When I hear “users can pay fees in SPL tokens,” my reaction isn’t excitement. It’s relief. Not because it’s novel, but because it finally admits something most systems quietly ignore: making users acquire a specific gas token is an onboarding tax that has nothing to do with the thing they actually came to do. It’s logistics. And forcing users to personally manage logistics is one of the fastest ways to make a good product feel broken.

So yes, this is a UX shift. But the more important change is where responsibility lives.

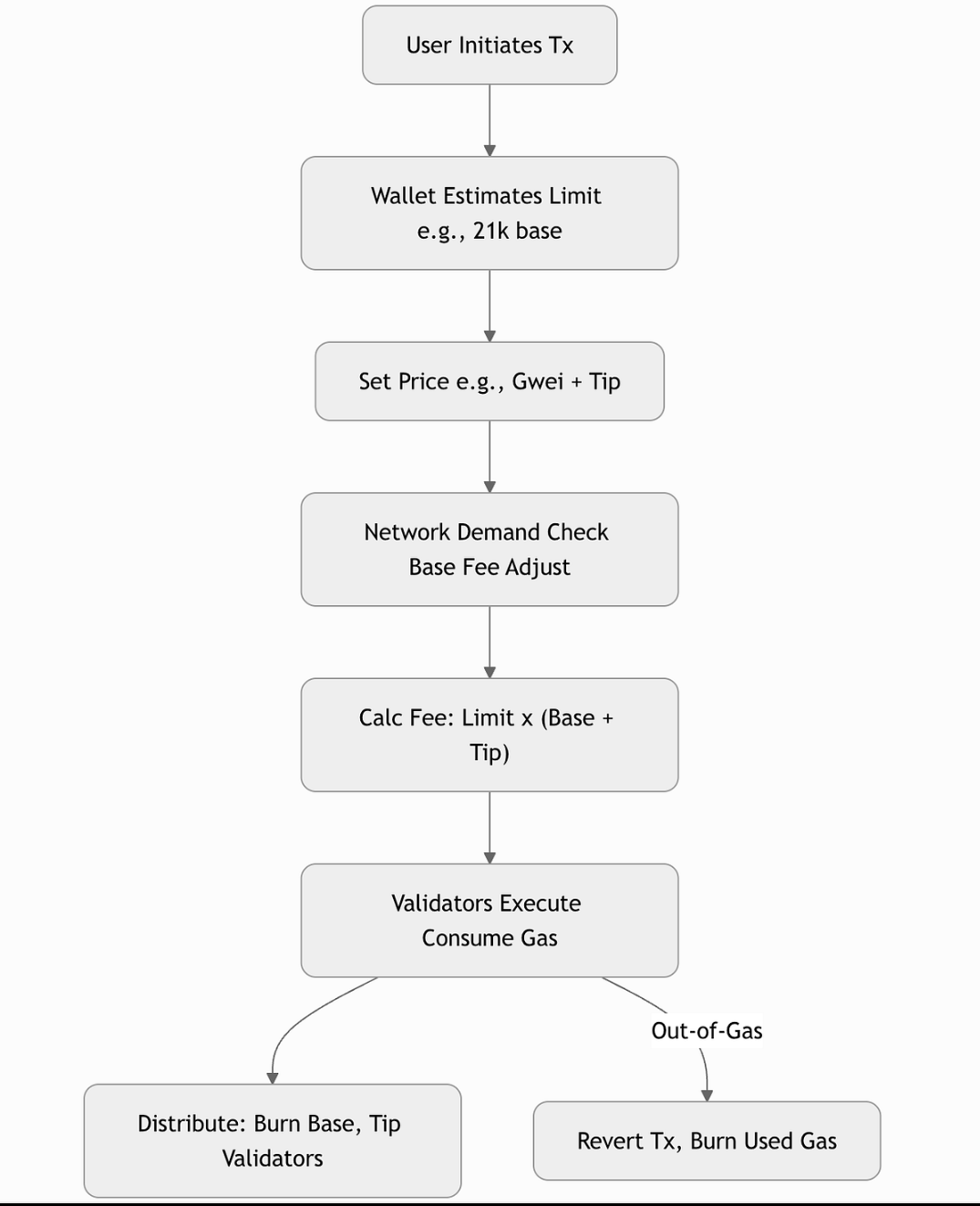

In the traditional model, the chain makes the user the fee manager. Want to mint, swap, stake, vote—do anything at all? First, go acquire the correct token just to be allowed to press buttons. If you don’t have it, you don’t get a normal product warning. You get a failed transaction, an opaque error, and a detour that makes people question whether the whole system is worth the effort. That isn’t a learning curve. It’s friction disguised as protocol purity.

Fogo’s move to SPL-based fee payment quietly flips this dynamic. The user stops being the one who has to plan for fees. The application stack takes that burden on. And once you do that, you’re making a decision that’s much bigger than convenience: you’re embedding a fee-underwriting layer into the default user experience.

Fees don’t vanish. Someone still pays them. What changes is who fronts the cost, who recovers it, and who sets the rules along the way.

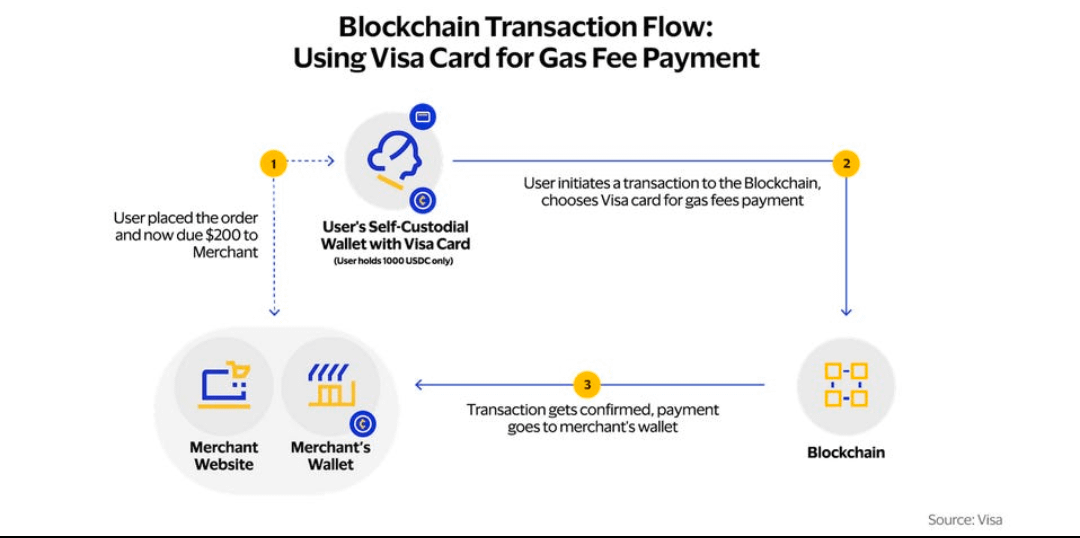

If a user pays in Token A but the network ultimately settles fees in Token B, there’s always a conversion step somewhere—even if it’s hidden. Sometimes it’s an on-chain swap. Sometimes it’s a relayer accepting Token A, paying the network fee, and reconciling later. Sometimes it’s inventory management: holding a basket of assets, netting flows internally, hedging exposure when needed. Regardless of the mechanism, it creates a pricing surface that suddenly matters a lot.

What rate does the user effectively get at execution time? Is there a spread? Who controls it? How does it behave under volatility?

That’s where the real story is. Not “you can pay in SPL tokens,” but “a new class of operator is now pricing your access to execution.”

This is why the “better onboarding” framing feels incomplete. Better onboarding is the visible effect. The deeper change is market structure. In native-gas-only systems, demand for the fee token is diffuse. Millions of small balances. Constant micro top-ups. Constant tiny failures when someone is short by a few cents. It’s messy, but it’s distributed.

With SPL-denominated fee flows, demand becomes professionalized. A smaller group of actors—paymasters, relayers, infrastructure providers—end up holding the native fee inventory and managing it like working capital. They don’t top up; they provision, rebalance, and defend against risk. That concentrates operational power in ways people tend to overlook until stress reveals it.

And stress always reveals it.

In a native-gas model, failure is usually local. You personally didn’t have enough gas. You personally set the wrong priority fee. It’s frustrating, but legible. In a paymaster model, failure modes become networked. The paymaster hits limits. Accepted tokens change. Spreads widen. Services go down. Oracles lag. Volatility spikes. Abuse protections trigger. Congestion policies shift. The user still experiences it as “the app failed,” but the cause lives in a layer most users don’t even know exists.

That isn’t inherently bad. In many ways, it’s the right direction. But it means trust moves up the stack. Users won’t care how elegant the architecture is if their experience depends on a small number of underwriting endpoints behaving correctly when conditions are ugly.

There’s another subtle shift that’s easy to miss. When you reduce repeated signature prompts and enable longer-lived interaction flows, you’re not just smoothing UX—you’re changing the security posture of the average user journey. You’re trading frequent explicit confirmation for delegated authority. Delegation can be safe if it’s tightly scoped, but it raises the cost of bad session boundaries, compromised front-ends, and poorly designed permission models.

So I don’t ask whether this is convenient. Of course it is. The question is who is now responsible for abuse prevention, limit setting, and guardrails—without turning the product back into friction.

Once apps decide how fees are paid, they inherit the user’s expectations. If you sponsor or route fees, you don’t get to point at the protocol when something breaks. From the user’s perspective, there is no separation. The product either works or it doesn’t. Fees become part of product reliability, not just protocol mechanics.

That’s where a new competitive surface opens up.

Applications won’t just compete on features. They’ll compete on execution quality: success rates, cost predictability, transparency around limits, responsiveness to edge cases, and behavior during chaotic markets. The apps that feel “solid” will be the ones backed by underwriting layers that are disciplined, conservative, and boring in the best possible way.

If you’re thinking long-term, the interesting outcome isn’t that users stop buying the gas token. It’s that a fee-underwriting market emerges, and the best operators quietly become default rails for the ecosystem. They’ll influence which assets are practically usable, which flows feel effortless, and which products feel fragile.

That’s why this feels strategic rather than cosmetic. It’s a chain choosing to treat fees as infrastructure—something specialists manage—rather than a ritual every user must perform. It’s an attempt to make usage feel normal: you arrive with the asset you already have, you do the thing you intended to do, and the system handles the plumbing.

The conviction thesis is simple. The long-term value of this design will be decided under stress. In calm markets, almost any fee abstraction looks good. In volatile, adversarial, congested conditions, only well-run underwriting systems continue to function without quietly taxing users through spreads, sudden restrictions, or unreliable execution.

So the real question isn’t “can users pay in SPL tokens?” It’s “who underwrites that promise, how do they price it, and what happens when conditions get ugly?”