When I first explored how Walrus handles long-term storage payments, I realized this is one of those deceptively complex problems that many decentralized storage systems overlook. It’s easy to take a payment upfront and assume the job is done—but in reality, storing data for months or years requires continuous effort from node operators. If compensation is front-loaded, there’s little incentive for operators to maintain high availability over time.

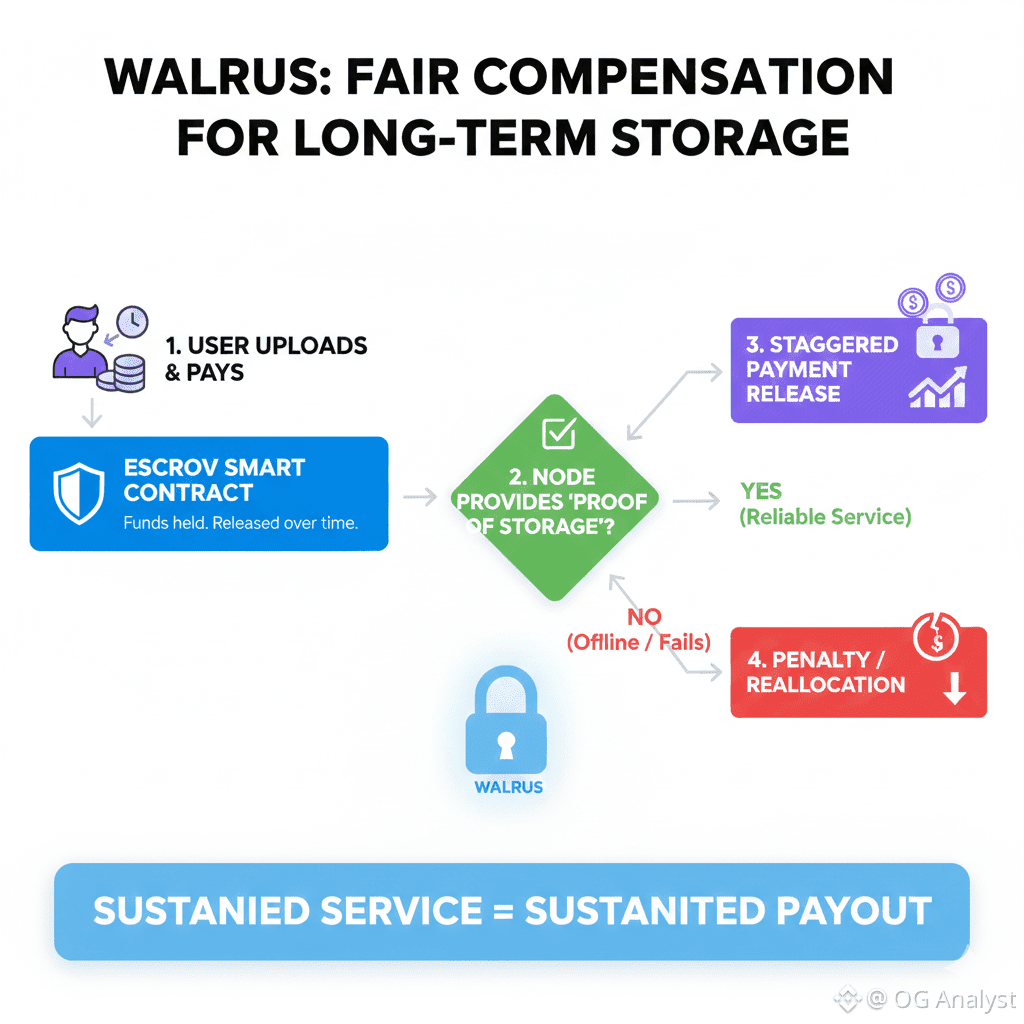

Walrus approaches this challenge with a combination of escrowed funds, smart contract logic, and continuous verification, creating a system where node operators are rewarded for ongoing service rather than just the initial upload. Let me walk you through how this works and why it matters.

The Upfront Payment Problem

In many traditional systems, users pay a lump sum to store data. This works fine if the provider is centralized and bound by legal contracts, but in decentralized storage, trust is distributed and nodes operate autonomously. If a node receives full payment upfront, nothing technically prevents it from going offline once the upload is complete, leaving users with inaccessible files.

From my perspective, this scenario highlights a tension between economic incentives and reliability. Any robust decentralized system must ensure that operators are compensated in a way that aligns with actual service provision over time. Walrus does exactly this by escrow design.

Escrow Mechanism in Walrus

When a user uploads data and pays in WAL for long-term storage, the funds do not immediately transfer to the storage node. Instead, they are held in an on-chain escrow smart contract. This serves several purposes:

1. Security and accountability: Operators cannot access the full payment until they demonstrate that the data is continuously available and verifiably stored.

2. Time-staggered release: Payments are gradually released over the duration of the storage contract, often in predefined intervals, corresponding to verified uptime and availability checks.

3. Protection against failures: If a node goes offline or fails to respond to storage challenges, the escrowed funds are reduced proportionally or reallocated to nodes that maintain proper service.

I find this approach particularly elegant because it doesn’t rely on trust in any individual operator; the system itself enforces fairness.

Proofs of Storage and Verification

The release of funds is tied to availability proofs generated by the node. Every period, the node must demonstrate it still holds the correct data using cryptographic proofs. These can include challenges for specific data shards or more complex mechanisms like erasure-coded validation.

From a reflective standpoint, this design effectively aligns the incentives of the node operator with the needs of the user. If the operator fails the proof or misses the verification window, they forfeit some of the escrowed funds. Conversely, consistent performance translates into a steady, predictable income. It’s a system that treats reliability as a first-class asset, not a side effect.

Time-Based Release Logic

The staggered payment mechanism is more than just a check; it’s a way to model service continuity over time. Typically, the smart contract divides the total payment into intervals—daily, weekly, or monthly—based on the agreed storage duration.

At each interval, the contract evaluates node performance via availability proofs.

Successful verification triggers partial release of the escrowed WAL.

Failure or downtime either delays payment or reduces it according to a penalty structure.

I appreciate how this mirrors real-world service agreements: you don’t pay for promises—you pay for consistent delivery.

Handling Disputes and Redundancy

No decentralized system is immune to edge cases. Nodes could claim they have data when network issues prevent verification, or disputes could arise over partial data loss. Walrus anticipates these scenarios with multi-layer checks:

Multiple nodes storing redundant shards allow cross-validation.

Smart contracts can incorporate dispute-resolution logic, enabling users to reclaim escrowed funds or redirect them to backup nodes.

Reputation tracking ensures that nodes with repeated verification failures gradually lose trust and delegation.

For me, this approach stands out because it treats storage not just as a technical problem but as a socially-mediated system where incentives, accountability, and reputation interact.

Human-Centric Reflection

What strikes me most about Walrus’s escrow system is how it reflects human thinking in decentralized design. Instead of relying solely on cryptography or blockchain rules, it models incentives the way a responsible manager would: pay for outcomes, not promises; penalize poor performance; reward consistent reliability.

This makes the system understandable, predictable, and approachable for users who may not be deeply technical. From a user’s perspective, they can see that their data is protected, that payments are tied to service, and that there is accountability without requiring them to police every node manually.

Broader Implications

In my view, this payment structure also has broader implications for the decentralized storage ecosystem:

It encourages long-term commitment from node operators, which is crucial for sustainability.

It reduces the risk of opportunistic behavior, such as nodes taking payment and disappearing.

It provides economic predictability for operators, helping the network attract reliable participants rather than speculative actors.

Effectively, Walrus transforms storage into a living service economy, where trust, performance, and compensation are continuously aligned.

Conclusion

By combining escrowed payments, staggered release schedules, and availability proofs, Walrus ensures that node operators are paid for actual ongoing storage service rather than a one-time upload. This design elegantly balances trustless decentralization with practical human behavior, rewarding reliability, and penalizing failures.

For me, this approach represents a mature understanding of incentives in decentralized networks. It shows that sustainable storage is not just about technology—it’s about creating a system where economics, accountability, and service converge in a way that protects users while fostering operator participation.

The result is a network where long-term storage is both reliable and fairly compensated, giving participants confidence that Walrus is designed not just to store data, but to sustain it responsibly over time.