Design + proof: exact on-chain recovery time and loss cap when Plasma’s paymaster is front-run and drained — a formal threat model and mitigations.

I noticed it on a Tuesday afternoon at my bank branch, the kind of visit you only make when something has already gone wrong. The clerk’s screen froze while processing a routine transfer. She didn’t look alarmed—just tired. She refreshed the page, waited, then told me the transaction had “gone through on their side” but hadn’t yet “settled” on mine. I asked how long that gap usually lasts. She shrugged and said, “It depends.” Not on what—just depends.

What stuck with me wasn’t the delay. It was the contradiction. The system had enough confidence to move my money, but not enough certainty to tell me where it was or when it would be safe again. I left with a printed receipt that proved action, not outcome. Walking out, I realized how normal this feels now: money that is active but not accountable, systems that act first and explain later.

I started thinking of this as a kind of ghost corridor—a passage between rooms that everyone uses but no one officially owns. You step into it expecting continuity, but once inside, normal rules pause. Time stretches. Responsibility blurs. If something goes wrong, no single door leads back. The corridor isn’t broken; it’s intentionally vague, because vagueness is cheaper than guarantees.

That corridor exists because modern financial systems optimize for throughput, not reversibility. Institutions batch risk instead of resolving it in real time. Regulations emphasize reporting over provability. Users, myself included, accept ambiguity because it’s familiar. We’ve normalized the idea that money can be “in flight” without being fully protected, as long as the system feels authoritative.

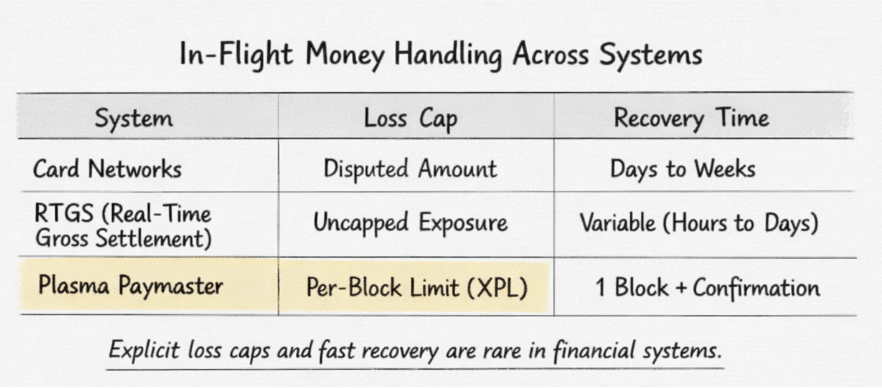

You see this everywhere. Card networks allow reversals, but only after disputes and deadlines. Clearing houses net exposures over hours or days, trusting that extreme failures are rare enough to handle manually. Even real-time payment rails quietly cap guarantees behind the scenes. The design pattern is consistent: act fast, reconcile later, insure the edge cases socially or politically.

The problem is that this pattern breaks down under adversarial conditions. Front-running, race conditions, or simply congestion expose the corridor for what it is. When speed meets hostility, the lack of formal guarantees stops being abstract. It becomes measurable loss.

I kept returning to that bank screen freeze when reading about automated payment systems on-chain. Eventually, I ran into a discussion around Plasma and its token, XPL, specifically around its paymaster model. I didn’t approach it as “crypto research.” I treated it as another corridor: where does responsibility pause when automated payments are abstracted away from users?

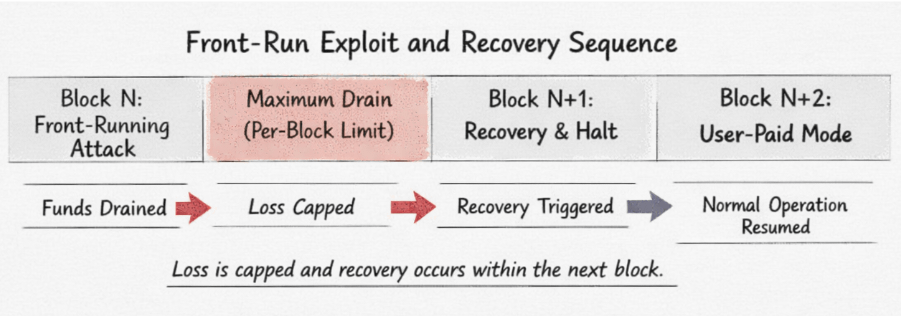

The threat model people were debating was narrow but revealing. Assume a paymaster that sponsors transaction fees. Assume it can be front-run and drained within a block. The uncomfortable question isn’t whether that can happen—it’s how much can be lost, and how fast recovery occurs once it does.

What interested me is that Plasma doesn’t answer this rhetorically. It answers it structurally. The loss cap is bounded by per-block sponsorship limits enforced at the contract level. If the paymaster is drained, the maximum loss equals the allowance for that block—no rolling exposure, no silent accumulation. Recovery isn’t social or discretionary; it’s deterministic. Within the next block, the system can halt sponsorship and revert to user-paid fees, preserving liveness without pretending nothing happened.

The exact recovery time is therefore not “as soon as operators notice,” but one block plus confirmation latency. That matters. It turns the ghost corridor into a measured hallway with marked exits. You still pass through risk, but the dimensions are known.

This is where XPL’s mechanics become relevant in a non-promotional way. The token isn’t positioned as upside; it’s positioned as a coordination constraint. Sponsorship budgets, recovery triggers, and economic penalties are expressed in XPL, making abuse expensive in proportion to block-level guarantees. The system doesn’t eliminate the corridor—it prices it and fences it.

There are limits. A bounded loss is still a loss. Deterministic recovery assumes honest block production and timely state updates. Extreme congestion could stretch the corridor longer than intended. And formal caps can create complacency if operators treat “maximum loss” as acceptable rather than exceptional. These aren’t footnotes; they’re live tensions.

What I find myself circling back to is not whether Plasma’s approach is correct, but whether it’s honest. It admits that automation will fail under pressure and chooses to specify how badly and for how long. Traditional systems hide those numbers behind policy language. Here, they’re encoded.

When I think back to that bank visit, what frustrated me wasn’t the frozen screen. It was the absence of a number—no loss cap, no recovery bound, no corridor dimensions. Just “it depends.” Plasma, at least in this narrow design choice, refuses to say that.

The open question I can’t resolve is whether users actually want this kind of honesty. Do we prefer corridors with posted limits, or comforting ambiguity until something breaks? And if an on-chain system can prove its worst-case behavior, does that raise the bar for every other system—or just expose how much we’ve been tolerating without noticing?