Working with decentralized storage systems quickly teaches you that durability is not just a technical problem. It is an economic one, a network one, and often a human one. The moment you remove central control, assumptions that worked fine in data centers start breaking down. Walrus Protocol stood out to me because it does not try to patch these cracks with more rules or more replication. It questions the model itself.

1. Why decentralization makes durability harder than it looks

In a decentralized environment, storage nodes are not owned by a single operator. They are run by independent participants who are incentivized economically but not inherently trustworthy.

From experience, this raises an immediate question. How do you ensure nodes actually keep the data once they are paid?

Most existing systems answer this with continuous challenges and proofs of storage. Nodes must regularly prove they still hold the data. On paper, this sounds reasonable. In practice, it creates a fragile system.

2. The hidden cost of constant verification

Frequent proofs of storage assume a lot about the network. They assume low latency, frequent connectivity, and relatively synchronous behavior. Anyone who has operated systems across continents knows how unrealistic this is.

These mechanisms also consume bandwidth continuously, even when nothing is going wrong. Over time, the verification traffic can rival or exceed the cost of storing the data itself.

This leads to another uncomfortable question. Are we building storage systems, or are we building monitoring systems that happen to store data on the side?

3. The replication mindset and its limitations

Most decentralized systems still treat durability as a quantity problem. The logic is simple. More copies mean more safety.

But in real deployments, replication brings its own problems.

More replicas mean higher storage costs for node operators.

Higher costs mean higher incentives are required.

Higher incentives attract participants, but not necessarily reliable ones.

This feedback loop often results in systems that are expensive to maintain and difficult to reason about at scale.

4. Walrus asks a different question

What caught my attention with Walrus was that it does not start by asking how many copies of the data exist. Instead, it asks how much information is actually required to recover the data.

This shift sounds subtle, but it changes everything. Durability stops being about duplication and starts being about information theory.

5. Erasure coding as a first-class design choice

Walrus replaces heavy replication with advanced erasure coding. Data is encoded into fragments in such a way that the original content can be reconstructed even if a large portion of those fragments disappears.

From hands-on experience, this has two major implications.

The system no longer depends on any specific node.

Temporary or permanent node failures become expected, not catastrophic.

Durability is enforced mathematically, not socially or operationally.

6. Reduced reliance on constant challenges

Because Walrus does not require every fragment to remain available at all times, it reduces the pressure to constantly check every node. The system tolerates loss by design.

This raises an important question. If data recovery does not depend on perfect behavior, how often do we really need to verify storage?

In practice, this leads to fewer challenges, lower bandwidth consumption, and a system that is better aligned with real-world network conditions.

7. Trustlessness without fragility

One of the hardest things to balance in decentralized systems is trustlessness without overengineering. Walrus manages this by accepting that nodes will fail, disconnect, or behave unpredictably.

Instead of trying to force ideal behavior through constant proofs, it designs around imperfect behavior. This is closer to how global networks actually operate.

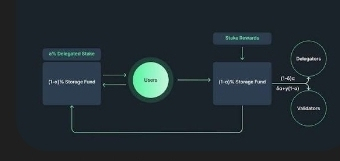

8. Economic implications for node operators

Another aspect that becomes clear over time is the economic impact. Storing erasure-coded fragments is cheaper than storing full replicas. Lower storage overhead means lower operating costs for nodes.

Lower costs reduce the pressure to extract maximum short-term profit, which in turn improves long-term participation. This is not a guarantee, but it is a healthier starting point.

9. A durability model built for reality

Walrus does not claim that decentralization is easy or that failures disappear. What it does is align durability with reality instead of fighting it.

By focusing on how little information is required to recover data, rather than how many copies exist, Walrus reframes durability as an information problem. From real experience, this approach feels more sustainable, more scalable, and more honest about how distributed systems actually behave over time.