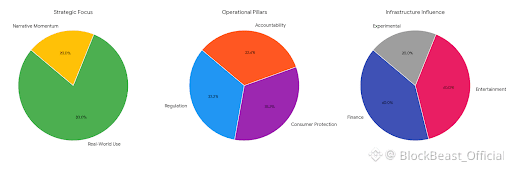

Vanar positions itself as a layer-1 blockchain built with an awareness of how real systems operate once they leave experimental environments. Rather than framing adoption as a purely technical challenge, the project appears to start from the assumption that regulation, consumer protection, and operational accountability are unavoidable constraints. This mindset is common in traditional financial and entertainment infrastructure, where scale quickly attracts scrutiny and informal practices do not survive.

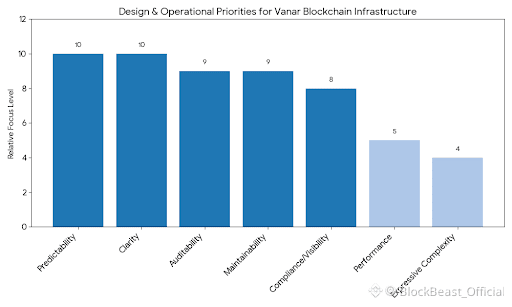

The focus on gaming, entertainment, and brand ecosystems reflects an understanding that these sectors already function under complex legal and commercial frameworks. Payments, digital ownership, user data, and licensing obligations are not theoretical concerns in these industries; they are operational realities. Designing blockchain infrastructure for such environments requires predictability and clarity more than maximal performance or expressive complexity. Vanar’s design choices suggest a preference for systems that can be explained, audited, and maintained over long periods, even if that limits short-term flexibility.

Privacy within this framework is treated less as an absolute guarantee and more as a managed capability. In regulated environments, selective disclosure is often more valuable than full anonymity. The ability to demonstrate compliance, resolve disputes, or provide transaction visibility to authorized parties is a requirement, not a compromise. Systems that acknowledge this reality are better aligned with how institutions and large consumer platforms actually operate.

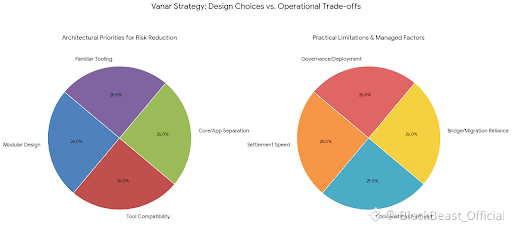

Architecturally, conservative choices such as modular design and compatibility with established development tools indicate an intent to reduce long-term risk. Separation between core protocol functions and application logic makes upgrades more manageable and failures more contained. Familiar tooling lowers the barrier for professional teams who must prioritize maintainability and security over experimentation.

These decisions come with practical limitations. Settlement speed, coordination overhead for upgrades, and reliance on bridges or migration mechanisms introduce trade-offs that affect governance and deployment. In production environments, these are not abstract weaknesses but factors that must be actively managed. Vanar’s approach appears to accept these constraints rather than obscure them.

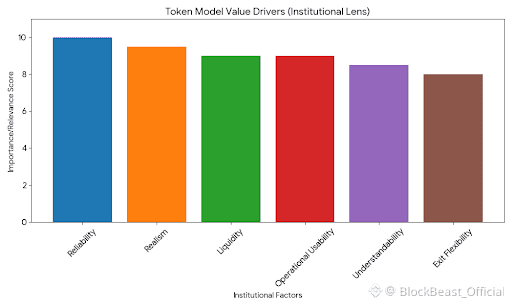

The token model, viewed through an institutional lens, is most relevant in terms of liquidity, operational usability, and exit flexibility. For serious participants, the value of a token lies less in speculative upside and more in whether it integrates cleanly into existing financial and compliance processes.

Overall, Vanar can be understood as infrastructure designed to function under sustained scrutiny rather than momentary attention. Its success is unlikely to be measured by visibility or narratives, but by whether it remains operational, understandable, and reliable as external expectations increase. In regulated and consumer-facing environments, quiet durability is often the clearest indicator that a system was built with realism rather than ambition as its primary guide.