@Walrus 🦭/acc Most people think “storage” is a quiet problem until it suddenly becomes a loud one. A file doesn’t load. A dataset link dies. An application that felt solid starts behaving like it’s standing on missing floorboards.

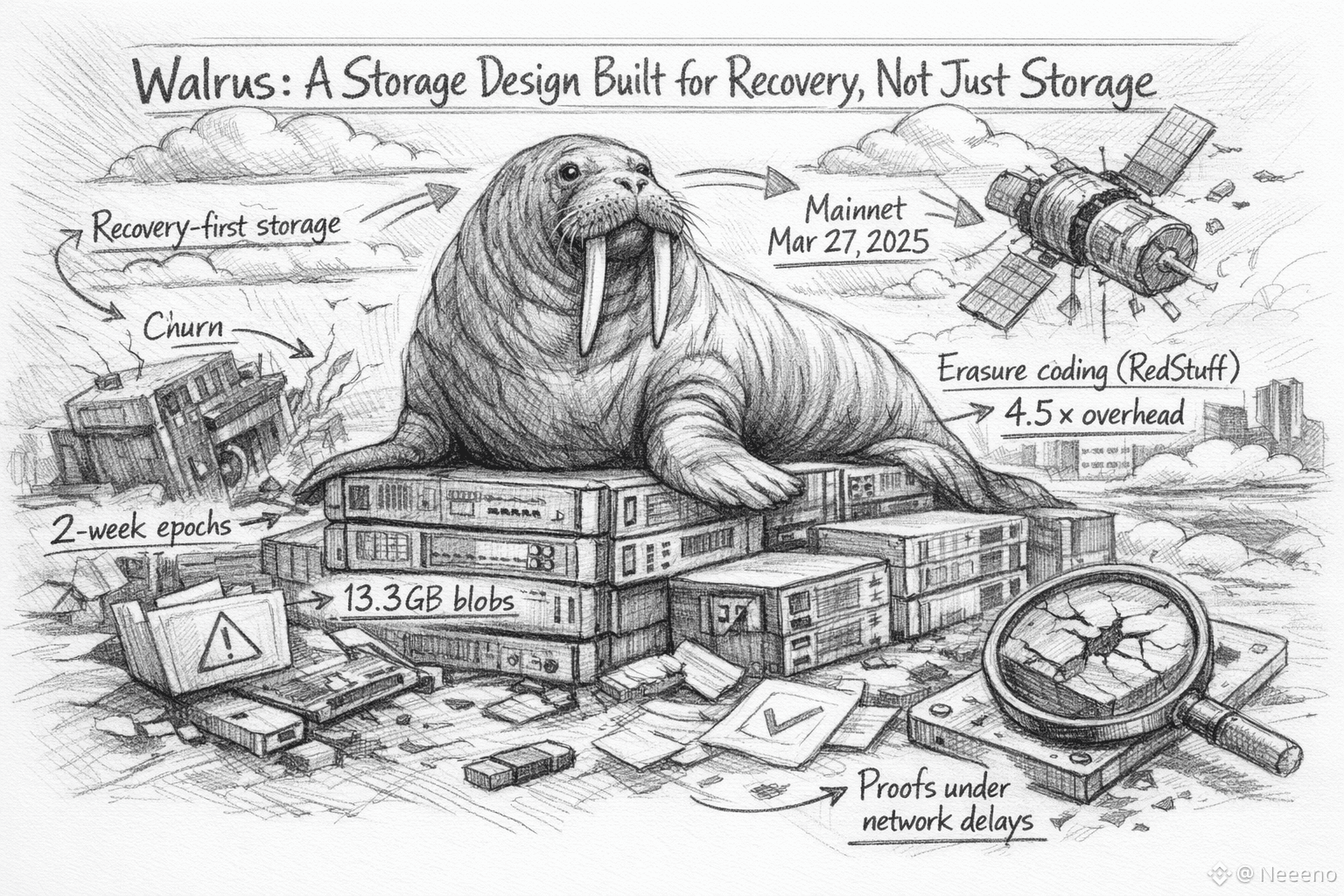

When storage breaks, it creates a real-world problem, not just a software one. Someone made a promise, and it didn’t hold. That’s the feeling Walrus is built around, in my view. It doesn’t read like a project obsessed with hoarding data. It reads like a design obsessed with recovery—what happens when nodes churn, when networks get messy, and when the world refuses to behave politely.

The timing is a big part of why this topic is trending now. We’re living through a shift where more products treat data as living material, not static files. AI workflows lean on large blobs—datasets, model artifacts, media libraries. Games and consumer apps want content to load fast and stay available, but they also want the freedom to move between platforms without a single hosting provider holding the keys. Even in crypto, more of the “real” value lives off-chain: the images, the proofs, the records, the large objects that contracts reference but cannot contain. Walrus positions itself right in that tension: storage that is meant to survive churn, not just look decentralized on paper. When it launched on public mainnet on March 27, 2025, it wasn’t just another milestone announcement—it was the date the system volunteered to be judged by behavior, not intent.

The project’s roots also matter. Walrus was developed as Mysten Labs’ second major protocol after Sui, and it leans into that world: a storage network that plugs into an ecosystem already thinking about throughput, consumer-grade experiences, and programmable coordination.You can feel the difference between a storage idea designed for whitepapers and one designed for apps that ship. It’s not only about “can I store a thing,” but “can I store a big thing, can I keep it available, and can I prove it’s being kept without pretending the internet is always honest.”

A few concrete details show what “built for recovery” means in practice. Walrus’ docs note a current maximum blob size of 13.3 GB, which quietly signals the target audience: real media, real datasets, real app payloads—not tiny demo files. The network also works in epochs, with mainnet using a two-week epoch duration.That cadence is important because recovery isn’t a one-time event. It’s a recurring reality. Systems like this need a rhythm for membership changes, incentives, and accountability that doesn’t collapse every time operators come and go.

Under the hood, Walrus leans on a centerpiece idea called RedStuff, a two-dimensional erasure coding design. The headline number that keeps coming up is the replication factor: roughly 4.5x for high security, rather than brute-force full replication everywhere. If you’re new to storage economics, that number might sound high. If you’ve spent time around decentralized storage trade-offs, it can actually feel like a disciplined compromise: expensive enough to be resilient, restrained enough to be usable, and structured so that recovery bandwidth scales with what was lost rather than forcing an overreaction every time a few nodes disappear The deeper point isn’t the exact multiplier. It’s the posture: assume churn, assume partial loss, and treat repair as normal maintenance rather than an emergency hack.

That posture shows up again in how Walrus frames verification. A recurring failure mode in decentralized storage is the “prove without storing” temptation—systems where adversaries can game challenges under network delays or partial availability. The Walrus paper argues that RedStuff is designed to support storage challenges even under asynchronous network conditions, to reduce the space for those games. I’m always cautious about grand claims here, but I do think the focus is telling. A storage network isn’t just competing on “cost per gigabyte.” It’s competing on whether the incentives and proofs still mean something when the network is stressed, not when it’s calm.

Another reason Walrus is getting attention is the money and the narrative force behind it. Ahead of mainnet, reporting noted a $140 million token sale, which put a spotlight on the project and made it harder to dismiss as a niche experiment. Funding alone doesn’t make infrastructure real, but it does change expectations. When large capital enters the room, the conversation shifts from “interesting tech” to “will this hold up, and who will use it first?” That’s why you see coverage tying Walrus to gaming and consumer applications—areas where storage failures are felt immediately, not debated abstractly

Token design is also part of the recovery story, because incentives are what keep operators showing up after the novelty fades. Walrus frames WAL as the payment token for storage, with a mechanism intended to keep storage costs stable in fiat terms and to distribute prepaid storage revenue over time to nodes and stakers. That detail matters more than people admit. If storage pricing whipsaws with token volatility, builders either overpay for safety or underpay and get fragility. A “stable-in-fiat” goal is basically an attempt to make storage feel like a utility, not a casino.

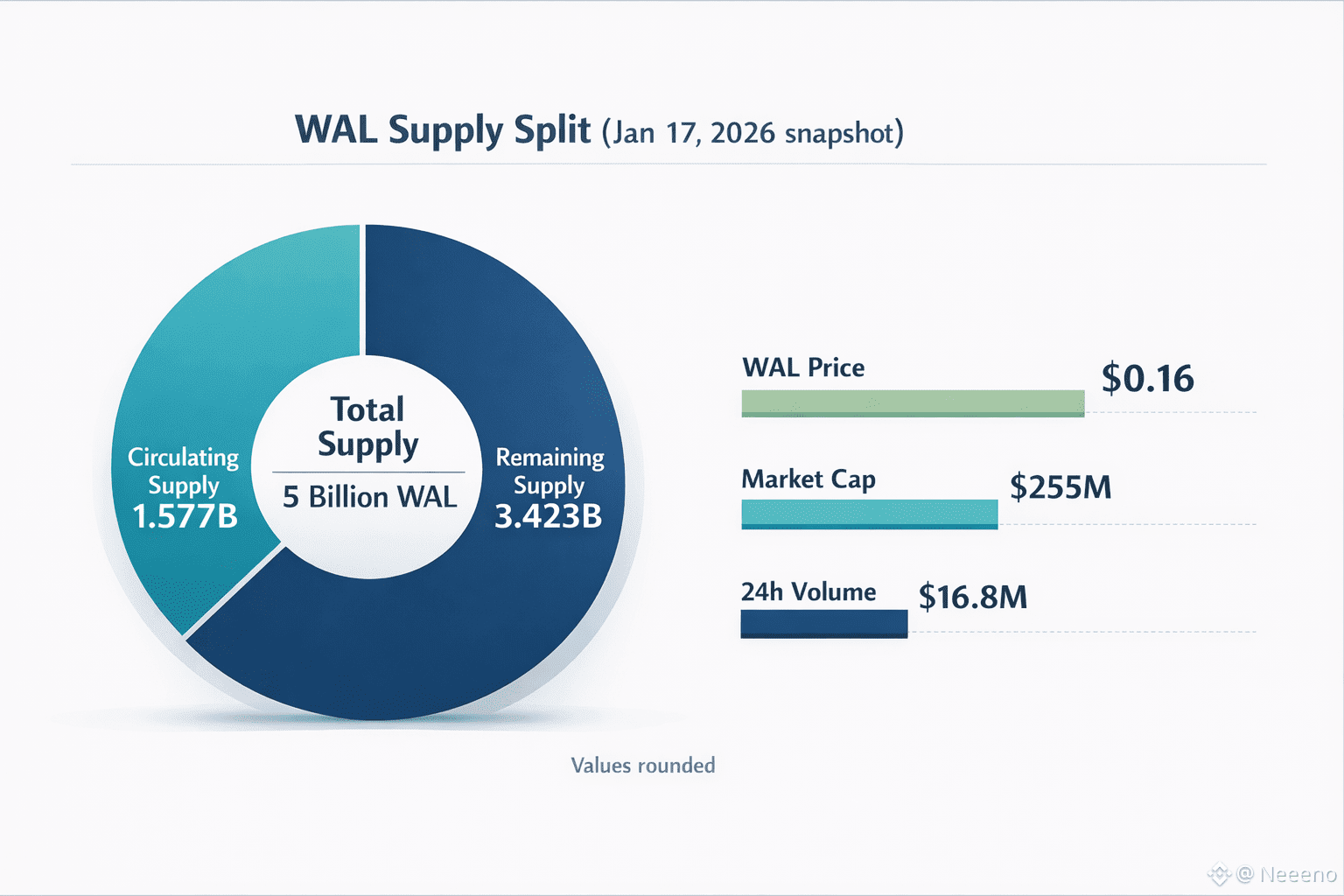

And yes, the market data is part of why this topic keeps resurfacing. As of January 17, 2026, CoinMarketCap showed WAL around $0.16 with a circulating supply about 1.577B out of a 5B max supply, and a market cap around $255M (with roughly $16.8M 24h volume at the time). Those numbers don’t prove product-market fit, but they do explain attention. A network with that level of valuation and liquidity becomes something builders, investors, and competing ecosystems feel they need to have an opinion on.

So what does “built for recovery” really mean as a conclusion, beyond the technical nouns? It means designing for the unpleasant middle of reality: nodes leave, disks fail, networks delay, incentives drift, and users still expect their data to come back intact. Walrus is interesting because it treats those conditions as the default environment, not as edge cases. It’s not trying to romanticize storage. It’s trying to make it dependable enough that nobody has to think about it—until the day something goes wrong, and recovery is the difference between an outage and a shrug. If this design holds up over the next couple of years, the real win won’t be hype. It will be a quiet shift in what builders assume is possible: storage that doesn’t just exist, but reliably returns.