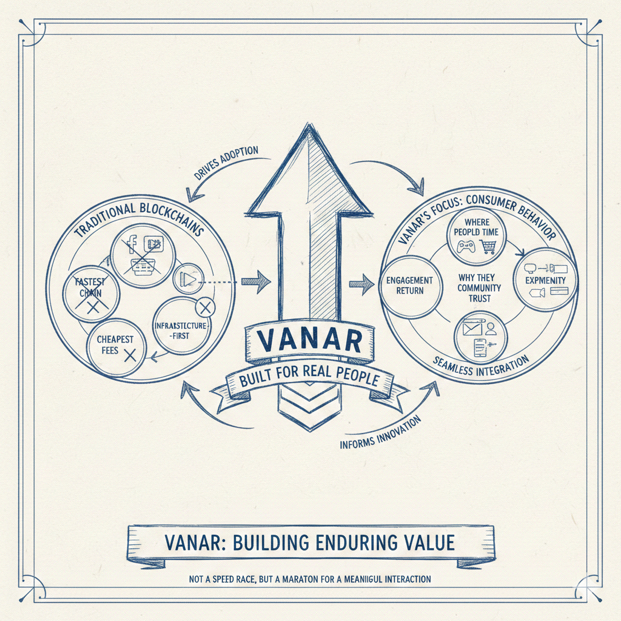

Vanar, I don’t see a project trying to win a race for “fastest chain” or “cheapest fees,” because those contests never stay won for long, and anyone with enough resources can copy the surface-level features that dominate crypto conversations. What stands out instead is how deliberately Vanar seems to be built around consumer behavior, meaning it pays more attention to where real people already spend time and why they return, rather than assuming they’ll show up just because the infrastructure is impressive.

A useful way to understand Vanar is to stop thinking in terms of features and start thinking in terms of moats, because a moat is the kind of advantage that keeps working even when market narratives flip and attention moves on. In Web3, moats rarely come from technology alone, since performance improvements become common knowledge quickly and competing networks can replicate technical patterns with surprising speed. The moats that last tend to come from distribution, product loops, and the ability to create environments where people participate naturally without feeling like they are stepping into something foreign.

Vanar’s strongest distribution logic is rooted in entertainment, and this matters because entertainment is one of the few categories where onboarding can happen almost invisibly. People do not wake up wanting to “use blockchain,” but they do wake up wanting to play, explore, collect, socialize, and feel part of a culture, and those motivations are far more powerful than any argument about decentralization or throughput. When the entry point is entertainment, the first experience can feel familiar and rewarding rather than risky and technical, and that shift changes everything because users are more willing to learn small steps when the experience itself is already giving them value.

That consumer-first direction becomes even more meaningful when it is paired with a product stack rather than a chain-only approach, because ecosystems grow faster when there are multiple real surfaces where usage can happen. Many networks build the base layer and then wait for developers to create a reason for normal people to care, which often turns into a slow and uncertain process, since it depends on external teams to both build great experiences and solve onboarding problems at the same time. Vanar’s approach feels more like building the infrastructure while also cultivating the kinds of consumer-facing environments that create repeat behavior, and repeat behavior is the difference between a network that looks active during marketing cycles and one that feels alive even when nobody is pushing a campaign.

The flywheel that emerges from this kind of setup is the part that competitors struggle to replicate, because the loop is not just technical, it is behavioral and commercial at the same time. When products attract users, those users create consistent activity, and that activity makes the ecosystem more attractive to creators, studios, and brands that want attention with less friction, and those partners bring their own audiences who add even more activity, which strengthens the overall ecosystem without requiring the same level of constant outreach. This is how structural demand forms, because the network’s value starts coming from usage that is connected to experiences people actually want, rather than from speculation that depends on external excitement.

If that loop keeps working, the token becomes more than a symbol, because it starts behaving like a utility layer that benefits from growth in the underlying products. The healthiest token stories are the ones where people interact with the token because it is naturally embedded in what they are doing inside the ecosystem, not because they are being told to hold it for narrative reasons, and the more the network can tie meaningful actions to the token in a way that feels seamless inside products, the more the token’s role shifts from “something you trade” to “something you use because the ecosystem is active.”

There is also an important, often ignored moat in being built for brand-grade expectations, because mainstream partnerships have very different standards than crypto-native communities. Brands care about reliability, predictable costs, clean user experience, and support processes that don’t collapse when a campaign is live, and those requirements are not solved by marketing or by one-time integrations. A chain that wants to work with brands has to behave like dependable infrastructure, and it has to support consumer experiences without forcing people to understand wallets, gas behavior, or complicated onboarding flows, and that kind of operational maturity is hard to fake because it shows up in delivery quality over time.

What keeps Vanar’s story coherent is that it is not trying to be a general-purpose L1 for every possible category, since general-purpose positioning often leads to messy ecosystem choices and scattered roadmaps that serve nobody deeply. Vanar’s emphasis on consumer adoption through entertainment-centric pathways acts like a filter that guides partnerships, product decisions, and ecosystem focus, and that clarity becomes an advantage because it keeps effort concentrated on a few things that compound instead of many things that dilute.

All of this becomes more believable when the risks are acknowledged clearly, because consumer-first strategies only become moats if the products retain users and the onboarding stays simple enough that it does not feel crypto-native. If products fail to create repeat behavior, then the flywheel never reaches the point where it can feed itself, and if onboarding keeps pushing complexity onto users, then the mainstream audience that matters most will quietly leave and never return. The moat can also weaken if competing consumer platforms simply out-distribute, because in entertainment attention is the currency, and the best technology can still lose if it cannot reach people at scale through strong channels and partnerships.