Vanar’s developer docs are almost aggressively plain. Chain ID 2040. Public RPC and websocket endpoints. The native token (VANRY). The kind of page a developer skims once, copies from, and closes. If you’re building consumer software, that’s what you want: fewer “learn this new universe” moments, more “plug it in and ship.” Vanar’s own documents lean into that same instinct. The network isn’t presented like a belief system. It’s presented like an appliance.

The funny thing is, Vanar wasn’t always Vanar. The project’s current identity is attached to a fairly clean historical marker: the 2023 token swap and rebrand, where Virtua’s TVK became Vanar’s VANRY at a 1:1 ratio. That’s not just trivia. It tells you this wasn’t a brand-new chain emerging from a vacuum; it was an attempt to redirect an existing project into a new role. The swap was publicly announced and executed as an official migration—one name and ticker stepping aside so another could take the stage.

Rebrands in crypto happen all the time, and most of them are cosmetic. This one felt more structural. Virtua had a recognizable “entertainment/metaverse” identity, the kind that can attract attention but also get boxed in. Vanar’s new posture is more infrastructural: “we’re the rails,” not “we’re the attraction.” That shift changes the type of scrutiny you should apply. If you’re selling infrastructure, you don’t get graded on vibes. You get graded on reliability, integration friction, and whether your public data holds up under a mildly skeptical glance.

That’s where Vanar’s engineering choices become the real story.

Under the hood, Vanar describes itself as EVM-compatible and, more specifically, as a fork of Geth (Go-Ethereum). That’s a telling decision. It’s not romantic. It’s not exotic. It’s pragmatic. If you’re trying to reduce friction for developers, you don’t ask them to rewrite their mental model of smart contracts. You let them bring the same tools, the same contract patterns, the same deployment habits, and you focus your differentiation on the stuff that actually affects user experience: cost, speed, finality, operational control, and the shape of the ecosystem around it.

A lot of projects claim “EVM-compatible.” Fewer make a point of tying themselves directly to Geth lineage. It signals a kind of seriousness: we’re not trying to reinvent execution from scratch; we’re trying to make the overall experience smoother using familiar foundations.

Then you hit the next layer: fees.

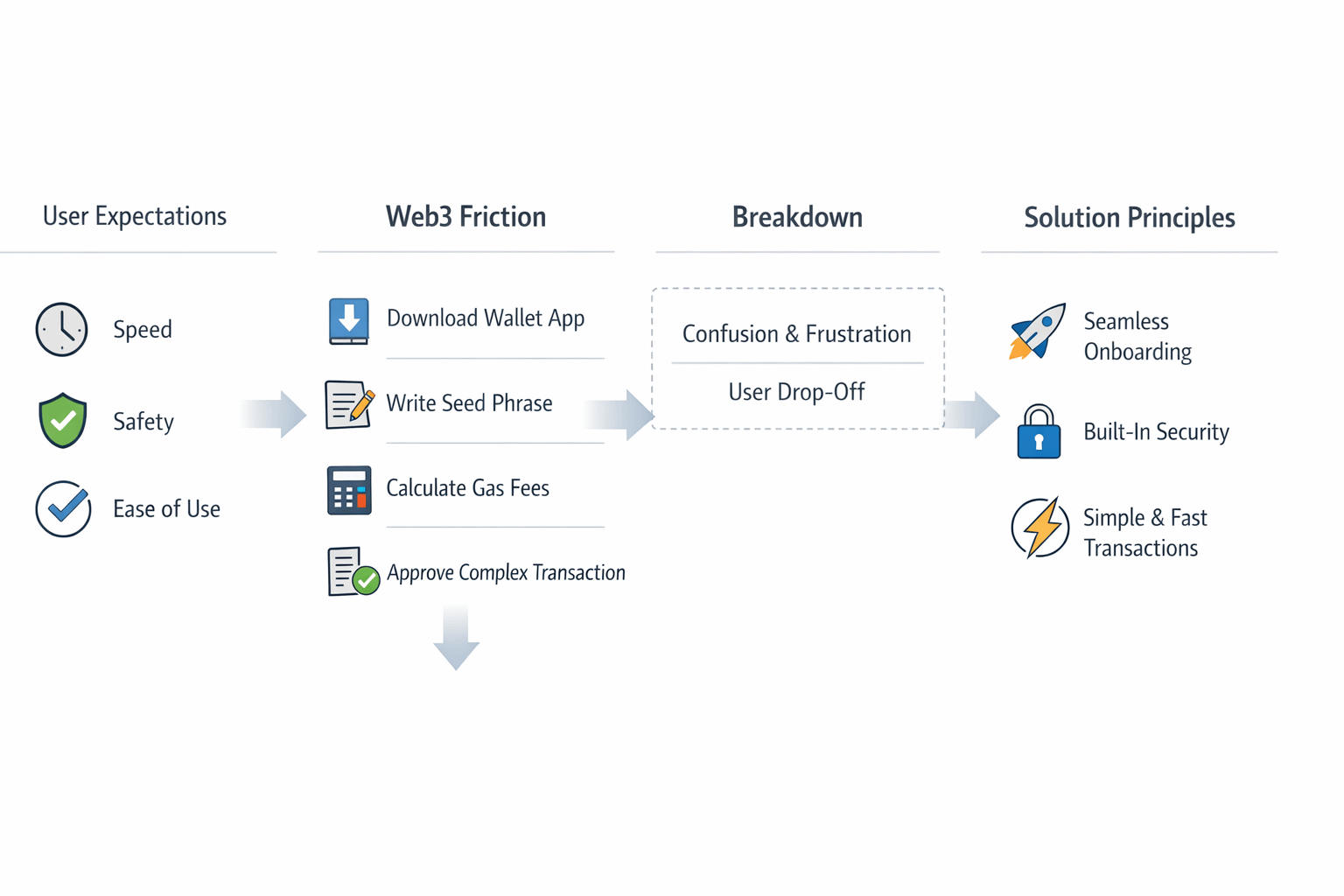

Vanar’s whitepaper includes a fee figure—$0.0005 per transaction—as a target, framed as “fixed transaction costs.” Ignore whether that precise number holds at all times; the intention is what matters. “Low fees” is a vague promise. “Fixed” is a product promise. It’s Vanar saying: we want the cost of an action to feel like a negligible background detail, not a moment where a user stops and does math.

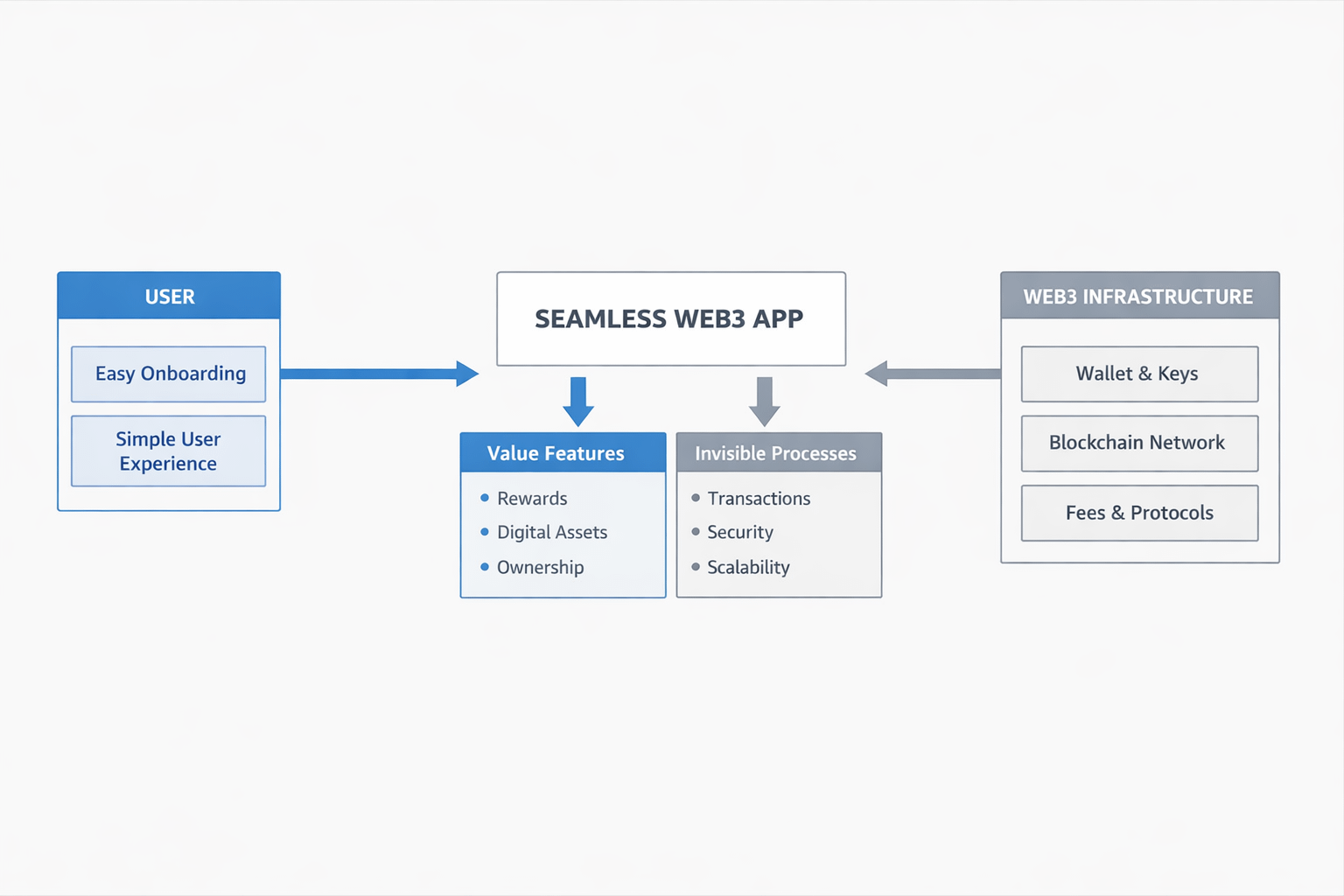

If you’ve ever watched a non-crypto person use a wallet for the first time, you know why this matters. They don’t get stuck on cryptography. They get stuck on uncertainty. They ask, “Why did it cost that?” “Why is it different now?” “Why am I paying at all just to click a button?” A chain that wants mass-market entertainment use has to treat those questions as existential.

So I looked for the obvious next checkpoint: public activity and telemetry.

Vanar’s explorer presents the usual big counters—blocks, transactions, wallet addresses. On paper, it looks like volume. But then the small cracks appear. On a recent pass, the “latest blocks” list showed timestamps like “3y ago,” which doesn’t make sense for a live network. The stats page displayed multiple “Placeholder Counter” entries. These aren’t the sort of issues that prove a chain is broken, but they do something almost as damaging for an infrastructure narrative: they make you hesitate before trusting any headline metric.

When a project positions itself as the kind of chain mainstream partners can build on, clean reporting is not optional. It’s part of the contract. Not because everyone is obsessive, but because every serious integration eventually runs into someone whose job is to ask dull questions—compliance, risk, operations. Those people don’t want stories. They want dashboards that don’t glitch.

This is where Vanar’s “hide the complexity” pitch starts to feel like a tightrope. Because hiding complexity isn’t only about UX; it’s also about giving sophisticated stakeholders clean visibility when they demand it. Ordinary users want invisibility. Professional users want transparency. A project has to serve both at the same time.

And then there’s governance—where Vanar is surprisingly upfront.

Vanar’s docs describe a hybrid consensus setup built primarily on Proof of Authority (PoA), complemented by Proof of Reputation (PoR). It also states that, initially, validators are operated by the Vanar Foundation, with external participants planned later through reputation-based onboarding.

This is the part where the project’s priorities come into focus. PoA is a choice you make when you care about predictable operation. It’s a structure that can be appealing to enterprise partners because it limits unknowns: validator identities, governance control, operational response. In crypto culture, that choice often gets framed as a sin. In practical product terms, it’s a trade. You’re swapping some permissionlessness for a network that can behave like infrastructure brands are willing to touch.

Proof of Reputation is the narrative bridge—an attempt to say: we’re not staying closed forever; we’re designing a filter that’s about credibility rather than just capital. Reputation systems are not inherently bogus. But they have a built-in question that never goes away: who defines “reputation,” and how do you stop the definition from becoming a permanent gatekeeping tool?

This is one of those areas where no amount of documentation settles the debate. The only real evidence will be what happens over time. Does the validator set diversify in a measurable way? Are criteria public and consistent? Can an outsider audit the process without needing to be “in the room”?

Vanar also wraps itself in a broader “AI stack” framing—naming layers, talking about AI workloads, inference, storage, search. That’s where I’d keep my skepticism switched on. Not because “AI” is automatically nonsense, but because crypto has a habit of adopting whatever vocabulary is currently hot and using it to inflate ordinary engineering into a grand narrative.

The fairest way to put it is this: Vanar’s most verifiable parts are its chain fundamentals—EVM/Geth roots, published endpoints, consensus model descriptions, token role, and the existence of a working explorer. The “AI-native” ambition may be real, but from the outside, it needs independent confirmation through usage: third-party apps depending on those components in production, not just Vanar describing them.

The token piece, interestingly, isn’t where Vanar tries to perform. VANRY is treated as a native gas token, with a wrapped form for interoperability. Market data sites list its circulating supply and max supply, the usual financial framing. There’s no need to pretend the token is a magic wand. That restraint fits the project’s larger personality: the token shouldn’t be the entertainment; it should be the meter running quietly in the background.

But even that has practical implications. A chain that aims for tiny, predictable fees has to make the economics work. “Cheap” isn’t free. Validators need incentives. Infrastructure has costs. Either you depend on massive volume, tight governance control, or some other mechanism to keep the system sustainable without making fees unpredictable. Again: not a moral judgment. Just the math that sits behind every “smooth experience” promise.

So what’s the human read on Vanar, after walking through the boring parts and the messier parts?

It feels like a project built by people who want consumer-grade behavior from crypto infrastructure. The choices line up with that: familiar developer environment, emphasis on low and stable transaction costs, governance structure designed for predictability early on. It’s coherent.

At the same time, coherence isn’t the same thing as proof. Vanar’s public telemetry needs to tighten up if it wants outsiders to treat its adoption claims as more than a storyline. The decentralization roadmap needs to become visible in validator composition and governance practice, not just in language. The “AI stack” narrative needs third-party evidence in the wild, not just nice architecture diagrams.

If Vanar succeeds, the win will look almost boring: apps where users never have to learn what VANRY is, never have to understand chain IDs, never have to treat “gas” as a concept. And the people who do care—developers, analysts, partners—will see clean dashboards, stable performance, and a governance model that doesn’t require blind faith.

If it fails, it probably won’t be because the thesis was wrong. It will be because the hard parts of making infrastructure “invisible” are also the hard parts of making it trustworthy: transparency, operational excellence, and the slow grind of proving reliability without asking anyone to clap.