@Walrus 🦭/acc Lately I’ve noticed the way builders talk about storage is changing. It used to be a practical debate about where data sits and who controls it. Decentralized storage, in particular, was often framed as a safer alternative to the cloud—less lock-in, fewer single points of failure, maybe a better deal over time. But that isn’t the most interesting part anymore. The conversation is shifting toward what storage can actually do. The more interesting question now is whether storage can behave like a programmable part of an application—something you can compose with payments, permissions, and workflows—rather than a passive bucket you dump data into and pray you can retrieve later.

Walrus sits right in that change. It’s positioned as a decentralized storage and data availability protocol built for blockchain apps and autonomous agents, with a design that tries to keep costs reasonable while still staying robust as the network scales. And the Walrus Foundation’s RFP program is basically an admission that protocols don’t become real infrastructure on their own. Someone has to build the parts that make it feel normal to use: tooling, integrations, and the boring-but-essential connective tissue between a strong core and real developers shipping real products.

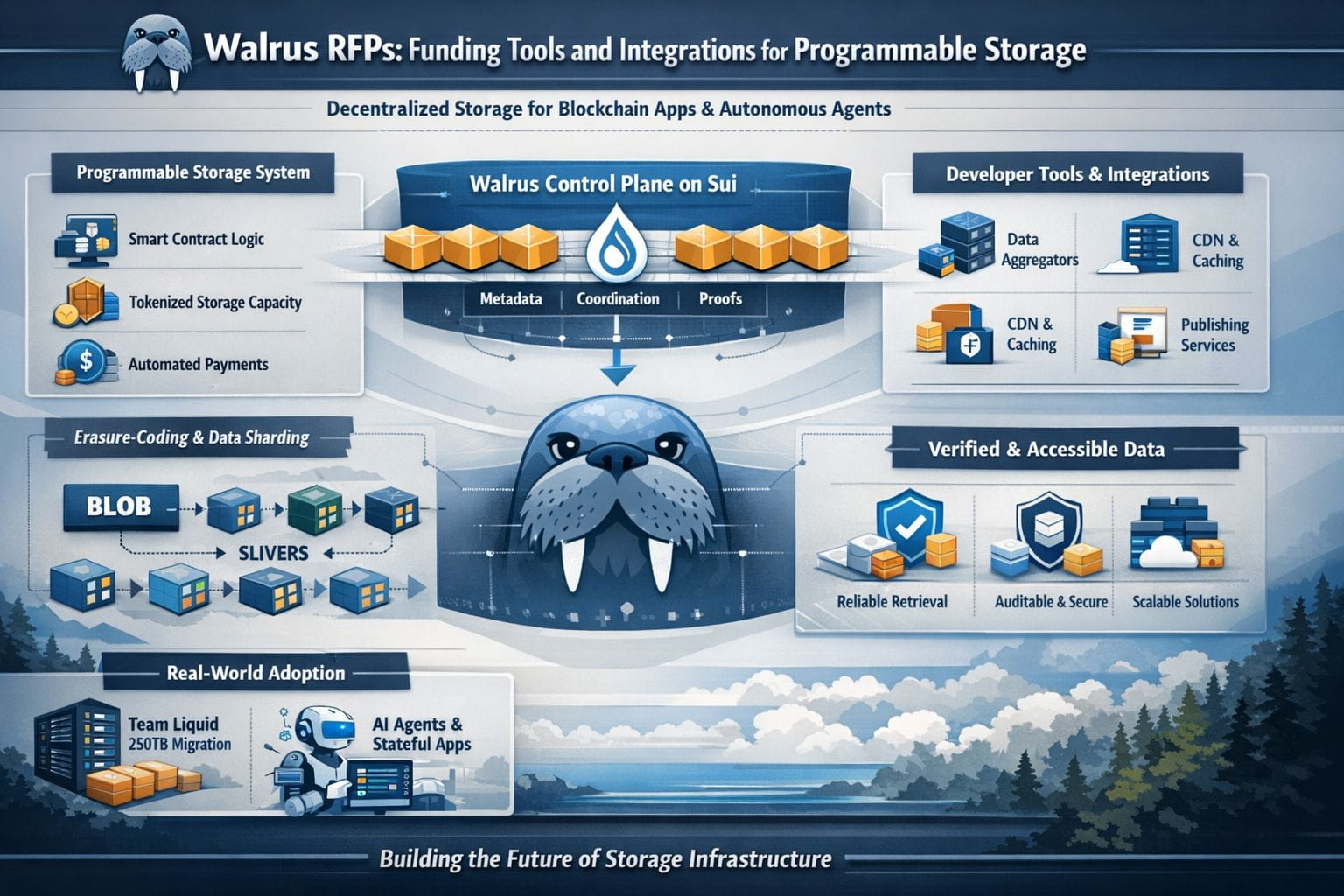

I tend to treat RFPs as a kind of ecosystem self-portrait. In Walrus’ case, the criteria are straightforward in a way I respect: technical strength and execution, realistic milestones, product alignment without losing creativity, and signals that a team will stick around long enough for what they build to matter. That focus makes sense when you look at what Walrus is trying to do under the hood. The basic promise is that large “blob” data can be split into smaller pieces, distributed across many storage nodes, and later reconstructed even if a meaningful chunk of the network is missing or unreliable. Mysten Labs has described Walrus as using erasure-coding techniques to encode blobs into “slivers,” aiming for robustness with a replication factor closer to cloud storage than to full onchain replication.

The part that turns this from “decentralized Dropbox” into “programmable storage” is the control plane. Walrus uses Sui for coordination—tracking metadata, managing payments, and anchoring proofs—so storage actions can be connected to smart-contract logic instead of living off to the side. Walrus also frames storage capacity as something that can be tokenized and represented as an object on Sui, which is a subtle but important shift: storage becomes ownable and transferable in a way that software can reason about.

Once you accept that design, the “integrations” part of the title stops being vague and starts becoming urgent. Walrus documentation describes optional actors—aggregators that reconstruct blobs and serve them over familiar web protocols, caches that reduce latency and can function like CDNs, and publishers that handle the mechanics of encoding and distributing data for users who want a smoother interface. If you’ve ever watched a promising system lose momentum because the developer experience was just a bit too sharp-edged, you can almost feel why an RFP program would aim directly at these pieces.

And the timing really does feel current. The last year has made “stateful” software more visible to normal people, not just engineers. AI agents don’t just generate text; they need memory, reliable datasets, and a way to prove that what they used hasn’t been quietly altered. Walrus has been leaning into that narrative, arguing that agents need data that’s always available and verifiable, not merely “pretty reliable most of the time.” The idea isn’t theoretical either: you can point to concrete momentum like Team Liquid migrating a 250TB content archive to Walrus, which is exactly the kind of workload that forces a protocol to prove it can handle scale without falling apart.

What I like about the RFP framing is that it doesn’t pretend funding alone creates adoption. It’s more like a coordination tool for finishing the job: SDKs that feel familiar, monitoring that tells you what’s happening when something goes wrong, integrations that let you serve data fast without abandoning verifiability, and connectors that make Walrus usable beyond one narrow lane. Walrus itself explicitly talks about delivery through CDNs or read caches, and about integrations beyond a single chain, which is a practical acknowledgment that “decentralized” still has to meet users where they are.

If this works, the win won’t be a dramatic headline. It’ll be quieter. Storage will become something builders reach for without turning it into an identity debate, because the tooling and integrations make it feel dependable. And in infrastructure, that kind of quiet is usually the point.