Last year I sat in a messy video call with a product lead and a legal person from a consumer brand. The app was simple on paper. Users upload documents and receipts, the app turns them into “facts” the system can use, and the brand wants proof later that nothing was changed after the fact. The legal person kept repeating one line: “If it is auditable, it must be public.” I had the same belief for a long time, until I saw how Client-Side Encryption and the Document Storage Smart Contract change the problem. The moment I noticed the hard limit of 65KB for AI embeddings per document, and the way the chain only shows high entropy writes tied to owner addresses, “audit without exposure” stopped sounding like a debate and started sounding like a design.

The mispriced assumption is that auditability requires everyone to see your data. That is not what most real teams mean when they say “audit.” In practice they want three things. They want to prove who owned a piece of information at a point in time. They want a history of edits that cannot be rewritten in secret. And they want to show that history to an auditor without leaking the content to the whole world. Public data can help with those goals, but it also creates a new risk. Once something is public, you cannot take it back. A single leak can turn a brand campaign into a compliance event.

In that brand call, this was the part that decided whether the lawyers would let the feature ship. The network chooses what it reveals by default and what it keeps hidden by default. Many chains treat that choice as an app problem. In a real adoption setting, that is too late. If the base behavior pushes teams to publish sensitive text, they will either not ship, or they will ship and regret it.

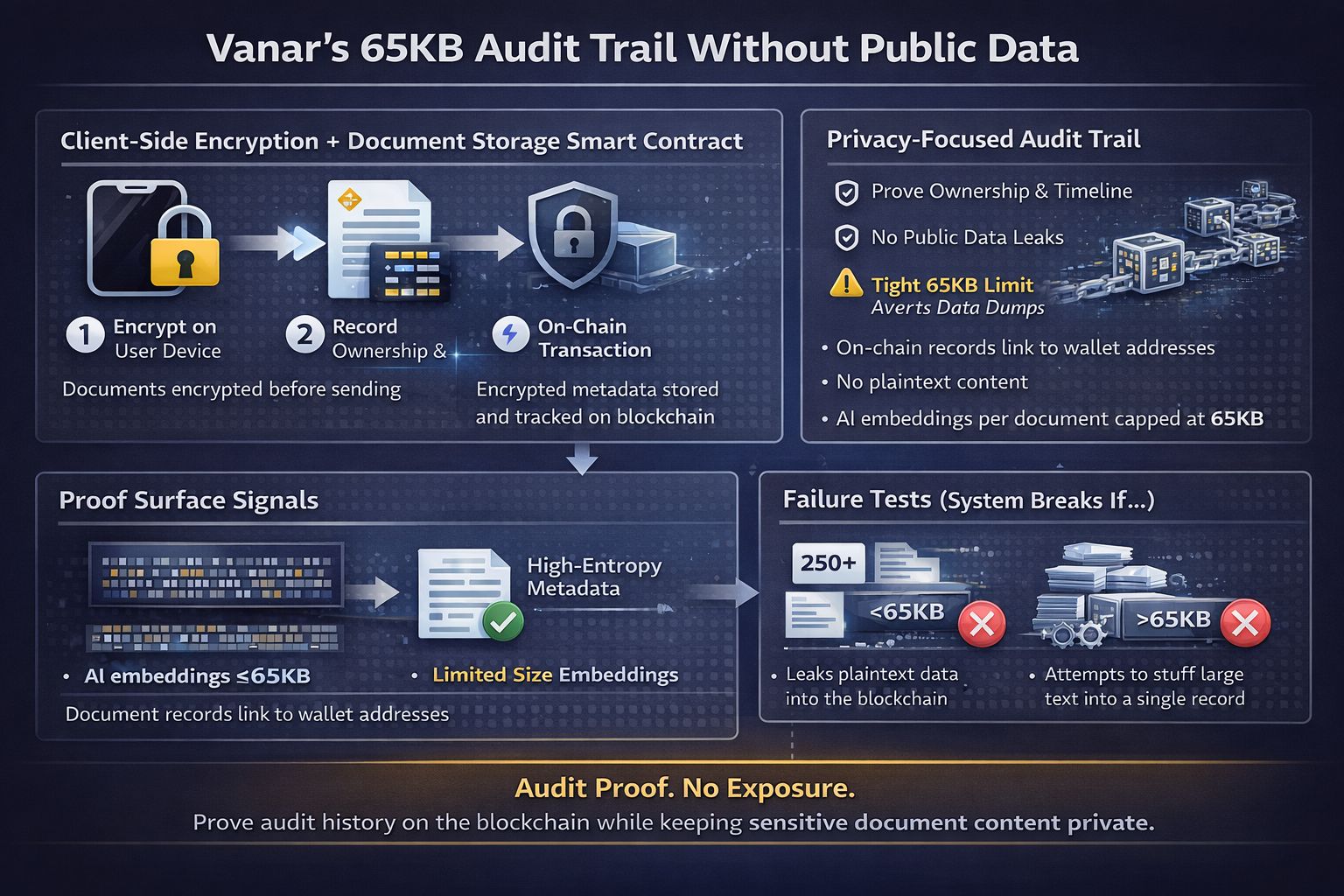

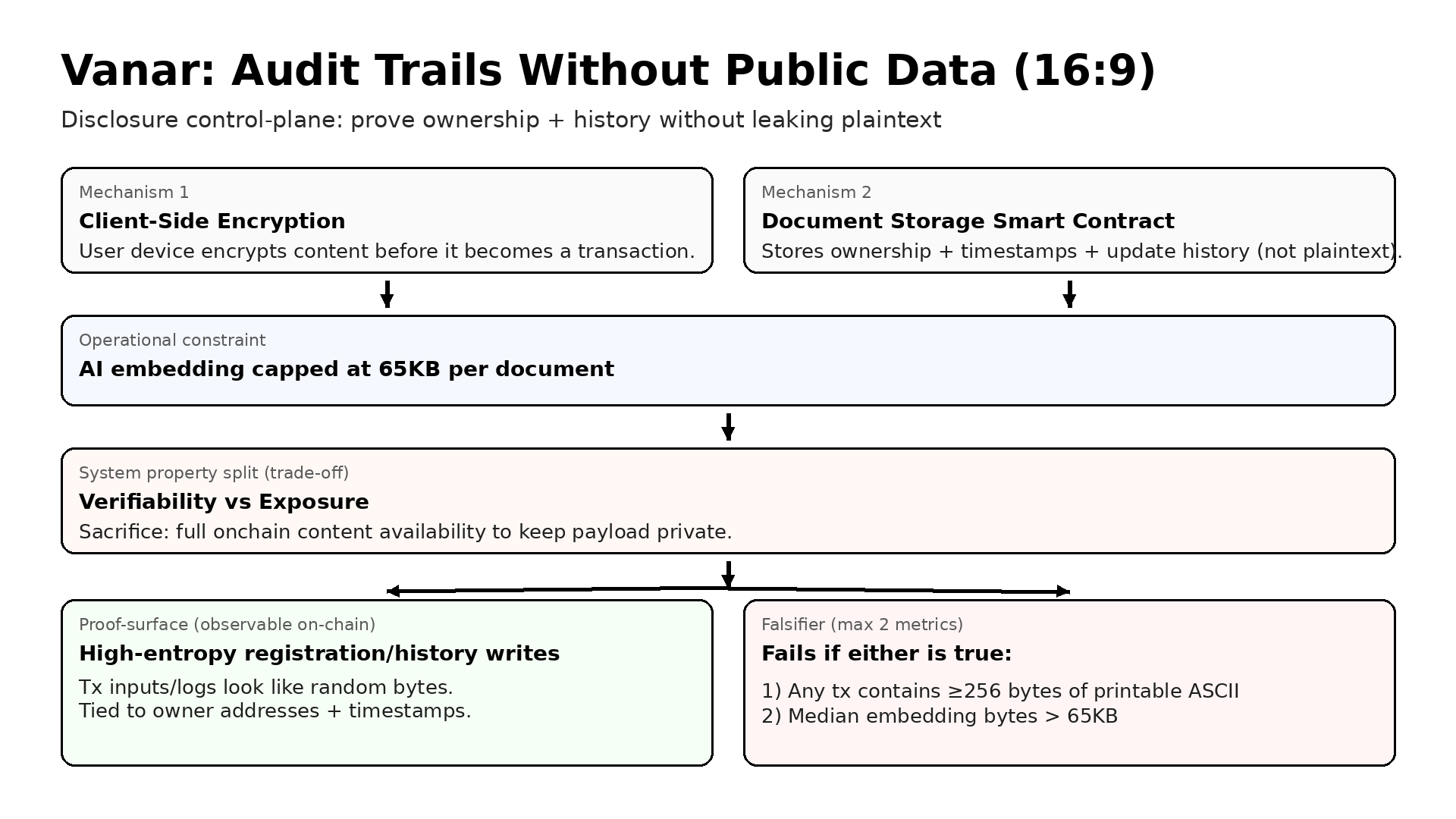

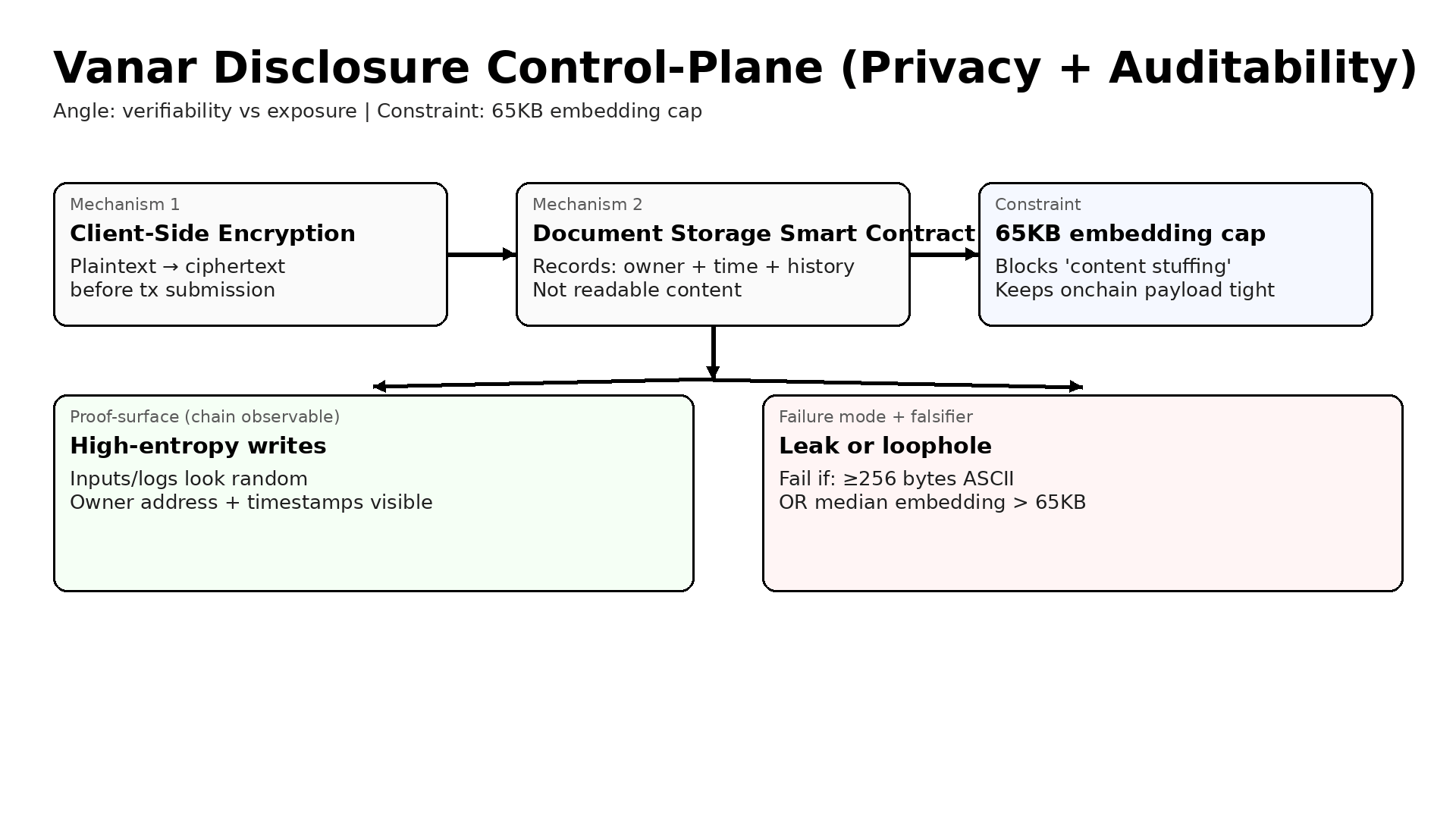

In Vanar’s approach, on Vanar Mainnet the first move is to encrypt on the user side before anything becomes a transaction. That is the core of Client-Side Encryption. The user’s device turns the content into ciphertext, not a readable blob, before anything is sent to the network. Then the Document Storage Smart Contract acts like a registry and a history log. It can record ownership and time and change history, while the content itself stays unreadable to everyone who does not hold the right key.

That split is the trade. You give up full onchain content availability. You cannot point any random tool at the chain and read the documents. You also accept a constraint that is not optional. The system caps AI embeddings, meaning a compact numeric summary used for search and reasoning, at 65KB per document. That limit forces discipline. You cannot quietly stuff large raw text into the “AI part” and pretend it is not content. If you want more, you need a different structure. That is not always convenient, but it is clear.

When people hear this, they sometimes say it sounds like hiding data. I do not see it that way. I see it as separating proof from payload. Proof is about a stable, verifiable history. Payload is the private thing you do not want to broadcast. In day to day product work, those are often mixed, and that is where risk lives. If you can keep proof public and payload private, you can build features that would otherwise stay stuck in legal review.

I like to explain it with a small personal test I ran while reading transactions in an explorer. When you look at an app that stores text onchain, you can often see readable strings in the input or logs. Even if it is not full text, there are hints. Names. IDs. Email like fragments. That is a disclosure leak, even if the app did not mean it. With the design here, the proof surface looks different. Registration and history writes look like random bytes, and you can sanity-check that by scanning the input or logs for long runs of readable characters. They still tie back to an owner address, and you can still see when the record was created and when it was updated. You can watch the history without seeing the content.

The 65KB embedding cap also creates a second signal that is easy to reason about. If a system is honest about its privacy boundary, you should not see big data pushes that look like someone is dumping a whole file into a transaction. You should see a tight size band around what the system allows. In other words, the chain should show a pattern, not a mess. For teams that care about compliance, patterns are comfort. You can explain them. You can monitor them. You can set alarms on them.

This angle matters because mainstream apps usually bring more sensitive data, not less. Games, entertainment, and brands all deal with identity, purchase history, access rights, and customer support artifacts. Even when you think it is not sensitive, it often becomes sensitive when combined with other data. If your audit story relies on publishing raw content, you are betting that no one will ever regret it. That is not a bet I would take.

The failure mode is also simple, which is good. The system fails if plaintext starts leaking into the chain path, or if the embedding path becomes a loophole for stuffing content onchain. Leaks can happen because a developer logs a field in the wrong place, or because a tool accidentally includes raw strings in a transaction. The embedding loophole can happen because teams love shortcuts. They will try to pack more context to get better results, even if that context is basically the document again. The cap is supposed to block that, but the only way it matters is if it is enforced and observed.

This is why I think the belief “auditability requires public data” is mispriced. It overpays for exposure and underpays for control. A disclosure control plane is not about hiding. It is about choosing what is provable in public and what must stay private for a real product to exist. When I picture that brand team trying to ship in a strict market, I can feel the difference in the room. They do not want philosophy. They want a clean rule they can say with a straight face to compliance and customers. “We can prove the timeline, but we do not publish the document.” That sentence changes what is possible.

If any registration or history transaction includes at least 256 bytes of printable ASCII in its input or logs, or if the median onchain embedding bytes per registration exceed 65KB, the claim fails.