When I think about token economics in decentralized infrastructure, I try to ignore price charts entirely. They are noisy, emotional, and usually irrelevant to whether a system can survive five or ten years. What matters more to me is something quieter: who is rewarded for staying, who is tempted to leave, and how the protocol distinguishes between the two without relying on trust.

Walrus, through the WAL token, takes a noticeably deliberate position on this question. Its economic design does not try to make everyone happy at once. Instead, it draws a clear line between participants who commit resources over long horizons and those who participate opportunistically. Understanding that distinction is essential to understanding how Walrus aims to remain functional over time rather than merely active.

This article is my attempt to unpack that logic carefully, without hype, and without assuming that incentives magically work just because a token exists.

The Core Tension: Persistence vs. Liquidity

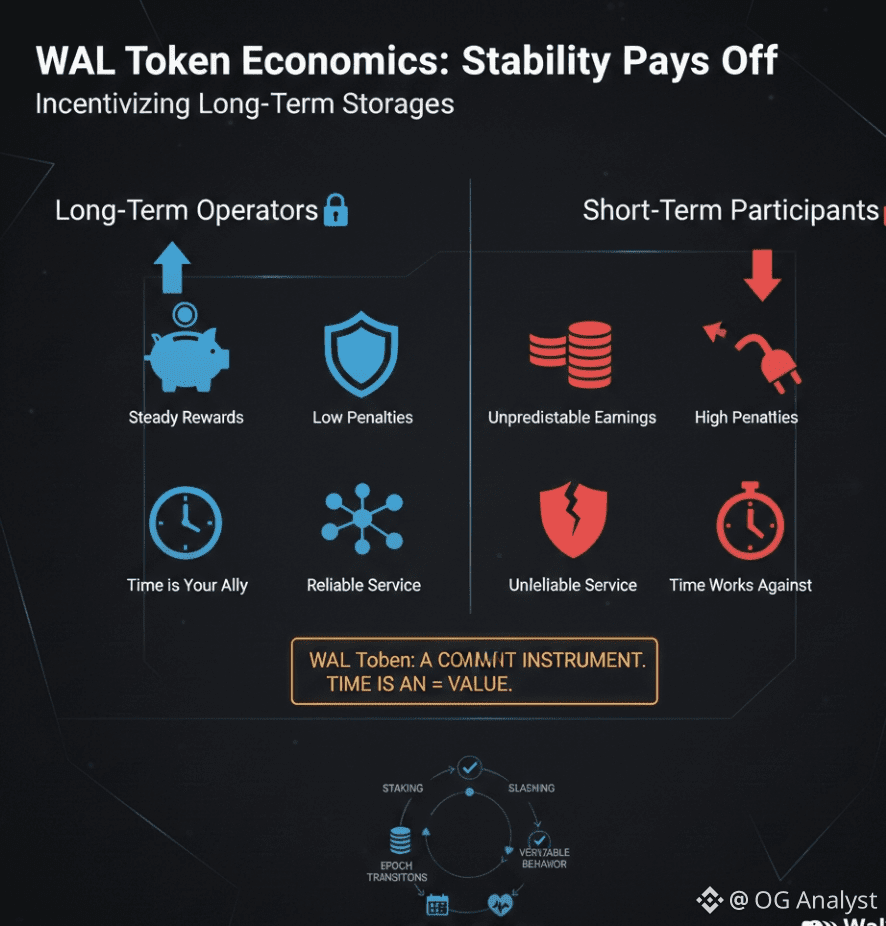

Every decentralized storage system faces a fundamental tension. On one side are long-term storage providers—operators who invest in hardware, bandwidth, monitoring, and operational discipline. On the other side are short-term participants—those who are willing to participate only when returns are immediately attractive or risks are minimal.

Both are rational actors. But they contribute very different kinds of value.

From the perspective of the network, persistent storage providers create reliability, while short-term participants create elasticity. Walrus does not try to eliminate either group. Instead, WAL token economics are structured to differentiate rewards based on behavior over time, not just momentary participation.

That distinction is subtle, but it runs through the entire system.

WAL as a Commitment Instrument, Not Just a Reward Token

The first thing I noticed when examining WAL is that it is not treated merely as a payment token. WAL functions as a commitment instrument.

Storage providers must stake WAL to participate meaningfully in the network. This stake is not symbolic. It is directly tied to responsibility. If a node fails to meet availability requirements or attempts to misrepresent stored data, its stake becomes a liability rather than an asset.

This immediately changes the calculus. Long-term providers, who expect to operate reliably over many epochs, can amortize the risk of staking across time. Short-term participants cannot. For them, staking WAL introduces downside that is difficult to justify if their intention is to extract value quickly and exit.

In this way, WAL naturally favors participants who plan to stay.

Time as an Economic Filter

One of the most underappreciated design choices in Walrus is how it uses time itself as a filtering mechanism.

Rewards in Walrus are not simply paid for joining the network or for a single successful action. They are tied to ongoing behavior across epochs—periods during which nodes are expected to store data, respond to challenges, and remain available.

A short-term participant may earn some rewards initially, but they face a problem: their risk accumulates faster than their reputation. Each additional epoch increases the probability that failure, downtime, or misbehavior will result in penalties.

Long-term providers, by contrast, benefit from consistency. Over time, predictable behavior becomes economically dominant. WAL does not need to explicitly label someone as “long-term” or “short-term.” The economics do that implicitly.

Storage Rewards Are Structured Around Responsibility, Not Volume Alone

In many systems, rewards scale primarily with raw capacity. The more you store, the more you earn. Walrus takes a more nuanced approach.

While capacity matters, WAL rewards are also tied to correct storage behavior, including:

Maintaining availability

Responding to verification challenges

Participating correctly in epoch transitions

Preserving data integrity across failures

This means that simply showing up with capacity for a short time is not enough to maximize rewards. Operators who remain through reconfigurations and churn events—moments when systems are most stressed—are implicitly more valuable.

From an economic standpoint, this tilts incentives toward operators who are willing to invest in operational resilience rather than just raw scale.

Slashing Risk Discourages Opportunistic Participation

Slashing is often described in abstract terms, but its psychological effect is concrete. WAL staking introduces real downside risk for misbehavior or negligence.

Short-term participants tend to underestimate this risk. They often assume they can exit before penalties materialize. Walrus makes that assumption dangerous by designing slashing conditions that are:

Triggered by provable behavior, not subjective judgment

Enforced automatically through protocol rules

Aligned with data availability guarantees

For long-term operators, slashing is a manageable risk. They build monitoring, redundancy, and operational discipline to minimize it. For short-term participants, slashing is unpredictable and therefore unattractive.

Again, the protocol does not ban short-term actors. It simply makes long-term reliability the dominant strategy.

Epoch Transitions Reward Stability

One of the moments where token economics become most visible is during epoch transitions. These are periods when committees change and responsibilities are reassigned.

Walrus is designed so that data remains available throughout these transitions, but that continuity depends heavily on nodes that behave correctly during reconfiguration.

Economically, this matters because nodes that exit prematurely or behave inconsistently around epoch boundaries face lost rewards or penalties. Nodes that remain stable through transitions accumulate a history of correct participation.

Over time, WAL rewards favor operators who treat storage as an ongoing service rather than a series of disconnected opportunities.

WAL Incentives Are Asymmetric by Design

Something I find particularly interesting is that WAL incentives are asymmetric. Upside is gradual, but downside can be sudden.

This asymmetry is intentional. It mirrors real infrastructure economics. Building trust takes time; losing it can happen quickly.

For long-term providers, this asymmetry is acceptable. They expect slow, steady returns in exchange for predictable operation. For short-term participants, the same structure feels hostile, because it punishes mistakes more than it rewards brief success.

In effect, WAL economics encode a value judgment: reliability matters more than opportunism.

No Guaranteed Yield for Passive Holding

Another subtle but important point is that WAL does not promise passive yield simply for holding tokens. Rewards are tied to active, verifiable participation.

This discourages speculative short-term behavior that seeks yield without contribution. Long-term storage providers, by contrast, naturally engage in the activities required to earn rewards, because those activities align with their operational goals.

This design reduces the gap between economic incentives and network health. WAL is earned by doing the work the network actually needs.

Why Short-Term Participants Still Exist

Despite all this, Walrus does not eliminate short-term participants. Nor should it.

Short-term actors provide liquidity, experimentation, and early participation. They test assumptions and expose weaknesses. WAL economics allow their presence but limit their influence.

Short-term participants can earn rewards, but they cannot extract disproportionate value without taking on long-term risk. This keeps the system flexible without allowing it to be hollowed out.

From a systems perspective, this balance feels intentional rather than accidental.

WAL as a Signal of Intent

Over time, WAL staking becomes less about financial exposure and more about signaling intent.

A large, persistent stake signals that an operator plans to remain accountable. A small or fleeting stake signals experimentation or opportunism. The protocol does not judge these signals morally—but it prices them differently.

This is, in my view, one of the most honest uses of token economics. WAL does not pretend that all participants are equal. It recognizes that intent matters, and it allows the market to express that intent through risk.

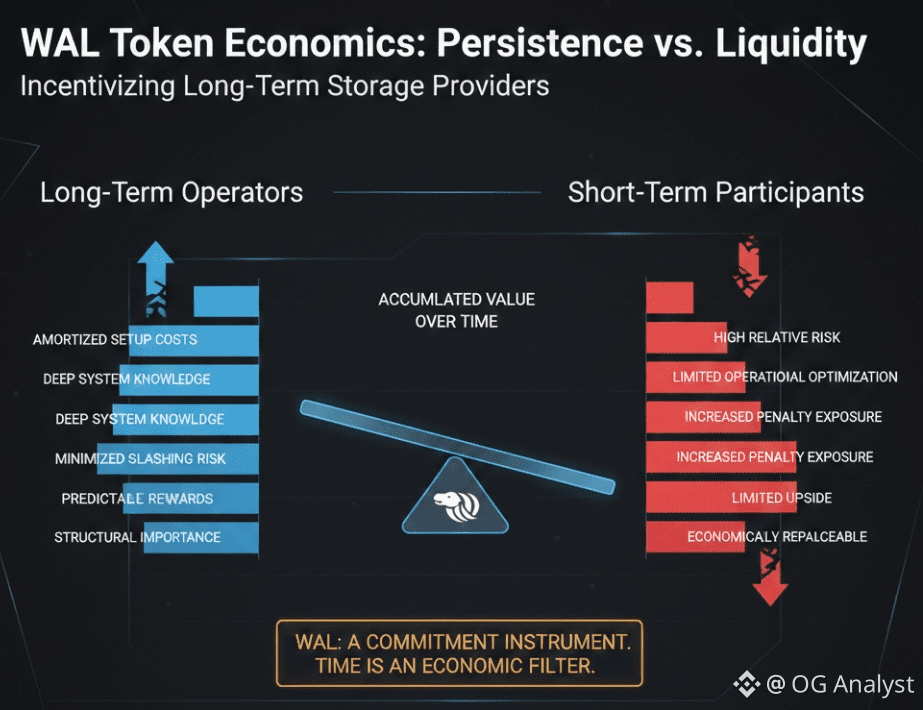

Comparing Long-Term and Short-Term Outcomes

If I imagine two operators—one committed for years, one present for weeks—the difference in outcomes becomes clear.

The long-term operator:

Amortizes setup costs

Learns system behavior deeply

Minimizes slashing risk

Accumulates predictable rewards

Becomes structurally important to availability

The short-term participant:

Faces high relative risk

Cannot optimize operations fully

Is more exposed to penalties

Earns limited upside

Remains economically replaceable

WAL token economics do not force this outcome. They simply allow it to emerge.

A Broader Reflection on Infrastructure Tokens

Looking beyond Walrus, I think many infrastructure tokens fail because they reward activity without commitment. They confuse participation with contribution.

WAL avoids that trap by anchoring rewards to time, responsibility, and verifiable behavior. It does not promise excitement. It promises alignment.

That may not attract everyone—but it attracts the participants who matter most for long-term storage.

Conclusion

WAL token economics incentivize long-term storage providers not through marketing or artificial lockups, but through structural alignment between responsibility and reward. Staking, slashing, epoch-based participation, and continuous verification all increase the relative attractiveness of persistent, reliable operation.

Short-term participants are not excluded, but they are economically constrained. They can participate, experiment, and even earn—but they cannot dominate without accepting the same risks as long-term providers.

In my view, that is not a flaw. It is the point.