Formal specification of deterministic finality rules that keep Plasma double-spend-safe under deepest plausible Bitcoin reorganizations.

Last month, I stood inside a nationalized bank branch in Mysore staring at a small printed notice taped to the counter: “Transactions are subject to clearing and reversal under exceptional settlement conditions.” I had just transferred funds to pay a university fee. The app showed “Success.” The SMS said “Debited.” But the teller quietly told me, “Sir, wait for clearing confirmation.”

I remember watching the spinning progress wheel on my phone, then glancing at the ceiling fan above the counter. The money had left my account. The university portal showed nothing. The bank insisted it was done—but not done. It was the first time I consciously noticed how many systems operate in this strange middle state: visibly complete, technically reversible.

That contradiction stayed with me longer than it should have. What does “final” actually mean in a system that admits the possibility of reversal?

That day forced me to confront something subtle: modern settlement systems do not run on absolute certainty. They run on probabilistic comfort.

I started thinking of settlement as walking across wet cement.

When you step forward, your footprint looks permanent. But for a short time, it isn’t. A strong disturbance can still distort it. After a while, the cement hardens—and the footprint becomes history.

The problem is that most systems don’t clearly specify when the cement hardens. They give us heuristics. Six confirmations. Three business days. T+2 settlement. “Subject to clearing.”

The metaphor works because it strips away jargon. Every settlement layer—banking, securities clearinghouses, card networks—operates on some version of wet cement. There’s always a window where what appears settled can be undone by a sufficiently powerful event.

In financial markets, we hide this behind terms like counterparty risk and systemic liquidity events. In distributed systems, we call it reorganization depth or chain rollback.

But the core question remains brutally simple:

At what point does a footprint stop being wet?

The deeper I looked, the clearer it became that finality is not a binary property. It’s a negotiated truce between probability and economic cost.

Take traditional securities settlement. Even after trade execution, clearinghouses maintain margin buffers precisely because settlement can fail. Failures-to-deliver happen. Liquidity crunches happen. The system absorbs shock using layered capital commitments.

In proof-of-work systems like Bitcoin, the problem is structurally different but conceptually similar. Blocks can reorganize if a longer chain appears. The probability decreases with depth, but never truly reaches zero.

Under ordinary conditions, six confirmations are treated as economically irreversible. Under extraordinary conditions—extreme hashpower shifts, coordinated attacks, or mining centralization shocks—the depth required to consider a transaction “final” increases.

The market pretends this is simple. It isn’t.

What’s uncomfortable is that many systems building on top of Bitcoin implicitly rely on the assumption that deep reorganizations are implausible enough to ignore in practice. But “implausible” is not a formal specification. It’s a comfort assumption.

Any system anchored to Bitcoin inherits its wet cement problem. If the base layer can reorganize, anything built on top must define its own hardness threshold.

Without formal specification, we’re just hoping the cement dries fast enough.

This is where deterministic finality rules become non-optional.

If Bitcoin can reorganize up to depth d, then any dependent system must formally specify:

The maximum tolerated reorganization depth.

The deterministic state transition rules when that threshold is exceeded.

The economic constraints that make violating those rules irrational.

Finality must be defined algorithmically—not culturally.

In the architecture of XPL, the interesting element is not the promise of security but the attempt to encode deterministic responses to the deepest plausible Bitcoin reorganizations.

That phrase—deepest plausible—is where tension lives.

What counts as plausible? Ten blocks? Fifty? One hundred during catastrophic hashpower shifts?

A rigorous specification cannot rely on community consensus. It must encode:

Checkpoint anchoring intervals to Bitcoin.

Explicit dispute windows.

Deterministic exit priority queues.

State root commitments.

Bonded fraud proofs backed by XPL collateral.

If Bitcoin reorganizes deeper than a Plasma checkpoint anchoring event, the system must deterministically decide:

Does the checkpoint remain canonical? Are exits automatically paused? Are bonds slashed? Is state rolled back to a prior root?

These decisions cannot be discretionary. They must be predefined.

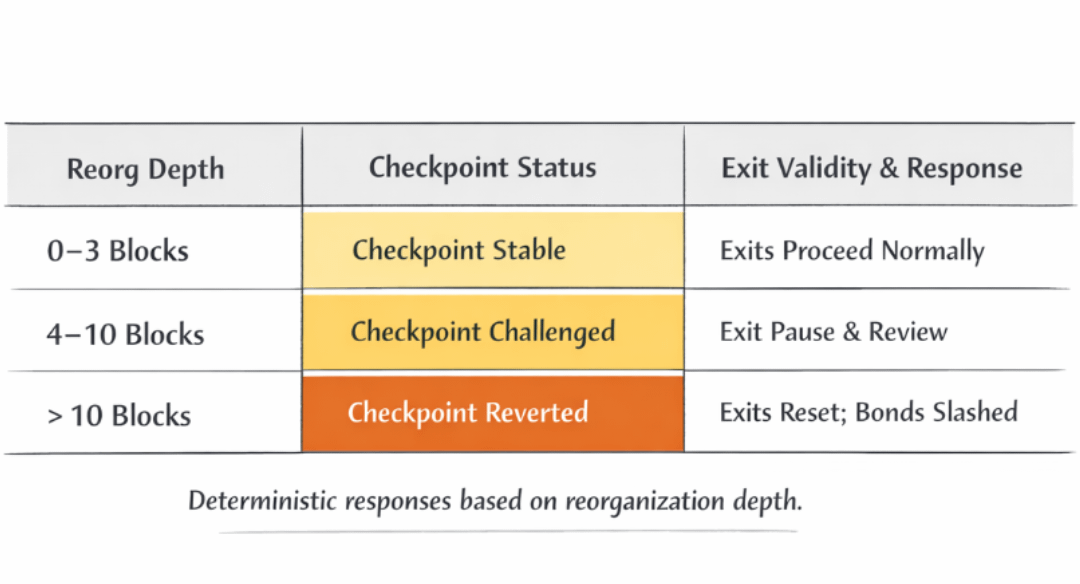

One useful analytical framework would be a structured table mapping reorganization depth ranges to deterministic system responses. For example:

Reorg Depth: 0–3 blocks

Impact: Checkpoint unaffected

Exit Status: Normal

Bond Adjustment: None

Dispute Window: Standard

Reorg Depth: 4–10 blocks

Impact: Conditional checkpoint review

Exit Status: Temporary delay

Bond Adjustment: Multiplier increase

Dispute Window: Extended

Reorg Depth: >10 blocks

Impact: Checkpoint invalidation trigger

Exit Status: Automatic pause

Bond Adjustment: Slashing activation

Dispute Window: Recalibrated

Such a framework demonstrates that for each plausible reorganization range, there is a mechanical response—no ambiguity, no governance vote, no social coordination required.

Double-spend safety in this context is not just about preventing malicious operators. It is about ensuring that even if Bitcoin reorganizes deeply, users cannot exit twice against conflicting states.

This requires deterministic exit ordering, strict priority queues, time-locked challenge windows, and bonded fraud proofs denominated in XPL.

The token mechanics matter here.

If exit challenges require XPL bonding, then economic security depends on:

Market value stability of XPL.

Liquidity depth to support bonding.

Enforceable slashing conditions.

Incentive alignment between watchers and challengers.

If the bond required to challenge a fraudulent exit becomes economically insignificant relative to the potential gain from a double-spend, deterministic rules exist only on paper.

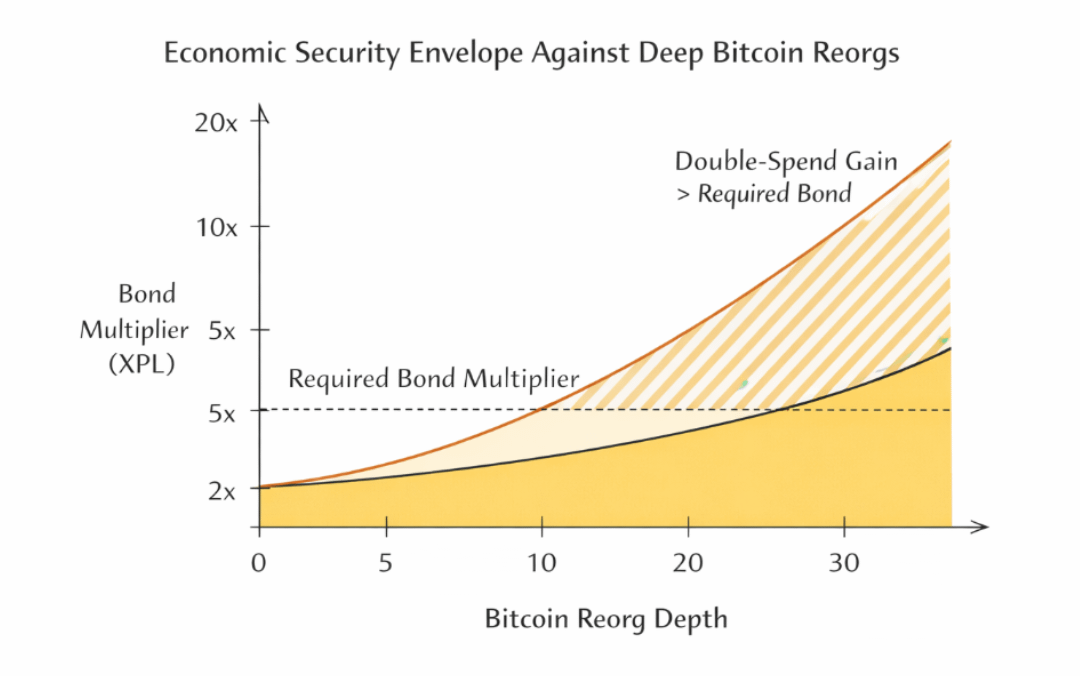

A second analytical visual could model an economic security envelope.

On the horizontal axis: Bitcoin reorganization depth.

On the vertical axis: Required XPL bond multiplier.

Overlay: Estimated cost of executing a double-spend attempt.

The safe region exists where the cost of attack exceeds the potential reward. As reorganization depth increases, required bond multipliers rise accordingly.

This demonstrates that deterministic finality is not only about block depth. It is about aligning economic friction with probabilistic rollback risk.

Here lies the contradiction.

If we assume deep Bitcoin reorganizations are improbable, we design loosely and optimize for speed. If we assume they are plausible, we must over-collateralize, extend exit windows, and introduce friction.

There is no configuration that removes this trade-off.

XPL’s deterministic finality rules attempt to remove subjective trust by predefining responses to modeled extremes. But modeling extremes always involves judgment.

When I stood in that bank branch watching a “successful” transaction remain unsettled, I realized something uncomfortable. Every system eventually chooses a depth at which it stops worrying.

The cement hardens not because reversal becomes impossible—but because the cost of worrying further becomes irrational.

When we define deterministic finality rules under the deepest plausible Bitcoin reorganizations, are we encoding mathematical inevitability—or translating institutional comfort into code?

And if Bitcoin ever reorganizes deeper than our model anticipated, will formal specification protect double-spend safety—or simply record the exact moment the footprint smudged?