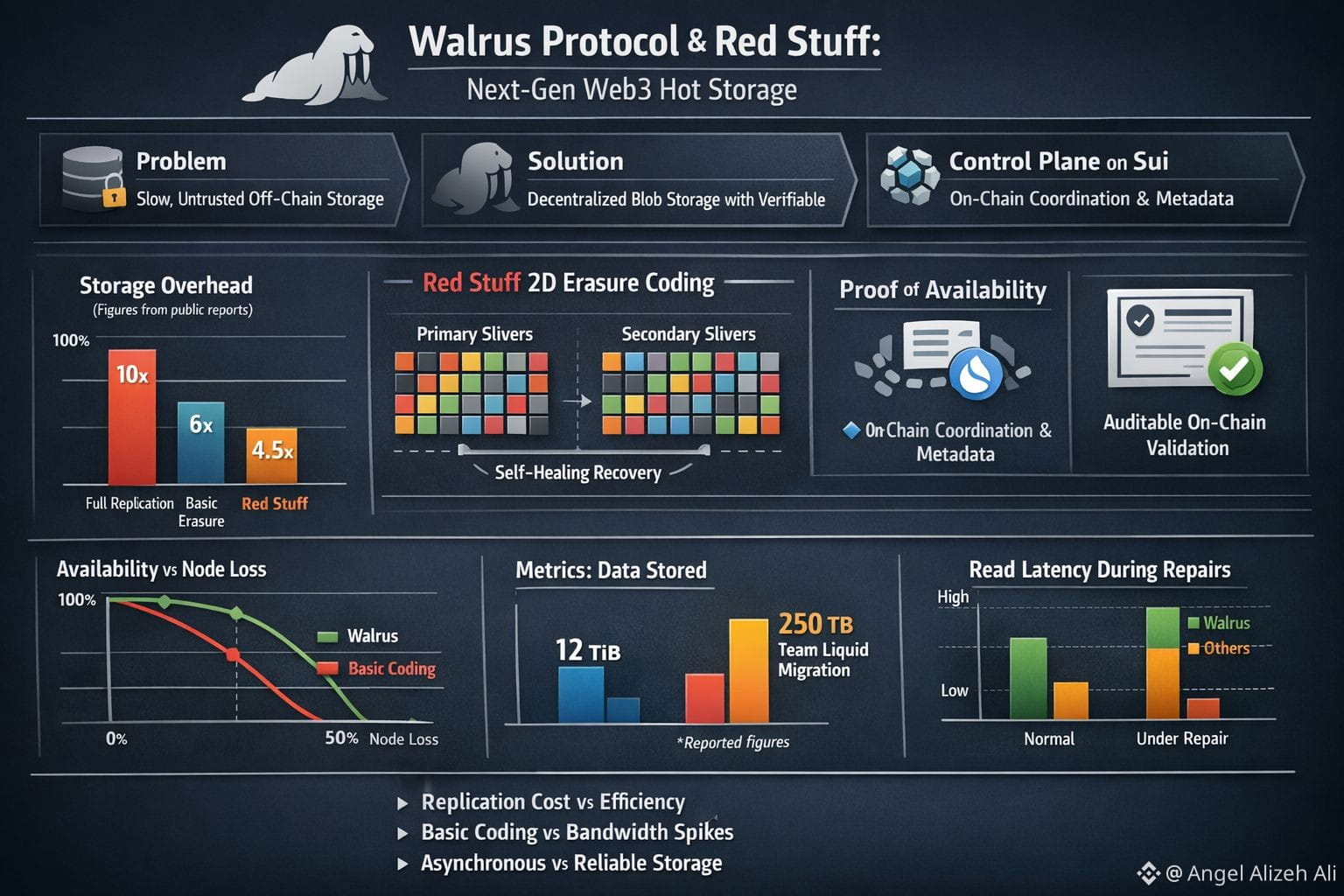

Walrus Protocol feels relevant because it targets that gap between speed and verifiability. Mysten Labs introduced Walrus as a decentralized blob storage and data-availability protocol for large, unstructured files that don’t belong inside a validator’s state. The core move is to encode a file into smaller fragments (often called slivers), distribute them across storage nodes, and make reconstruction possible even if some pieces go missing.

What gives Walrus sharper definition is its encoding engine, Red Stuff. Red Stuff is described as a two-dimensional erasure coding scheme that produces primary and secondary slivers arranged in a matrix, with self-healing recovery when nodes fail. For hot storage, that recovery behavior is the point. A slow read is indistinguishable from downtime, and many decentralized systems buckle when churn forces repairs. Walrus is trying to make repairs look like routine maintenance instead of a network-wide emergency.

The Walrus paper is candid about the trade-offs it wants to escape. Full replication is simple but wasteful, while basic erasure coding can create bandwidth spikes during outages or attacks. The paper claims Red Stuff reaches high security with about a 4.5x replication factor, and it emphasizes storage challenges in asynchronous networks—so a node shouldn’t be able to “look available” by exploiting network delays while not actually storing data. If your application depends on media or datasets being there tomorrow, that kind of adversarial thinking stops being theoretical.

Walrus becomes more relevant when you look at how it plugs into applications. A defining characteristic is that Walrus outsources control-plane functions to Sui, using the chain for coordination, metadata, and verifiable proofs. The Walrus Foundation describes a Proof of Availability recorded on Sui as an on-chain certificate that a blob has been correctly encoded and distributed, creating a public audit trail and marking the official start of the storage service. The docs frame the same idea in simple terms: you can write and read blobs, and anyone can prove a blob was stored and will remain available for later retrieval. Walrus’s own materials also frame this as “programmable storage”: blobs and storage capacity can be represented as objects on Sui, and the protocol positions itself as chain-agnostic through developer tools and SDKs.

There’s also a practical signal behind the concept. By September 2024, Mysten Labs said the Walrus developer preview was already storing over 12 TiB of data, and an event called Breaking the Ice drew more than 200 developers building with decentralized storage. That doesn’t prove durability, but it does suggest Walrus is being shaped by real integration pain, not just theory.

This is why Walrus is getting attention now rather than drifting in “someday” territory. Web3 stacks are becoming more modular, and the center of gravity is shifting toward blobs—video, images, PDFs, datasets, and the cryptographic artifacts modern systems generate. Walrus leans into that reality by framing storage as something that can be coordinated and verified on-chain while keeping the heavy data plane specialized for throughput. The AI part makes this feel way more urgent—not because of hype, but because teams actually need provenance and reproducibility. They want to trace exactly which dataset version trained which model, who touched it, and whether any files quietly changed between runs. A custody proof plus reliable retrieval won’t magically fix governance or licensing, but it does make real accountability possible without dragging everything back into one central chokepoint.

There are early signs Walrus is being tested against real workloads. In late January 2026, Team Liquid announced migrating more than 250TB of historical match footage and brand content to Walrus, described as the largest single dataset entrusted to the protocol to date. Media archives are a brutal proving ground because the files aren’t just stored—they’re constantly accessed, clipped, and repurposed by distributed teams.

None of this magically solves decentralized hot storage. Incentives have to stay aligned so nodes keep serving data, and developer tooling has to feel predictable. But Walrus is relevant precisely because it treats hot storage as it actually exists: big files, frequent reads, node churn, and a need for verifiable guarantees that don’t rely on a single provider’s good behavior.