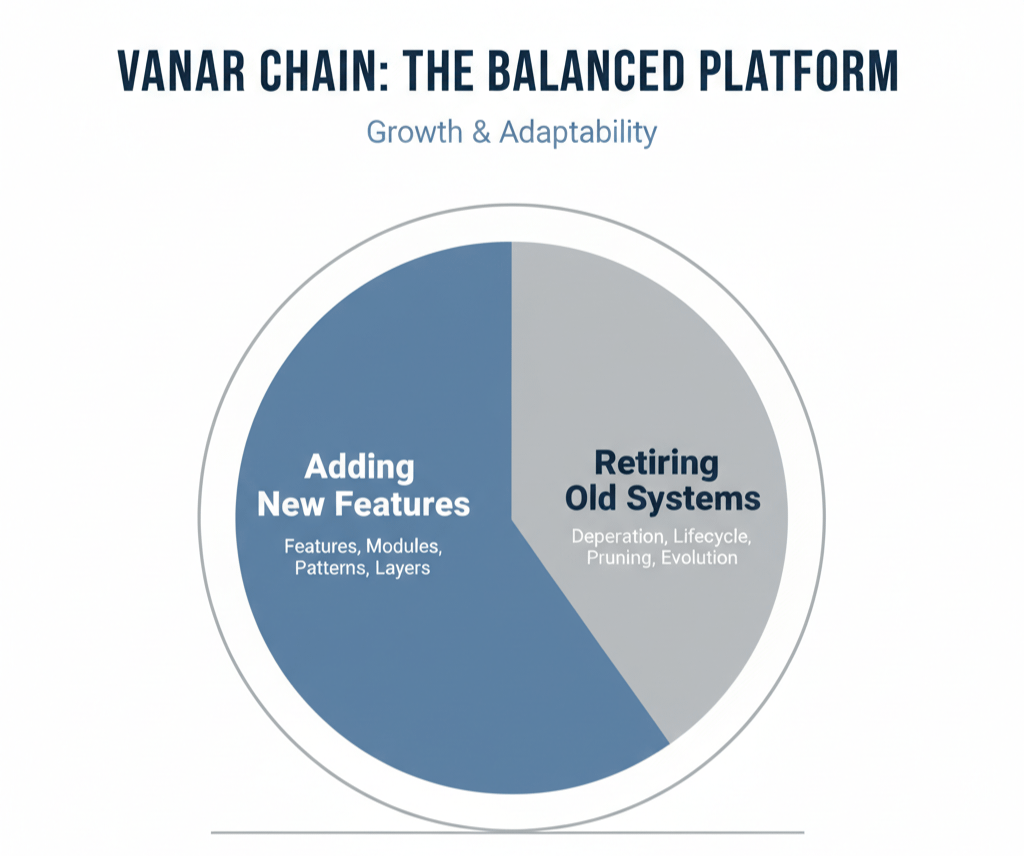

Most platforms are very good at adding things.

New features.

New modules.

New patterns.

New layers.

They’re much worse at removing things.

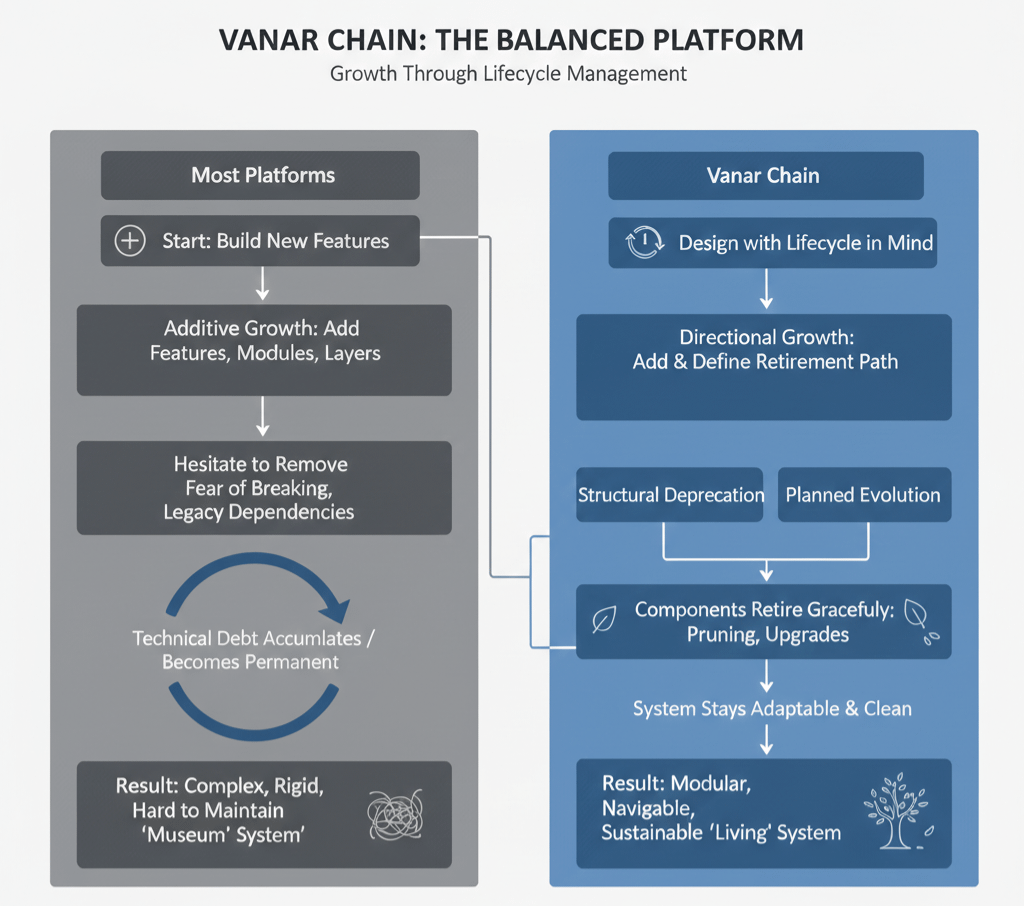

In a lot of ecosystems, nothing ever really dies. Old paths stay half-supported. Legacy assumptions linger. Deprecated features keep working “for now,” which quietly turns into “forever.” Over time, the system becomes a museum of decisions that once made sense but no longer quite fit together.

Vanar Chain doesn’t feel like it’s designed for that kind of accumulation.

It feels like a system that understands something most infrastructure avoids admitting: long-lived platforms need a healthy way to retire ideas, not just invent new ones.

That’s a very different mindset.

In many stacks, deprecation is treated as a social problem. You announce it. You warn people. You wait. You extend the deadline. You wait again. Eventually, you either break something or give up. The technical system just sits there, passive, while humans negotiate around it.

Vanar’s design direction suggests it wants deprecation to be more structural than political.

Not “please stop using this.”

But “this has a lifecycle and that lifecycle is part of how the system works.”

That changes how you build things in the first place.

When engineers know that components have a clear path to being retired, they design with endings in mind, not just beginnings. Interfaces become easier to replace. Assumptions become easier to challenge. The system stays adaptable instead of slowly hardening around yesterday’s choices.

In ecosystems without that mindset, every decision becomes permanent by accident.

People hesitate to improve things because improvements imply migrations. Migrations imply risk. Risk implies meetings. And meetings imply delay. So the old path stays, even when everyone knows it’s no longer the right one.

That’s how technical debt turns into technical gravity.

Vanar feels like it’s trying to resist that gravity by making change over time directional, not just additive.

There’s also an operational benefit here.

Systems that never let go get harder to operate. Not because they’re bigger, but because they’re denser. Every incident touches more code paths. Every fix has to consider more legacy behavior. Every upgrade carries more invisible constraints.

When a platform has a clear concept of lifecycle, the surface area stays intentional. The system can still grow but it doesn’t grow in every direction at once.

That’s the difference between a city that expands with zoning and a city that expands by accident.

Both get bigger.

Only one stays navigable.

Vanar’s approach seems closer to the first.

Not by being rigid.

But by acknowledging that healthy systems prune as much as they grow.

There’s a human side to this too.

In many organizations, legacy systems become untouchable not because they’re sacred, but because nobody wants to be responsible for breaking something that’s been around forever. That fear leads to stagnation. The platform becomes something you work around instead of something you evolve.

When deprecation is normalized and structured, that fear changes shape. Retiring something becomes a planned operation, not a heroic risk. People stop treating old components like landmines and start treating them like chapters that can actually end.

That’s psychologically important.

It turns maintenance from avoidance into stewardship.

Another subtle effect shows up in ecosystem clarity.

In platforms where nothing ever really goes away, newcomers have to learn everything: the current way, the old way, the older way, and the “don’t use this but it’s still here” way. The learning curve becomes less about understanding the present and more about navigating history.

Systems that know how to sunset things keep the present cleaner.

Not simpler.

Just less haunted by choices that no longer matter.

Vanar feels like it’s aiming for that kind of cleanliness, not by erasing the past, but by giving it a respectful exit.

There’s also a strategic angle here.

Platforms that can’t retire things get stuck. Every improvement has to be backward-compatible with every old decision. Over time, innovation slows, not because ideas run out but because the cost of carrying the past becomes too high.

Platforms that treat deprecation as normal can evolve without breaking their own spine. They still respect users. They still provide transitions. But they don’t confuse continuity with immobility.

Vanar’s design posture suggests it wants continuity with direction, not continuity at all costs.

From the outside, this is hard to see.

Nobody advertises “we’re good at removing things.”

Nobody ships a press release for “this path was retired cleanly.”

Nobody celebrates the feature that doesn’t exist anymore.

But in mature systems, that’s often the real signal of health.

Because growth isn’t just about adding capabilities.

It’s about making room for better ones.

What stands out about Vanar is that it doesn’t seem to treat its architecture like a shrine to past decisions. It feels more like a living structure, one that expects parts of itself to change, age and eventually step aside.

That’s not instability.

That’s maintenance at the level of design.

In the long run, platforms that survive aren’t the ones that keep everything forever.

They’re the ones that know what to keep, what to evolve and what to let go without turning every change into a crisis.

Vanar feels like it’s building for that future.

Not one where nothing is lost.

But one where what’s lost makes the system stronger, not more fragile.

And that’s a rare kind of maturity in infrastructure.