@Walrus 🦭/acc In crypto, “data availability” can sound like a background detail until the moment it fails. Then it stops being philosophy and turns into a very practical question: can anyone actually retrieve the data they’re expected to verify, or are we just pointing at a hash and pretending that’s enough? Walrus Protocol treats availability as an engineering promise: large files should stay recoverable and checkable even when storage nodes churn, go offline, or act in bad faith.

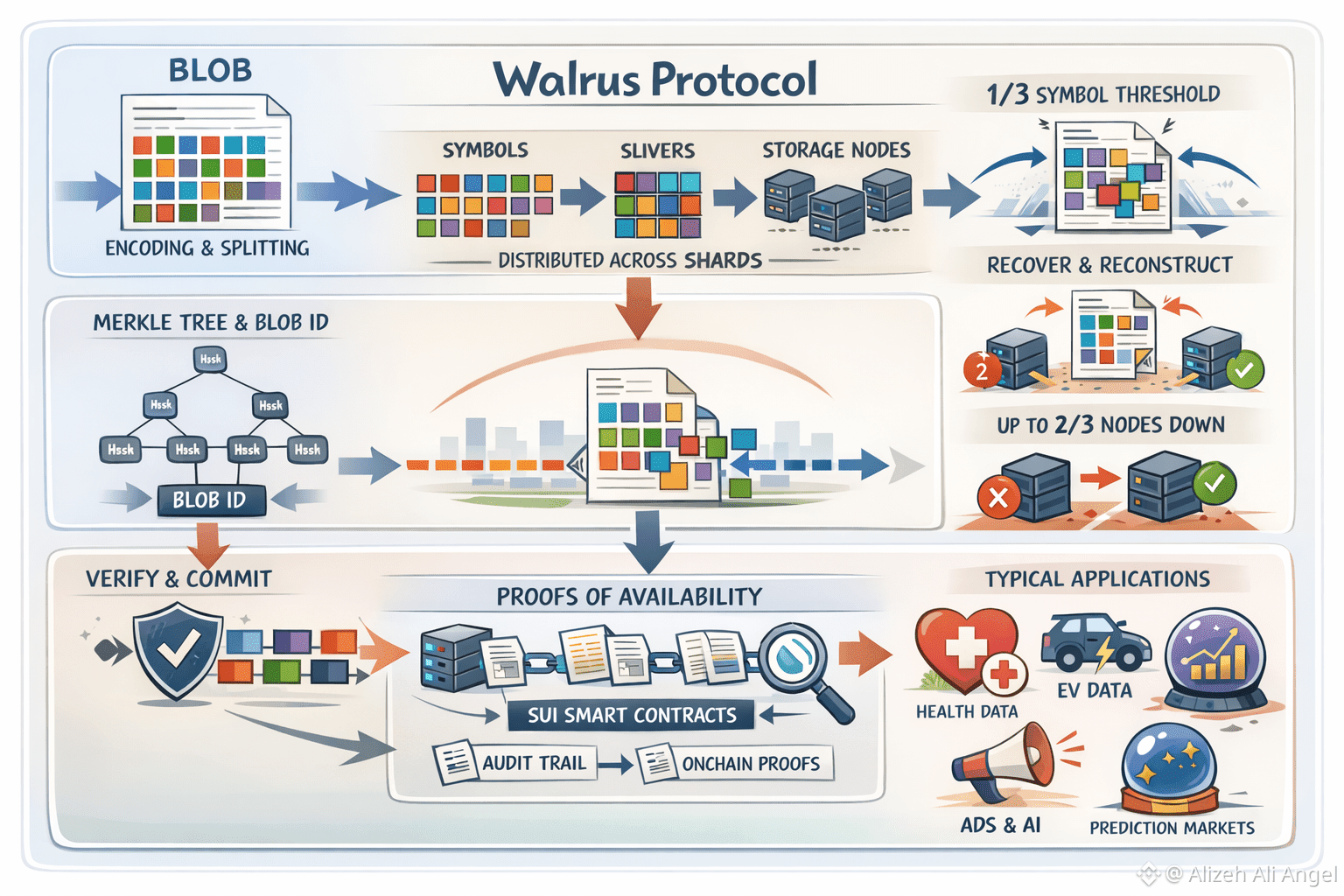

Walrus starts by refusing the most expensive default in blockchains: making everyone store everything. Instead, it encodes a file (a “blob”) into many smaller pieces and spreads them across the network. The language Walrus uses here matters because it’s concrete. A blob is split into symbols, symbols are bundled into “slivers,” and slivers are assigned across shards that storage nodes manage. The payoff is a clear threshold: Walrus can reconstruct a blob from just one-third of the encoded symbols, which is a different mental model than “hope the right server is up.”

The trade-off, of course, is overhead. Availability is never free; it’s purchased with redundancy. Walrus is explicit that encoding expands the blob size by roughly 4.5–5×, and that this expansion doesn’t depend on how many shards or storage nodes exist. That last clause is easy to miss, but it’s important. It means the resilience target is baked into the scheme rather than negotiated every time the network grows.

Still, availability without correctness is a trap. If you can retrieve “something” but can’t prove it’s the intended data, you’ve just moved the trust problem around. Walrus addresses this with a straightforward authenticity story: each blob has a blob ID derived from hashes of shard data using a Merkle tree, so clients can verify what they receive against commitments. In plain terms, the system doesn’t just want you to fetch slivers; it wants you to be able to defend that the reconstructed blob matches what was originally stored.

This is where Walrus’s version of “data availability” gets more distinctive: it tries to make availability measurable, not vibes-based. Walrus pushes control-plane responsibilities onto Sui, so each stored blob is represented by an onchain object that carries identifiers, commitments, size, and storage duration. Proofs of Availability (PoA) are then submitted to Sui smart contracts as transactions, creating a public audit trail of whether the network is meeting its obligations. Importantly, Walrus frames this as chain-agnostic for builders: settlement happens on Sui, but the application consuming the data doesn’t have to live there.

Even the act of reading is treated as a resilience problem with explicit thresholds. Walrus’s own walkthrough describes clients collecting slivers from storage nodes, verifying them against commitments, and waiting until they reach a one-third quorum of correct secondary slivers. That lower read quorum—different from the higher quorum needed to write—means reads are designed to keep working through real-world messiness. The same piece also notes that blobs can still be recovered after synchronization even if up to two-thirds of nodes are unavailable, which is the kind of statement you can test rather than merely believe.

So why is this topic suddenly showing up everywhere? Part of it is the broader “separate the layers” mood in crypto: people are more comfortable splitting execution, settlement, and storage into different systems and then judging each one on its own failure modes. But the bigger driver feels cultural. Data now carries reputational and economic weight in a way it didn’t even two years ago. AI agents, health tech, ad verification, prediction markets—these are all domains where “trust me” data pipelines age poorly. Walrus itself highlights a wave of applications built in 2025 across health data, advertising data, EV data, and AI agents, which is a useful signal that “availability” is being pulled by demand, not just pushed by protocol designers.

There’s also genuine technical progress behind the narrative. Mysten Labs introduced Walrus publicly in 2024 as a decentralized storage and data availability protocol aimed at encoding large blobs into slivers that can be reconstructed even when many slivers are missing. The academic framing caught up in 2025 with the Walrus paper describing Red Stuff as a two-dimensional erasure coding protocol with a 4.5× replication factor, plus storage challenges that work in asynchronous networks (a subtle point that matters when attackers can exploit timing and network delays).

If you want a simple way to hold the idea in your head, try this: availability isn’t a switch, it’s a ladder. First rung: you can usually read quickly. Second rung: you can still reconstruct when parts of the network disappear. Third rung: you can prove, publicly, that the network met its obligations, and you have recourse when it didn’t. Walrus is interesting because it tries to build all three rungs into one coherent story—encoding for recovery, commitments for correctness, and onchain proofs for accountability—without asking every builder to become a storage engineer just to ship an app.