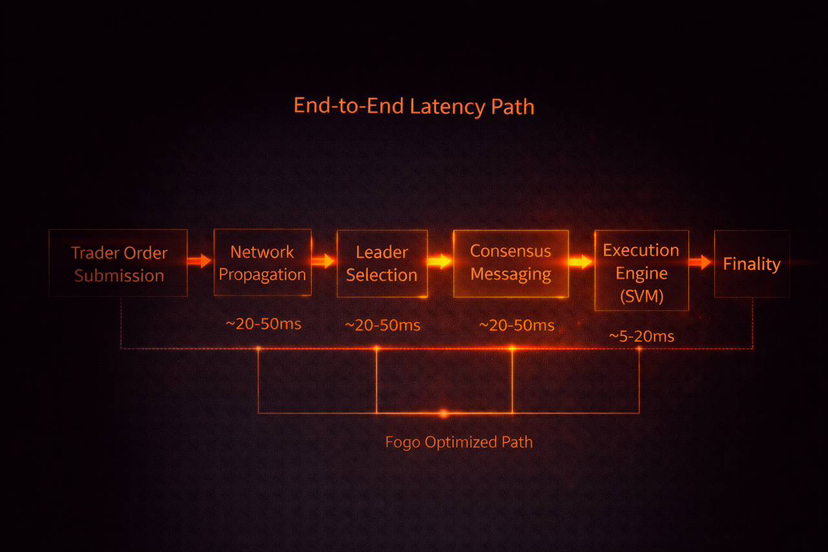

When I studied Fogo, the first thing I noticed is that it treats distance as a real cost, not a poetic idea. Most chains talk about decentralization as if every millisecond is the same everywhere. Fogo starts from the trader’s view of the world where a late message can be as damaging as a wrong message. The design is not only about pushing more transactions. It is about making transaction timing feel consistent, especially when markets get noisy and everyone rushes to the same block at the same time.

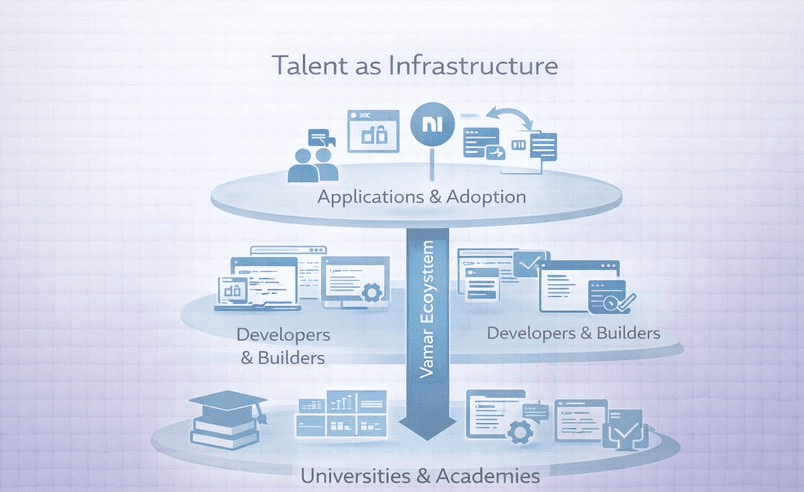

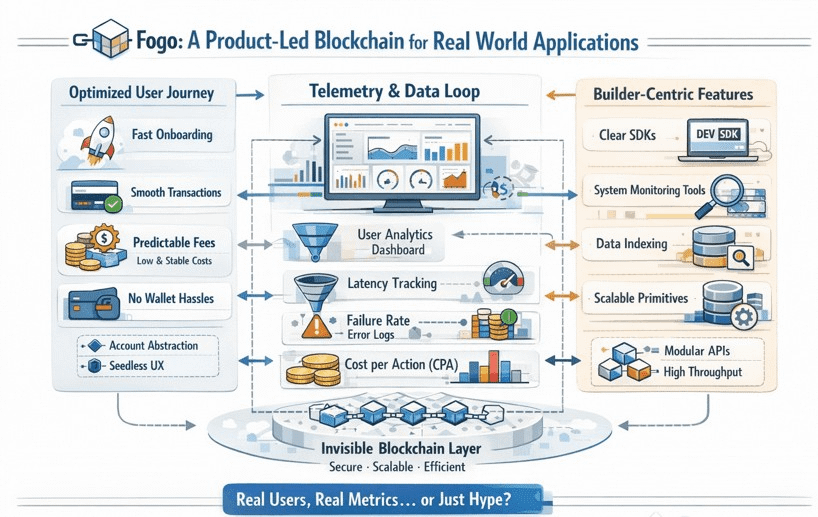

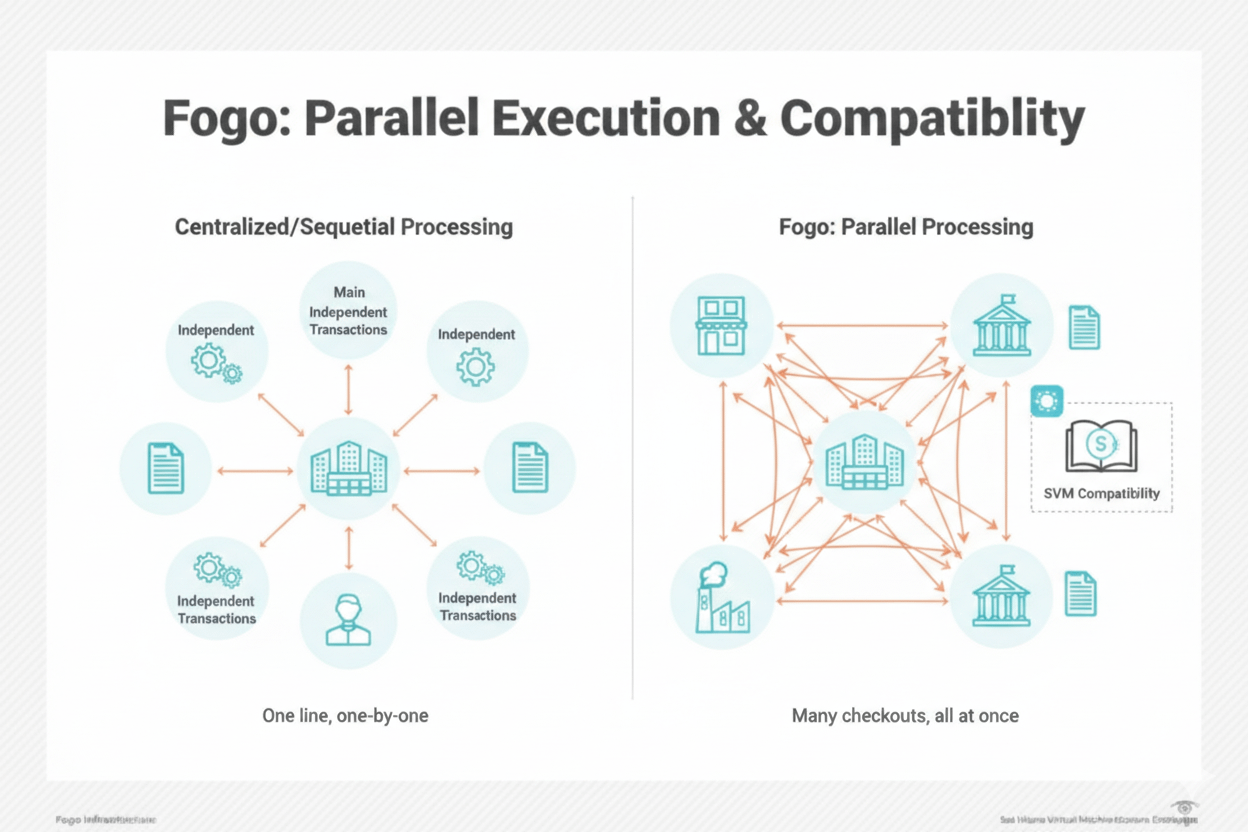

Fogo is a Layer 1 that uses the Solana Virtual Machine, so it inherits an execution environment that is already built around parallelism and high throughput. That matters because developers do not have to re learn basic assumptions about accounts, programs, and the way state is read and written. If you have built in the Solana style world, the mental model transfers: programs compiled to eBPF, accounts as first class state containers, and a runtime that can execute many non conflicting operations at once. This is the practical gift of SVM compatibility. You can keep your tooling, much of your code structure, and your performance instincts, instead of starting over on a new virtual machine with new limits and new edge cases.

But I also noticed a second point that matters just as much: compatibility is not dependency. Fogo is not borrowing Solana’s network state. It is not waiting for Solana’s leaders, Solana’s slots, or Solana’s fee market to decide what happens next. It runs its own validator set, its own consensus votes, and its own parameter choices. That independence is the difference between living in the same language and living in the same house. If Solana has congestion, governance drama, or outages, a separate chain does not magically avoid all problems, but it is not mechanically forced to inherit them either. The tradeoff is that liquidity and social gravity do not automatically come with you. You have to earn them through bridges, listings, and ecosystem pull. Fogo is basically saying: I want the SVM developer experience, but I want to control my own performance envelope.

This is where Multi Local Consensus becomes the center of the story. In plain words, Multi Local Consensus is a way to run a fast agreement process by letting the active validators sit close together in a physical sense, then rotate that active location over time so the network is not permanently tied to one place. Fogo calls these physical groupings zones, and the ideal zone is tight enough that network latency between validators approaches hardware limits, which is why the docs talk about zones being a single data center in the best case.

To see why this matters, I like to picture a classic globally distributed validator set. If validators are spread across continents, the speed of consensus is controlled by the slowest paths and by variance, not the average. Even if most validators can talk quickly, a few long distance links stretch the round trips needed for proposals and votes. Under load, variance gets worse. Suddenly the chain does not only slow down, it becomes unpredictable. Blocks come in bursts, confirmations feel uneven, and latency sensitive apps start acting like they are running on a shaky clock.

Multi Local Consensus attacks that variance directly. When validators that actively produce blocks and vote are co located within one zone for an epoch, the consensus messages travel shorter paths with tighter timing. Instead of fighting physics, the protocol leans into it. The goal is not only lower latency, but lower latency variance, which is what makes performance feel deterministic. When I say deterministic here, I do not mean mathematically perfect. I mean you can design an on chain order book, a liquidation engine, or an auction with fewer ugly surprises, because your confirmation time distribution has a shorter tail.

The white paper describes Fogo as a Byzantine fault tolerant proof of stake system optimized for extremely low latency, with stake weighted voting and validators that can be co located in zones to minimize round trip network latency. It also describes block production by a leader appointed by a deterministic, stake weighted schedule, with parameters decided per epoch via validator voting. That set of ideas is familiar if you have lived near Solana style consensus, but the twist is how explicitly locality becomes part of the operating model.

Under the hood, Fogo’s validator software is based on Firedancer, and the white paper notes that the current implementation at launch includes portions of Agave code, described there as Frankendancer, with Fogo specific modifications. In practice, this is the part that tries to squeeze every microsecond out of networking and execution so that the consensus design has a chance to shine. Multi Local Consensus without an aggressively optimized client would still be limited by software overhead. The client and the locality model are meant to work together: fast packet handling, fast verification, fast state access, and fast propagation inside the zone.

Now let me break down the zone idea in simple operational terms, the way I would explain it to a builder. Imagine the chain has many validators around the world, but it chooses a subset that will be active in the next epoch, and that subset is designed to run in one tight region. They agree on who leads which slots and how they vote. Because their physical distance is small, block proposals and votes circulate quickly and consistently. Meanwhile, other nodes outside the zone can still run full nodes, observe the chain, relay data, and be ready for rotation. Over time, the active zone can rotate to another region to spread operational control and reduce the feeling that one geography owns the chain’s heartbeat. The white paper explicitly mentions coordinated geographic zones and the ability to rotate zones between data centers globally to maintain geographic decentralization and operational resilience.

That rotation is important because locality is a trade. You are buying performance by reducing dispersion during the most latency sensitive part of consensus. If you never rotate, you risk building a chain that is fast but socially and politically stuck in one physical jurisdiction and one data center ecosystem. If you rotate too aggressively, you risk introducing churn, operational mistakes, and a new kind of instability where every epoch transition is a performance cliff. The whole art is finding a cadence that keeps performance steady while still letting the network move.

When Fogo talks about zones reducing latency variance, it is basically saying: most of the ugly behavior traders hate is not average latency, it is jitter. Jitter is what turns a fair auction into a game of timing luck. Jitter is what makes liquidations unpredictable. Jitter is what makes market makers pull liquidity because they cannot price risk. A zone with co located validators compresses jitter. In that world, block times can be pushed lower, but more importantly, the system is less likely to hit long stalls caused by cross ocean message delays. The docs even frame zones as the way to enable ultra low latency consensus, mentioning block times under 100 ms as an architectural target.

Finality in this design is best thought of as fast voting convergence. In a BFT proof of stake system, blocks become final when a supermajority of stake has voted in a way that locks in the history, and later votes build on top of it. Locality does not change the mathematics of Byzantine fault tolerance, but it changes the timing behavior of the vote propagation that makes finality feel smooth. When the validators that matter are close, the time between proposal and vote aggregation shrinks, and the distribution tightens. That is why I keep coming back to deterministic performance as a feeling. Builders and traders can plan around a tighter window.

Throughput is the other half of the equation, and here SVM compatibility matters again. The Solana style account model and parallel execution mean you can process many transactions simultaneously as long as they are not fighting over the same state. The white paper highlights horizontal account database scalability similar to Solana’s account model, which is a fancy way of saying the chain is designed so large applications can read and write state concurrently without every action becoming a single file line at the bank. For structured markets, this matters. An order book can update many users’ balances and positions in parallel if the program and state layout are designed well. A derivatives venue can process funding payments, trades, and risk checks without turning into a single threaded bottleneck.

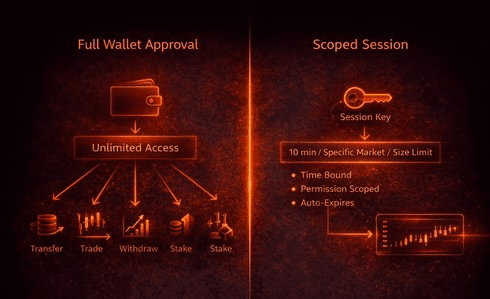

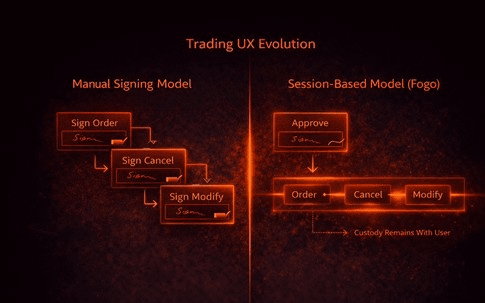

If you are building latency sensitive DeFi, you also care about how transactions are ordered under contention. The white paper states that the client software is designed to support validators ordering transactions by priority fees, meaning higher priority fee transactions are processed first when a validator assembles a new block, and that priority fees accrue directly to the validator producing that block. This is an honest statement: when demand spikes, the chain uses an economic signal to decide what goes first.

This ordering policy is both a tool and a risk. It is a tool because it gives urgent actions a way to express urgency. Liquidations, arbitrage rebalances, and risk reducing trades can pay more to be included sooner. It is a risk because it can amplify MEV and fairness problems. If validators have discretion, sophisticated actors will try to shape ordering beyond simple fee bidding. They will bundle, back run, and build strategies that extract value from slower users. A zone based design can even intensify parts of this, because when performance is more predictable, professional searchers can time actions more precisely. So the chain has to think hard about what rules it enforces, what it leaves to validators, and how it monitors behavior.

Token utility in Fogo is kept fairly straightforward in the documents, and I appreciate that simplicity. The token is used to pay for transaction and storage costs, and it is the collateral for validators in the proof of stake system. Validators and delegators receive rewards proportional to stake and performance, drawn from token issuance and transaction fees, and validators can charge commissions on staking rewards. Priority fees go to the validator producing the block. In plain language, security comes from staked value that can be at risk, and liveness comes from the fact that validators are paid to keep producing and voting.

The inflation schedule is actually specified in the MiCA style white paper. It says the protocol is designed to issue new tokens at a fixed 6 percent annual inflation rate, decreasing linearly to 2 percent after two years via year on year decrements. I am not going to invent any extra numbers around supply or allocations here, but this schedule tells you the intended shape of incentives: early on there is more issuance to attract and pay validators, then the system aims to reduce dilution over time while keeping a long term floor for security rewards.

There is also an important operational detail hiding in plain sight: Fogo’s white paper notes that an audit is true but the audit report has not yet been issued because the process is ongoing. That matters because performance focused chains can ship fast, but the market eventually punishes unsafe code. If you are deploying serious capital, you want to see audits, bug bounty history, and incident response maturity, not just a benchmark chart.

Now, about recent updates with real dates, here is what I can ground in multiple sources. Several outlets report that Fogo launched its public mainnet on January 15, 2026, with coverage framing it as an SVM compatible Layer 1 aimed at on chain trading, and connecting the launch to a Binance token sale.

One of the more concrete historical anchors mentioned in reporting is that Fogo launched a testnet in July 2025. This point appears in coverage describing the testnet’s performance and lead up to mainnet.

There are also claims circulating in community style posts about tokenomics adjustments on January 12, 2026 and various performance numbers. Because some of those claims appear in user generated content streams rather than primary technical releases, I treat them as uncertain unless corroborated elsewhere. If you see a date attached to tokenomics changes or performance stats, it is worth cross checking against official documentation and on chain data before you rely on it for decisions.

With that grounded, I want to return to what kinds of applications actually benefit from this design. If you are building slow moving DeFi, like long term lending with low update frequency, you still benefit from cheap fees and solid throughput, but you do not need multi local consensus to sleep at night. The real beneficiaries are structured markets where microstructure matters. Real time trading venues, on chain order books, perps engines, auctions that clear frequently, and systems that manage risk continuously all suffer when chain latency is unpredictable. They suffer even more when latency is predictable for insiders but not for everyone else. Fogo is trying to push the base layer toward a world where on chain execution can be treated as a reliable clock, not a sometimes fast, sometimes frozen event stream.

Latency sensitive DeFi also includes things people forget, like settlement layers for market makers and routing layers for aggregators. If blocks arrive at a steady pace, a router can make better choices. If finality is smooth, market makers can tighten spreads because they can estimate inventory risk more accurately. If congestion behavior is controlled, liquidations can be designed with fewer emergency assumptions. These are not flashy features, but they are the infrastructure that makes trading feel boring, and boring is usually what serious liquidity wants.

Still, what could go wrong is not a footnote here. The first risk is centralization pressure through hardware and colocation requirements. If the best performance requires validators to run in specific high end data centers with specialized networking, you narrow the set of people who can realistically participate. Even if delegation is open to everyone, control still concentrates in the operators who can meet the operational bar. This is not automatically fatal, but it shifts decentralization from geography to organization. You have to be honest about that shift.

The second risk is zone curation risk. Somebody, or some governance process, decides what counts as a zone, which data centers are eligible, what the rotation policy is, and what performance parameters are acceptable. If this becomes political, zones could be curated to favor certain participants or jurisdictions. If it becomes too rigid, the chain could be stuck in a small club of validators who always meet the requirements. If it becomes too loose, you lose the performance stability that justified the design. The rotation mechanism is a governance and operations problem disguised as a consensus feature.

The third risk is MEV and fairness. Priority fees and validator discretion can create a market for inclusion, but they can also create a market for manipulation. In fast deterministic environments, sophisticated actors get sharper tools. If the protocol does not build guardrails, you may end up with a chain that is excellent at executing, but also excellent at extracting. Then users will ask the hardest question: fast for whom.

The fourth risk is governance tradeoffs around parameter tuning. The white paper suggests that within a zone, block times and performance parameters can be dynamically tuned and decided per epoch via validator voting. That is flexible, but flexibility can become a governance attack surface. If parameters can be changed quickly, they can also be captured quickly. If they cannot be changed quickly, you may not adapt to new network realities. Again, the theme is that physical reality forces explicit choices, and explicit choices create politics.

The last risk is resilience under partial failure. A zone is a powerful performance engine, but zones are still physical places. Data centers can have outages, routing incidents, or coordinated attacks. The promise of rotating zones and having full nodes in alternate data centers is part of the resilience story, but execution under stress is what proves the design. A zone based system needs clean failover procedures and clear rules for what happens when the zone is degraded, otherwise deterministic performance turns into deterministic downtime.

After sitting with all this, I come away thinking Fogo is less about chasing a bigger number and more about respecting the shape of time. The SVM layer gives builders a familiar, high throughput runtime, but Multi Local Consensus is the bet that physical placement can make on chain markets feel more like engineered systems and less like weather. If this approach works, it could make a future where order books, auctions, and risk engines live fully on chain without apologizing for their own clock. If it fails, it will probably fail in the hard human places: who gets to be close, who decides where close is, and how you keep speed from becoming privilege. Either way, the idea that consensus can be physically aware feels like a documentary turning point to me, because markets have always been about information moving through space, and blockchains are finally starting to admit that space never stopped mattering.