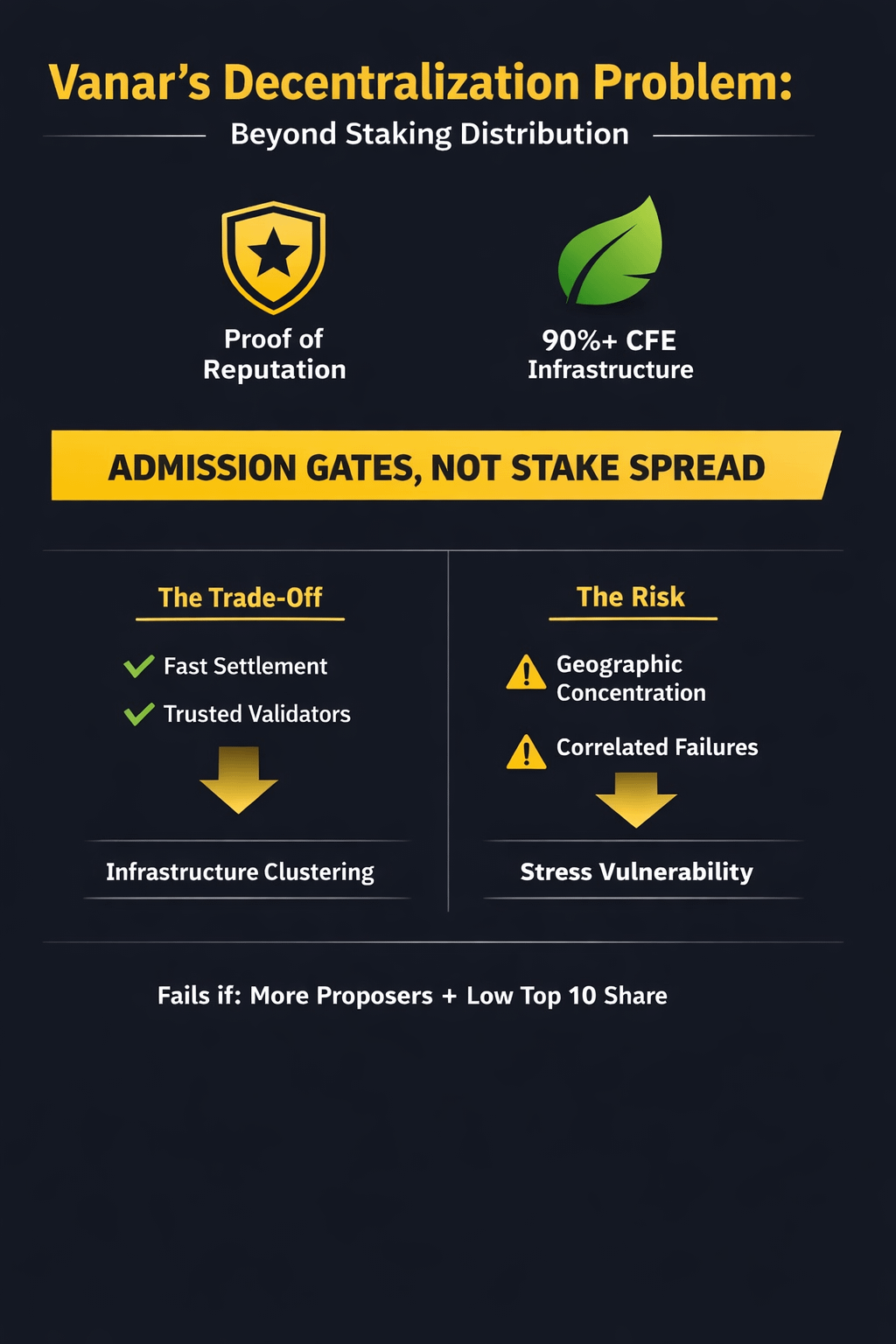

I stopped treating Vanar’s decentralization as a staking-distribution story when I traced how a validator actually gets admitted. Two items dominate the onboarding path: the Vanar Foundation’s Proof of Reputation internal scoring, and the Green Vanar requirement to run validator infrastructure that meets a high CFE% standard that the setup guidance lists as ≥90. Those are admission gates. They shape who can qualify and who can keep qualifying, even if $VANRY stake spreads across more wallets.

That framing changes what I look at. On Vanar, stake concentration can move without changing operational participation, because admission and retention are upstream. Proof of Reputation can filter who enters the active set, and Green Vanar can narrow which operators can run a compliant setup in the first place. Stake can disperse while block production still rotates through a tight set of admitted validators, which is why token distribution is not the main signal I trust for Vanar.

The operational constraint is concrete. A high CFE% requirement is not equally achievable across regions, budgets, and hosting stacks. In practice it pushes operators toward a narrower menu of data centers, cloud vendors, and hardware profiles that can consistently meet the required efficiency profile across time. That is a supply constraint, not a narrative. When validators converge on the same compliant providers and regions, they inherit the same fault domains and the same operational dependencies.

Here is the system-property split that matters to me in Vanar: settlement consistency versus liveness under correlated infrastructure shocks. Admission gates can support consistent operations because the network selects for operators and setups that are easier to keep stable, which can show up as smoother proposer rotation and fewer gaps in production during normal conditions. The trade-off is that liveness becomes more sensitive to shared dependencies. A routing incident, a provider outage, or a policy change at a small set of hosts can hit multiple validators at once. The chain can look fine on a quiet day, then show clustered degradation under stress as missed production and uneven proposer participation.

Once admission is the control-plane, decentralization shows up in proposer rotation and participation, not in staking charts. I watch whether block production rotates across many validators or repeats through a small cohort. I look for long runs where the same operators keep proposing blocks. I also track whether those patterns change over time, because admission that is being broadened should leave a trace in proposer diversity and in how quickly new validators move from present to consistently active.

This is the specific mispricing I see in Vanar. People price decentralization as if more staking automatically maps to more operational participation. On Vanar, Proof of Reputation and Green Vanar can break that mapping. The economic surface can look healthier while the operational surface stays concentrated. If the gates are binding, decentralization improvements become bottlenecked by the operators who can satisfy both the reputational filter and the infrastructure constraint.

None of this makes the design wrong. A chain built for mainstream adoption has incentives to prefer validators that are operationally mature and easier to hold accountable. Proof of Reputation is one way to apply that preference, and Green Vanar is another. The cost is that the validator set can drift toward infrastructure and geography clustering, which is the opposite of what you want when you measure resilience by fault-domain diversity. When that clustering exists, the network can look stable until it hits a correlated infrastructure event that affects the same cohort.

So when I evaluate Vanar, I treat Proof of Reputation and Green Vanar as first-class consensus inputs even if they are not smart contracts I can query. They still determine who can participate in block production, and that shows up directly in proposer distribution you can measure from the chain. If admission constraints are loosening, proposer diversity should rise in a sustained way and concentration should fall as new operators enter and stay active. If the gates are tight, the same cohort should keep carrying block production even as staking looks broader.

To judge Vanar’s decentralization in practice, I prioritize proposer dispersion over staking narratives because it reflects the admission gate in motion, and I use it as a practical read on whether the network is actually reducing correlated infrastructure risk. This thesis fails if the number of distinct block proposers keeps rising over time while the top-10 proposer share stays flat or declines.