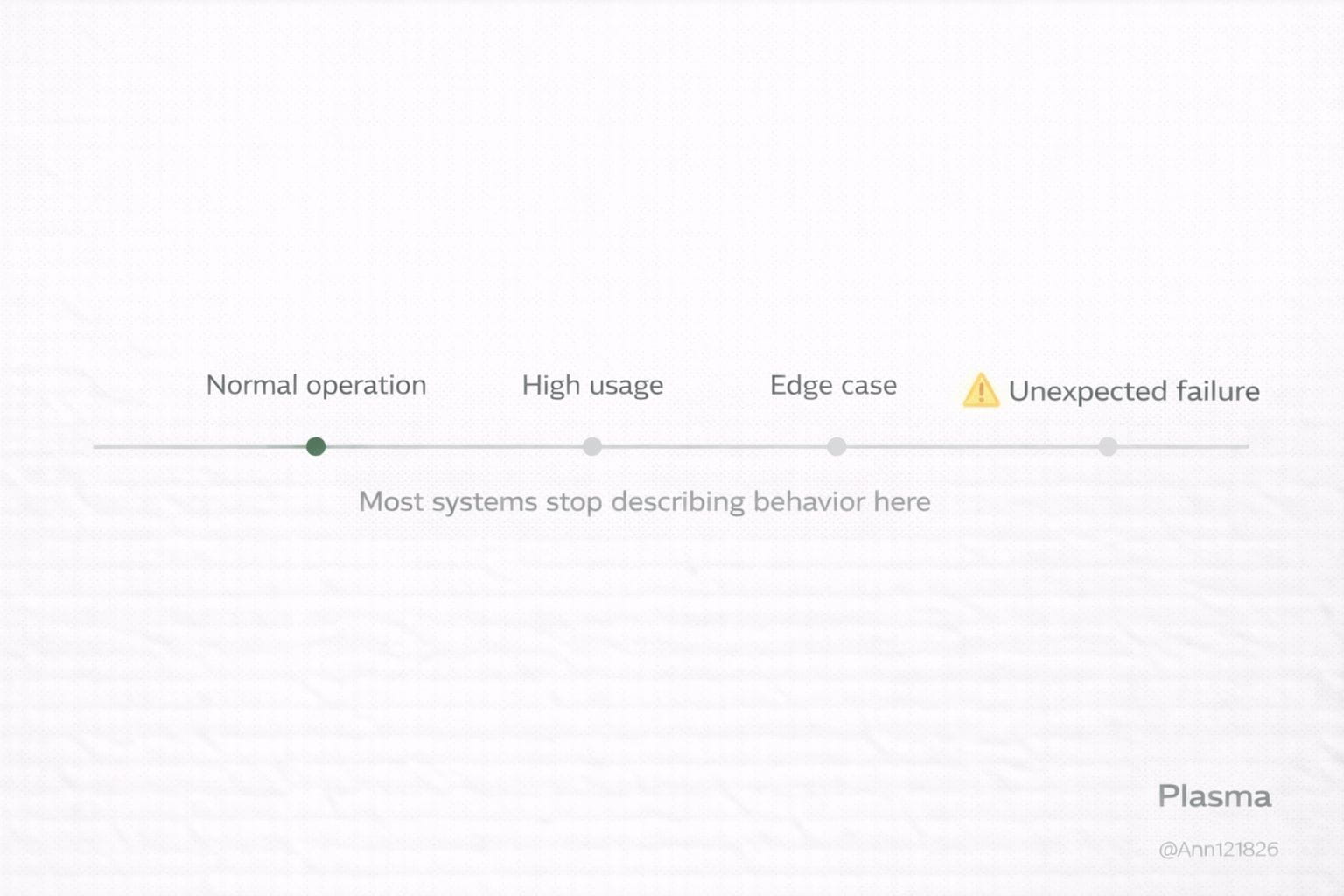

Most blockchains are designed to work well when everything is going fine. Valid transactions, honest users, aligned incentives, and load within expectations. In that scenario, almost any architecture seems sufficient. The problem arises when the system moves out of that ideal state and enters real conditions: errors, congestion, disputes, partial executions, or unexpected behaviors.

In financial infrastructures, failure is not an anomaly: it is a condition that must be anticipated. However, many on-chain networks treat failure as an external event, something that will be resolved "later" through governance, social coordination, or manual intervention. The result is a critical void: when something fails, no one can accurately anticipate what happens or who takes responsibility.

Plasma starts from a different premise. If a network is designed to move value, it must explicitly define how it behaves not only when everything works, but also when something breaks. It is not enough for the system to be efficient under normal conditions; it must be understandable and bounded under failure. In finance, ambiguity during an error is a form of systemic risk.

Many general-purpose blockchains allow multiple interpretations when a problem occurs. Depending on the context, a transaction may be delayed, reverted, prioritized differently, or become subject to external decisions. Technically, the system continues to 'operate', but financially it ceases to be reliable. The fault lies not in the bug, but in the lack of clear rules about what happens next.

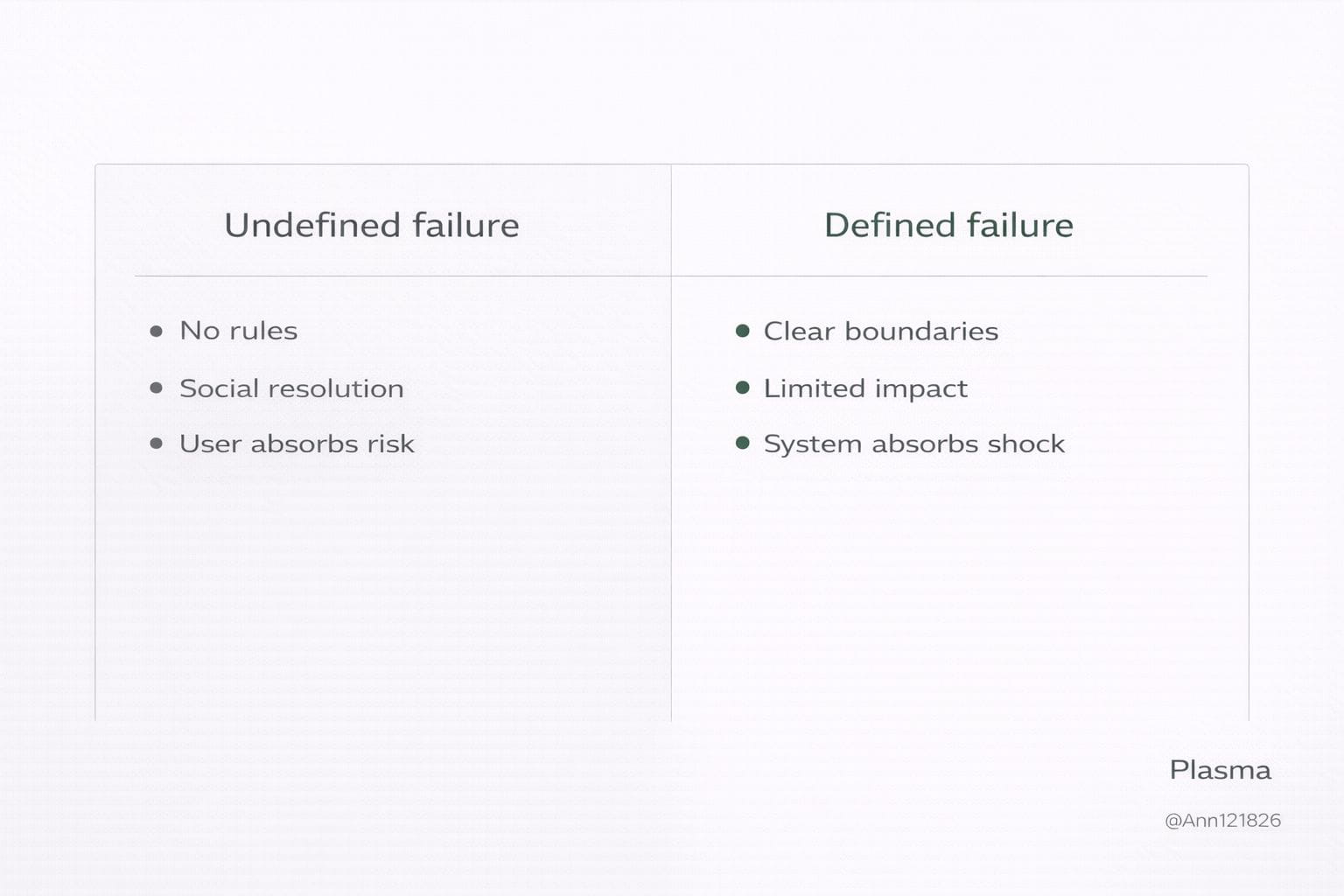

Plasma reduces that space of ambiguity. By limiting the possible states of the system, it also limits the failure scenarios. When an error occurs, the behavior is not negotiated or interpreted: it is defined by the infrastructure. This does not eliminate failures, but it does eliminate the uncertainty surrounding them. And in financial systems, knowing exactly how a network fails is as important as knowing how it works.

A simple example illustrates this. Two entities settle recurring payments on a general-purpose blockchain. One day, an unexpected congestion alters the order, timing, and priorities. The payment is not lost, but it does not occur as planned. Manual reconciliations, internal reviews, and discussions about responsibility arise. The technical system did not collapse, but the financial system did become fragile.

In Plasma, the same scenario is constrained from the design. The failure does not open new interpretations or alternative routes. The system always responds within a predefined framework, even under error. This does not make the network more expressive, but rather more usable for processes that cannot rely on exceptions.

This difference often goes unnoticed because it does not improve visible metrics like speed or flexibility. However, it defines whether an infrastructure can scale without accumulating hidden risk. Networks that do not design their own failure end up delegating it to external agreements, human operators, or improvised patches.

From a financial perspective, the maturity of an infrastructure is not measured by how well it works when everything goes well, but by how little it surprises when something goes wrong. In that sense, Plasma does not compete by promising ideal scenarios, but by eliminating uncertainty in real scenarios. Designing for failure is not technical pessimism; it is structural responsibility.