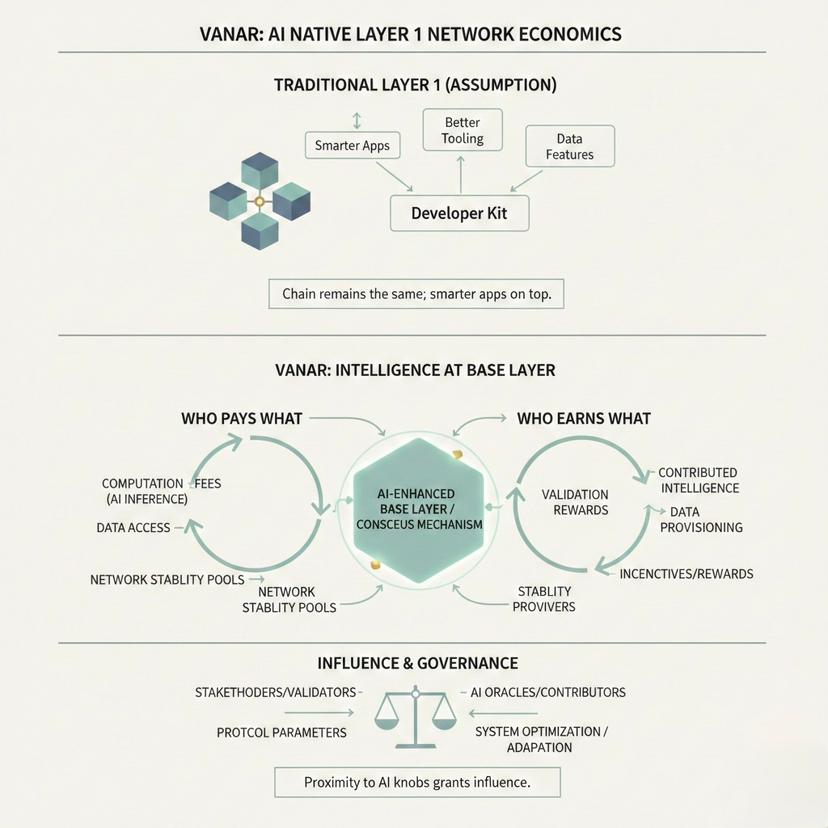

Most people hear AI native Layer 1 and picture a nicer developer kit. Better tooling, a few built in data features, maybe some agent support. The chain itself stays the same, just with smarter apps on top. Vanar makes that assumption hard to hold. When you try to push intelligence closer to the base layer, you end up changing the day to day economics of the network: who pays what, who earns what, and who quietly gains influence just by being closer to the knobs that keep the system stable.

The first place this shows up is fees. Vanar is trying to make transaction costs feel boring in the best way, predictable in dollar terms instead of swinging with the token price. That sounds simple until you ask what has to happen behind the scenes. The protocol needs a way to translate a moving token price into a stable USD fee target. In Vanar’s own materials, that translation is described as a process where the foundation calculates the price using multiple sources and then updates the fee parameters. Once you do that, fees stop being just a market outcome. They become a controlled setting.

And controlled settings always have consequences. If the update process is slow, inaccurate, or biased, the network can drift into a mode where it is accidentally too cheap or accidentally too expensive. Too cheap invites spam and low value activity that eats resources. Too expensive pushes out real usage and turns the chain into a place only certain apps can afford. Even if the people running the process act in good faith, the simple fact is this: whoever shapes the fee update loop shapes what kinds of behavior become rational inside the ecosystem.

That matters even more because Vanar is also trying to make onchain data feel usable, not just stored. Its stack talks about Neutron as a way to compress and structure data into compact onchain objects, and Kayon as a logic layer for richer onchain behavior. The technical claim is that the chain can hold more context, more memory, more of the stuff agents need, without the usual cost explosion. The human way to say it is: Vanar wants the chain to remember things cheaply, so builders do not have to rent memory from offchain services every time they want an app to act intelligently.

But cheap and predictable memory changes incentives fast. If it is easy to push data onchain and query it repeatedly, people will do it. Some of it will be valuable. Some of it will be noise. And the chain has to decide how it prices that activity when it is committed to keeping fees stable. On networks where fees float freely, congestion can price itself out. On a network trying to keep a stable fee target, congestion has to be handled through resource rules, limits, and policy choices. That is where design meets politics. Because the moment you are not letting a fee market do all the sorting, you are deciding, explicitly or implicitly, what kinds of usage you want to prioritize.

Now look at how validators get paid, because that is the backbone of any chain that wants low and stable user fees. Vanar’s documents describe a long emission schedule with most new issuance directed to validator rewards, plus a separate stream aimed at development and community incentives. The simplest way to read that is: security and ecosystem growth are funded mostly by inflation, not by extracting high fees from users. In the early years, that can feel smooth. Validators have a reliable income stream, builders can be supported, and users do not get punished by fee spikes.

The tradeoff is who wins over time. In inflation funded systems, the people who actively stake and participate are the ones who stay whole. Passive holders slowly give up share. This is not moral, it is mechanical. And if the network links reward capture to active involvement in validator selection or governance, the advantage tilts even more toward organized participants. Funds, professional delegators, and validator groups can do the work consistently. Most normal holders will not. Over years, that difference compounds into influence.

The early validator setup matters too. Vanar describes an initial phase where the foundation runs validators, with a longer term plan to open participation through reputation and community choice. That is a practical launch strategy if you care about reliability and want to attract partners who cannot tolerate chaos. But it also sets the tone of the ecosystem. Early on, the chain behaves less like a wild open market and more like a managed platform. Builders and liquidity providers adapt to that reality. They build relationships around it. And if decentralization expands later, it does not erase that history. It just overlays more participants onto an existing power map.

Liquidity is another quiet pressure that people underestimate. Vanar’s materials talk about wrapped versions and bridging, which is how tokens travel and how liquidity forms across different environments. The economic wrinkle is that price discovery tends to live where liquidity is deepest. If the token is thinly traded, it becomes easier to move and harder to measure cleanly. In a system where token price influences fee parameters, shaky price discovery can turn into shaky fee settings. Even small lags or update windows can create moments where heavy users benefit by timing resource intensive actions when the network is underpricing them relative to real market conditions. Again, not drama. Just incentives doing what incentives do.

Then there is the development rewards stream, which functions like a built in budget. That can be a strength because it funds builders without relying on random donations or purely fee driven treasuries. But it also becomes a power center. Whoever controls distribution criteria can shape which teams survive and what kinds of products become the default culture of the chain. Over time, this can matter as much as the validator set, because it decides what gets built and what never gets a chance.

So when you zoom out, the story becomes less about AI as a buzzword and more about control systems. Vanar is trying to hold several things steady at once: predictable user costs, a data and memory oriented base layer, and a security model funded largely by emission. That combination can work, but it forces the chain to answer three hard questions in a way most networks never have to.

The first is how to make the fee stabilization loop feel neutral and resilient, not like a policy dial held by a small group. The second is how to price data and computation honestly when the chain is committed to stable fees and invites memory heavy usage. The third is how to make the transition from foundation run validation to broader participation real, not symbolic, because the longer early control structures stay in place, the more they become the ecosystem’s default.

If the next market cycle brings more users and more pressure, the real test will be whether Vanar can keep its promise of predictability without concentrating too much influence in the same hands that maintain that predictability. The design changes that would matter most are not flashy. They are governance and mechanism changes: decentralizing the inputs that drive fee updates, tightening resource accounting for memory and compute heavy workloads, and setting clear, measurable decentralization milestones for validator selection and decision making.

If those pieces evolve well, Vanar could end up with a very specific kind of internal economy: builders can plan, users are not constantly priced out, and the chain’s memory features become a practical advantage instead of a subsidy magnet. If they do not, the risk is a network that stays efficient but becomes politically brittle, where predictability depends on a small circle, and where the benefits of participation concentrate while the rest slowly lose influence.