Incremental ZK-checkpointing for Plasma: can it deliver atomic merchant settlement with sub-second guarantees and provable data-availability bounds?

Last month I stood at a pharmacy counter in Mysore, holding a strip of antibiotics and watching a progress bar spin on the payment terminal. The pharmacist had already printed the receipt. The SMS from my bank had already arrived. But the machine still said: Processing… Do not remove card.

I remember looking at three separate confirmations of the same payment — printed slip, SMS alert, and app notification — none of which actually meant the transaction was final. The pharmacist told me, casually, that sometimes payments “reverse later” and they have to call customers back.

That small sentence stuck with me.

The system looked complete. It behaved complete. But underneath, it was provisional. A performance of certainty layered over deferred settlement.

I realized what bothered me wasn’t delay. It was the illusion of atomicity — the appearance that something happened all at once when in reality it was staged across invisible checkpoints.

That’s when I started thinking about what I now call “Receipt Theater.”

Receipt Theater is when a system performs finality before it actually achieves it. The receipt becomes a prop. The SMS becomes a costume. Everyone behaves as though the state is settled, but the underlying ledger still reserves the right to rewrite itself.

Banks do it. Card networks do it. Even clearinghouses operate this way. They optimize for speed of perception, not speed of truth.

And this is not accidental. It’s structural.

Large financial systems evolved under the assumption that reconciliation happens in layers. Authorization is immediate; settlement is deferred; dispute resolution floats somewhere in between. Regulations enforce clawback windows. Fraud detection requires reversibility. Liquidity constraints force batching.

True atomic settlement — where transaction, validation, and finality collapse into one irreversible moment — is rare because it’s operationally expensive. Systems hedge. They checkpoint. They reconcile later.

This layered architecture works at scale, but it creates a paradox: the faster we make front-end confirmation, the more invisible risk we push into back-end coordination.

That paradox isn’t limited to banks. Stock exchanges operate with T+1 or T+2 settlement cycles. Payment gateways authorize in milliseconds but clear in batches. Even digital wallets rely on pre-funded balances to simulate atomicity.

We have built a civilization on optimistic confirmation.

And optimism eventually collides with reorganization.

When a base system reorganizes — whether due to technical failure, liquidity shock, or policy override — everything built optimistically above it inherits that instability. The user sees a confirmed state; the system sees a pending state.

That tension is exactly where incremental zero-knowledge checkpointing for Plasma becomes interesting.

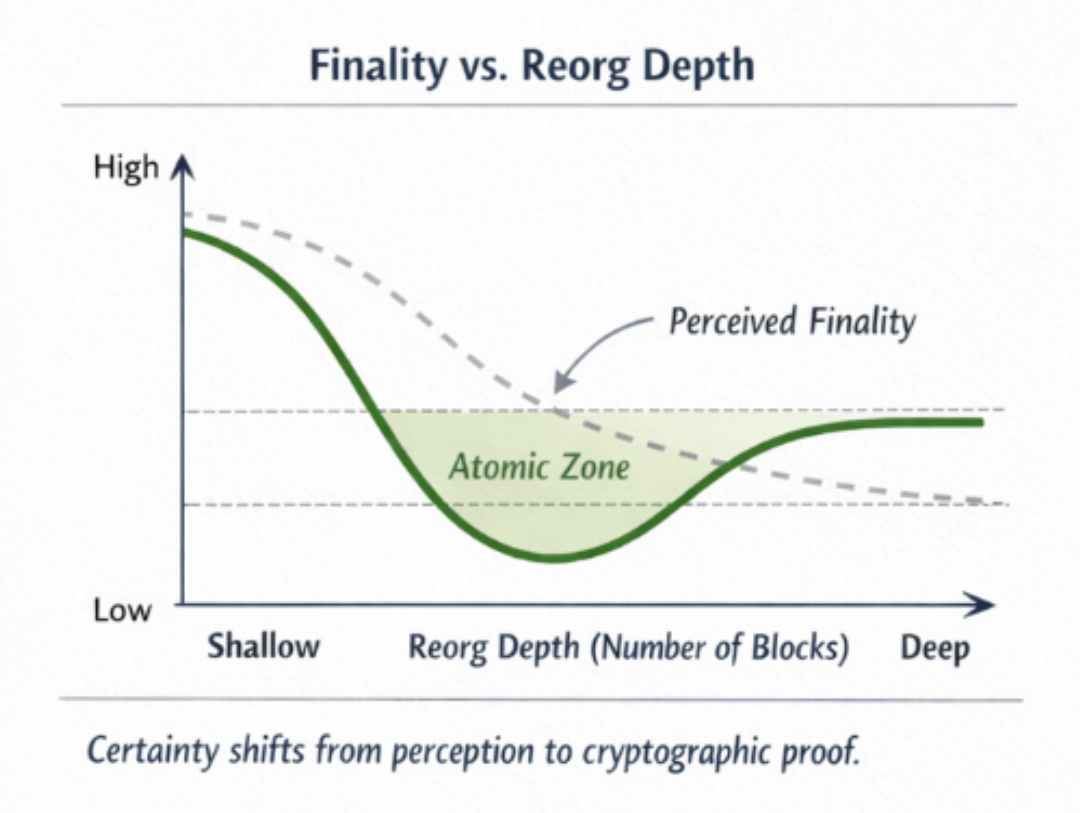

Plasma architectures historically relied on periodic commitments to a base chain, with fraud proofs enabling dispute resolution. The problem is timing. If merchant settlement depends on deep confirmation windows to resist worst-case reorganizations, speed collapses. If it depends on shallow confirmations, risk leaks.

Incremental ZK-checkpointing proposes something different: instead of large periodic commitments, it introduces frequent cryptographic state attestations that compress transactional history into succinct validity proofs. Each checkpoint becomes a provable boundary of correctness.

But here’s the core tension: can these checkpoints provide atomic merchant settlement with sub-second guarantees, while also maintaining provable data-availability bounds under deepest plausible base-layer reorganizations?

Sub-second guarantees are not just about latency. They’re about economic irreversibility. A merchant doesn’t care if a proof exists; they care whether inventory can leave the store without clawback risk.

To think through this, I started modeling the system as a “Time Compression Ladder.”

At the bottom of the ladder is raw transaction propagation. Above it is local validation. Above that is ZK compression into checkpoints. Above that is anchoring to the base layer. Each rung compresses uncertainty, but none eliminates it entirely.

A useful visual here would be a layered timeline diagram showing:

Row 1: User transaction timestamp (t0).

Row 2: ZK checkpoint inclusion (t0 + <1s).

Row 3: Base layer anchor inclusion (t0 + block interval).

Row 4: Base layer deep finality window (t0 + N blocks).

The diagram would demonstrate where economic finality can reasonably be claimed and where probabilistic exposure remains. It would visually separate perceived atomicity from cryptographic atomicity.

Incremental ZK-checkpointing reduces the surface area of fraud proofs by continuously compressing state transitions. Instead of waiting for long dispute windows, the system mathematically attests to validity at each micro-interval. That shifts the burden from reactive fraud detection to proactive validity construction.

But the Achilles’ heel is data availability.

Validity proofs guarantee correctness of state transitions — not necessarily availability of underlying transaction data. If data disappears, users cannot reconstruct state even if a proof says it’s valid. In worst-case base-layer reorganizations, withheld data could create exit asymmetries.

So the question becomes: can incremental checkpoints be paired with provable data-availability sampling or enforced publication guarantees strong enough to bound loss exposure?

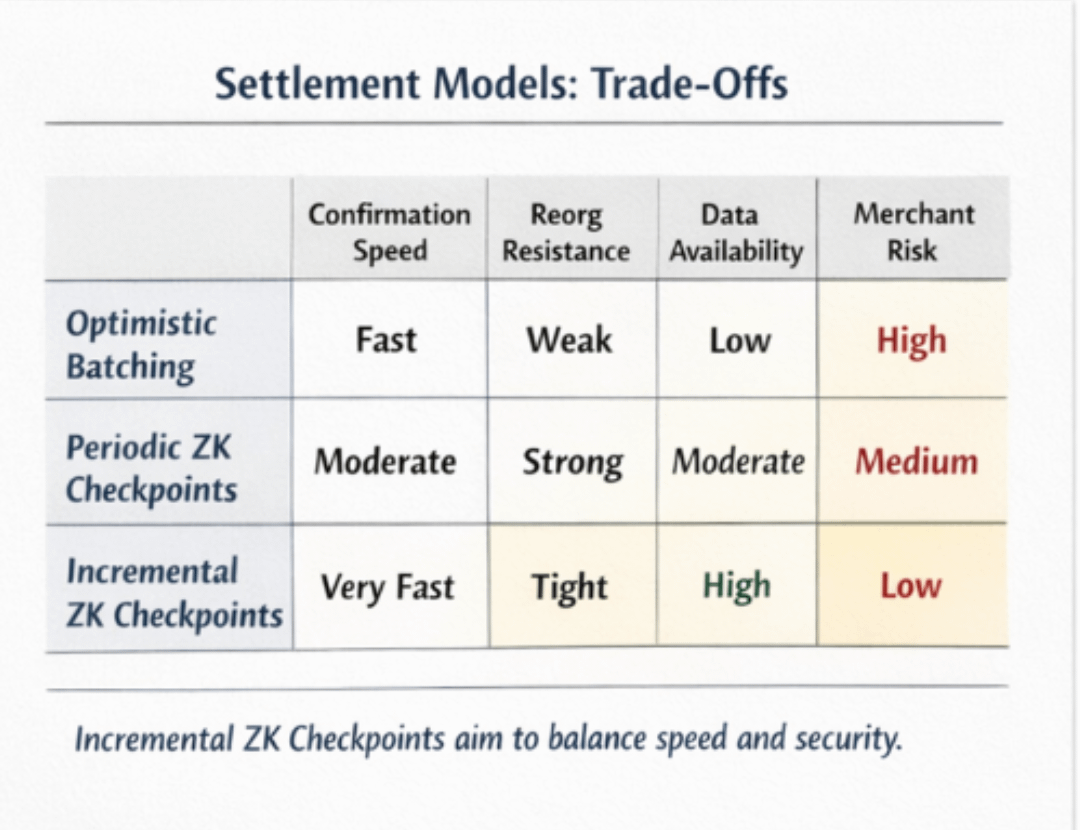

A second visual would help here: a table comparing three settlement models.

Columns:

Confirmation Speed

Reorg Resistance Depth

Data Availability Guarantee

Merchant Clawback Risk

Rows:

1. Optimistic batching model

2. Periodic ZK checkpoint model

3. Incremental ZK checkpoint model

This table would show how incremental checkpoints potentially improve confirmation speed while tightening reorg exposure — but only if data availability assumptions hold.

Now, bringing this into XPL’s architecture.

XPL operates as a Plasma-style system anchored to Bitcoin, integrating zero-knowledge validity proofs into its checkpointing design. The token itself plays a structural role: it is not merely a transactional medium but part of the incentive and fee mechanism that funds proof generation, checkpoint posting, and dispute resolution bandwidth.

Incremental ZK-checkpointing in XPL attempts to collapse the gap between user confirmation and cryptographic attestation. Instead of large periodic state commitments, checkpoints can be posted more granularly, each carrying succinct validity proofs. This reduces the economic value-at-risk per interval.

However, anchoring to Bitcoin introduces deterministic but non-instant finality characteristics. Bitcoin reorganizations, while rare at depth, are not impossible. The architecture must therefore model “deepest plausible reorg” scenarios and define deterministic rules for when merchant settlement becomes economically atomic.

If XPL claims sub-second merchant guarantees, those guarantees cannot depend on Bitcoin’s deep confirmation window. They must depend on the internal validity checkpoint plus a bounded reorg assumption.

That bounded assumption is where the design tension lives.

Too conservative, and settlement latency approaches base-layer speed. Too aggressive, and merchants accept probabilistic exposure.

Token mechanics further complicate this. If XPL token value underwrites checkpoint costs and validator incentives, volatility could affect the economics of proof frequency. High gas or fee environments may discourage granular checkpoints, expanding risk intervals. Conversely, subsidized checkpointing increases operational cost.

There is also the political layer. Data availability schemes often assume honest majority or economic penalties. But penalties only work if slashing exceeds potential extraction value. In volatile markets, extraction incentives can spike unpredictably.

So I find myself circling back to that pharmacy receipt.

If incremental ZK-checkpointing works as intended, it could reduce Receipt Theater. The system would no longer rely purely on optimistic confirmation. Each micro-interval would compress uncertainty through validity proofs. Merchant settlement could approach true atomicity — not by pretending, but by narrowing the gap between perception and proof.

But atomicity is not a binary state. It is a gradient defined by bounded risk.

XPL’s approach suggests that by tightening checkpoint intervals and pairing them with cryptographic validity, we can shrink that gradient to near-zero within sub-second windows — provided data remains available and base-layer reorgs remain within modeled bounds.

And yet, “modeled bounds” is doing a lot of work in that sentence.

Bitcoin’s deepest plausible reorganizations are low probability but non-zero. Data availability assumptions depend on network honesty and incentive calibration. Merchant guarantees depend on economic rationality under stress.

So I keep wondering: if atomic settlement depends on bounded assumptions rather than absolute guarantees, are we eliminating Receipt Theater — or just performing it at a more mathematically sophisticated level?

If a merchant ships goods at t0 + 800 milliseconds based on an incremental ZK checkpoint, and a once-in-a-decade deep reorganization invalidates the anchor hours later, was that settlement truly atomic — or merely compressed optimism?

And if the answer depends on probability thresholds rather than impossibility proofs, where exactly does certainty begin?