When I first started thinking seriously about Walrus’s availability proofs, my instinct was the same as many engineers in this space: why not use zero-knowledge proofs? zk-SNARKs and zk-STARKs have become almost reflexive answers to questions about privacy and scalability. They promise smaller proofs, cheaper verification, and strong cryptographic guarantees.

But the more I sit with the design goals of Walrus, the more I realize that this question isn’t about whether zk-proofs are possible. It’s about whether they are appropriate, timely, and aligned with the realities of decentralized storage.

This article is my attempt to think through that question carefully—not as a roadmap promise, but as an architectural exploration.

What Walrus Is Actually Proving Today

Before we talk about zk-SNARKs or zk-STARKs, it’s important to be precise about what Walrus proofs are doing today.

Walrus is designed to ensure data availability, not data secrecy. Its proofs are meant to answer a simple but critical question: Is the data still retrievable, even if some storage nodes fail or go offline?

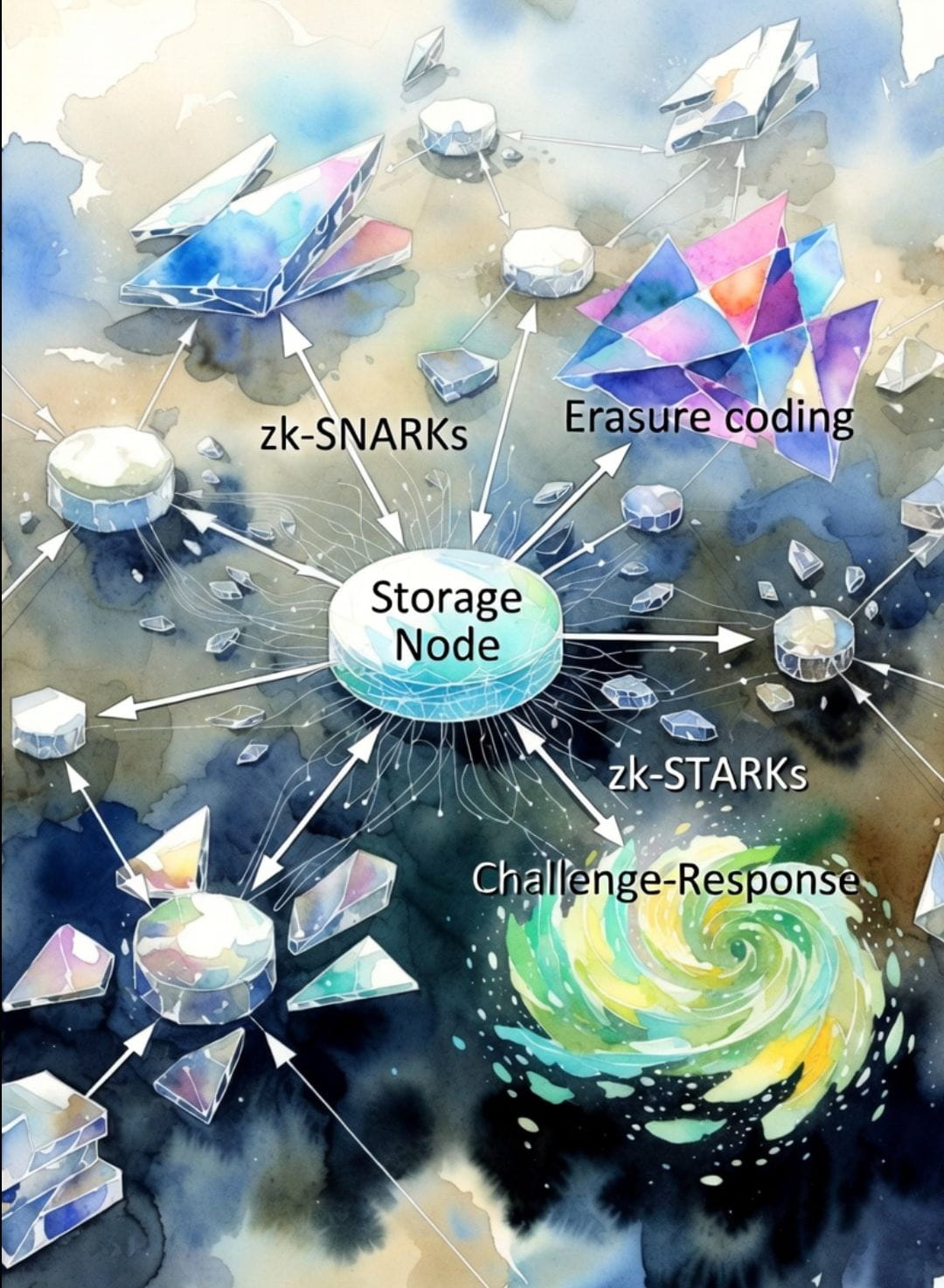

To achieve this, Walrus relies on erasure coding, redundancy, and challenge-response mechanisms. Storage nodes periodically demonstrate that they still possess their assigned data fragments and can serve them when requested.

These proofs are then anchored on Sui, where they become economically enforceable. The chain does not need to know the data itself—it only needs enough information to confirm that availability guarantees are being upheld.

This distinction matters, because zk-proofs shine in environments where privacy of computation is essential. Walrus, by contrast, is optimizing first for verifiability and liveness.

Where zk-Proofs Could Fit Conceptually

That said, zk-SNARKs and zk-STARKs are not irrelevant to Walrus. In theory, they could be used in two main areas:

1. Compressing availability proofs

Instead of submitting multiple on-chain attestations, a storage node (or aggregator) could submit a single succinct proof that many checks were performed correctly.

2. Hiding operational details

Proofs could conceal which exact fragments were challenged, which nodes responded, or how redundancy was structured—while still proving that protocol rules were followed.

From a purely cryptographic standpoint, both zk-SNARKs and zk-STARKs are capable of expressing these statements.

The harder question is whether doing so improves the system in practice.

Verification Cost vs. Proof Generation Cost

One of the main motivations for zk-proofs is reducing on-chain verification cost. This is especially relevant on execution layers where gas efficiency matters.

But Walrus operates in a more nuanced cost environment.

On-chain verification on Sui is already relatively efficient, especially when proofs are simple and parallelizable. Introducing zk-proofs would reduce verification steps, but it would also increase off-chain computation significantly.

For storage nodes, proof generation is not free. zk-SNARKs require trusted setups and heavy computation; zk-STARKs avoid trusted setups but produce larger proofs and still require substantial resources.

In a storage network, where margins are already tight, pushing expensive cryptographic workloads onto storage providers could unintentionally bias participation toward larger operators. That would work against Walrus’s decentralization goals.

So while zk-proofs may reduce on-chain cost, they risk increasing centralization pressure off-chain.

Privacy: Is It Actually a Priority for Availability Proofs?

Another reason zk-proofs are often proposed is privacy. And here, it’s worth being honest: data availability proofs are not inherently privacy-sensitive.

Walrus does not reveal user data on-chain. It does not expose file contents, nor does it require nodes to publish raw fragments. What’s visible is that some proof was submitted, and some condition was met.

In many cases, that level of transparency is not a bug—it’s a feature. Availability systems benefit from observable behavior. Auditors, developers, and even users can reason about system health precisely because proofs are legible.

Introducing zero-knowledge could obscure useful signals without delivering proportional benefits. Privacy is powerful, but only when it protects something that truly needs protection.

zk-Proofs and the Challenge of Liveness

One subtle but important point is that availability is a liveness property, not just a correctness property.

zk-proofs excel at proving that something was computed correctly. They are less naturally suited to proving that something remains accessible over time. Availability proofs are inherently temporal—they need to be repeated, challenged, and refreshed.

Encoding liveness into zk-circuits is possible, but it adds complexity. The system must define what “availability over time” means in circuit terms, and that definition must evolve as network conditions change.

Walrus’s current proof model is intentionally flexible. It can adjust challenge frequency, redundancy thresholds, and slashing logic without redesigning cryptographic circuits. zk-based systems are far less forgiving in this regard.

Is Walrus Exploring zk-Based Proofs?

From a design-research perspective, it would be surprising if zk-based approaches were not being explored at least experimentally. Any serious protocol team evaluates emerging cryptographic tools.

But exploration does not equal adoption.

In Walrus’s case, zk-SNARKs or zk-STARKs are more likely to appear first in auxiliary roles—for example, in aggregated reporting, auditing layers, or optional privacy-preserving modules—rather than replacing the core availability proof mechanism.

That kind of incremental integration aligns better with Walrus’s engineering philosophy: evolve cautiously, preserve system clarity, and avoid premature complexity.

zk-SNARKs vs. zk-STARKs: A Brief Comparison in Context

If Walrus were to experiment with zk-proofs, the choice between SNARKs and STARKs would matter.

zk-SNARKs offer smaller proofs and faster verification, but often rely on trusted setups and elliptic curve assumptions. zk-STARKs avoid trusted setups and are more transparent, but their proofs are larger and verification costs can be higher.

Given Walrus’s emphasis on neutrality and long-term robustness, STARK-based approaches would likely align better philosophically. But again, that alignment must be weighed against real-world performance and operator constraints.

A Broader Design Philosophy at Work

What this discussion really highlights is Walrus’s broader design stance: don’t optimize cryptography in isolation.

Availability systems sit at the intersection of economics, networking, and cryptography. A proof that is elegant on paper but costly in practice can destabilize incentives. A privacy feature that obscures accountability can weaken trust.

Walrus appears to prioritize comprehensible security—systems that developers and operators can reason about without becoming cryptography specialists. That choice may feel conservative, but it has practical advantages.

Final Reflection

So, could Walrus’s availability proofs be generated using zk-SNARKs or zk-STARKs?

Yes, in theory.

Is it being explored?

Almost certainly at a research level.

Is it obviously the right move today?

That’s far less clear.

From where I stand, the most responsible path is cautious experimentation, not wholesale replacement. zk-proofs are powerful tools, but they are not universal solutions. Walrus’s current proof model is transparent, adaptable, and well-matched to its core mission.

Sometimes the most advanced system is not the one using the newest cryptography, but the one that understands exactly why it uses what it does.

And in decentralized storage, that kind of restraint may be the strongest proof of all.