If blockchains are the courts of digital truth, then data is the evidence. And Web3 has been running trials with evidence stored in the wrong building: centralized servers, brittle links, and “trust me bro” content delivery. Walrus is a blunt fix to a delicate problem—store and serve large binary objects (blobs) with strong integrity and availability guarantees, without forcing every validator on a Layer 1 to carry the full weight of everyone’s files. Walrus does this by splitting unstructured blobs into smaller pieces (“slivers”) and distributing them across storage nodes, so the original data can be reconstructed even when a large portion is missing. The developer docs describe recovery even when up to two-thirds of slivers are missing, while keeping replication down to ~4x–5x.

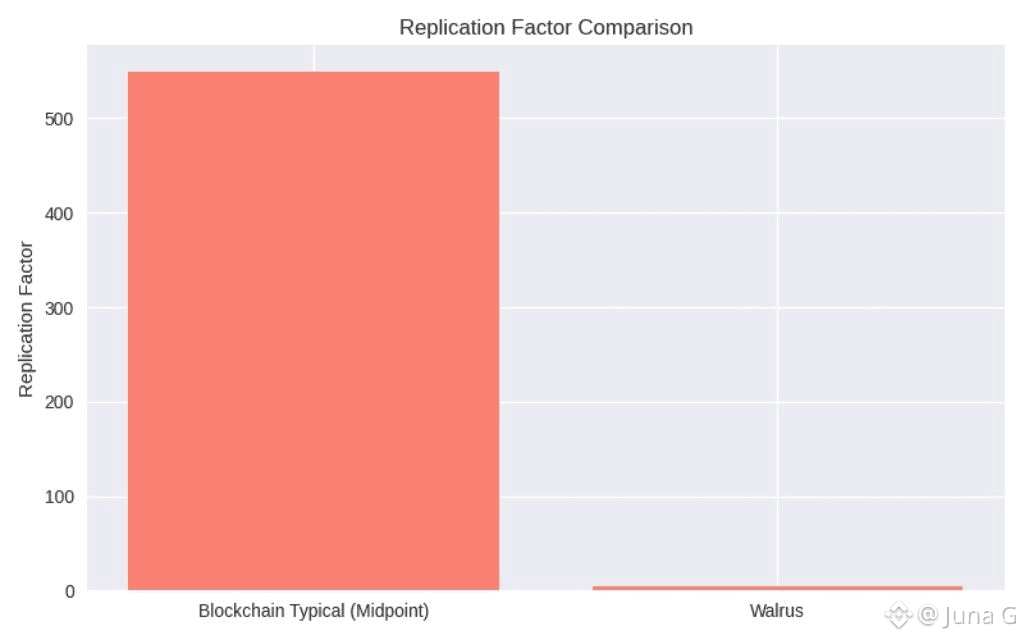

The “why now” is obvious if you’ve watched modern dapps mature. NFTs, media-heavy social, rollups needing data availability, AI provenance, and even software supply-chain auditing all demand durable, verifiable storage. The Walrus whitepaper frames this in a pragmatic way: blockchains replicate state machine data at massive overhead (100–1000x replication factors are common when you count the validators), and that’s sensible for computation, but wildly inefficient for blobs that aren’t computed upon. Walrus positions itself as the missing utility layer: high-integrity blob storage with overhead that doesn’t explode as networks scale.

Under the hood, Walrus isn’t just “another storage network.” The whitepaper introduces Red Stuff, a two-dimensional erasure coding approach designed to balance security, recovery efficiency, and robustness under churn. It reports a 4.5x replication factor while enabling “self-healing” recovery bandwidth proportional to only the lost data, rather than the full blob, and it’s designed to support storage challenges in asynchronous networks—an important detail because real networks don’t behave like tidy lab clocks. That’s the kind of engineering choice that matters if you want storage to graduate from hobbyist infra to something institutions can quietly rely on.

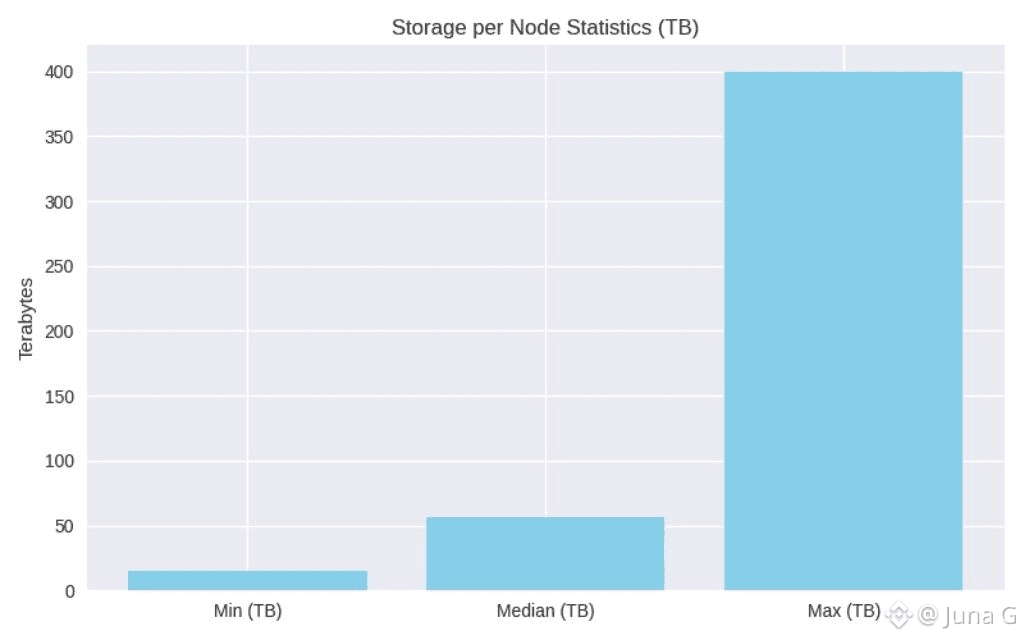

Scalability isn’t marketed as a vibe; it’s treated as an operational parameter. Walrus is engineered to scale horizontally to hundreds or thousands of storage nodes, and it’s already been evaluated in a decentralized testbed: 105 independently operated storage nodes coordinating 1,000 shards, with nodes spanning at least 17 countries. In that environment, shard allocation is stake-weighted (mirroring the mainnet deployment model), and the paper reports storage per node ranging from 15 to 400 TB, with a median of 56.9 TB. When you combine that distribution with erasure coding, you get a storage fabric that doesn’t depend on “a few big hosts” behaving; it becomes an ecosystem.

Interoperability is where Walrus quietly separates itself from “storage-as-a-silo.” Walrus uses Sui as a secure control plane for metadata and proofs-of-availability (PoA) certificates, but the product story is explicitly chain-agnostic: builders can bring data from ecosystems like Solana and Ethereum using developer tools and SDKs, and projects of many architectures can integrate Walrus for blob storage. The deeper point is that Walrus treats data as portable infrastructure. If you can verify it and fetch it, it can serve apps regardless of where the execution happens. That’s a credible path to becoming “the storage layer” without demanding ideological purity from developers.

Now the part most people underestimate: tokenization in Walrus isn’t a sticker on top; it’s embedded into the product’s ergonomics. Walrus explicitly models blobs and storage resources as objects on Sui, making storage capacity something that can be owned, transferred, and composed inside smart contracts. That’s a subtle but profound shift: storage stops being a background cost and becomes a programmable asset.

You can automate renewals, build escrow-like storage agreements, create metered access patterns, and design data marketplaces where datasets have enforceable lifecycle rules. When people say “data is the new oil,” Walrus is basically building the refinery controls.

The native token $WAL is how the economics become legible and enforceable. WAL is the payment token for storage, and the mechanism is designed to keep storage costs stable in fiat terms while smoothing out WAL price fluctuations. Users pay upfront to store data for a fixed time, and those payments are distributed across time to storage nodes and stakers as compensation. That upfront-to-streamed distribution matters because it can align long-lived storage obligations with long-lived incentives, rather than creating a “pay once, hope forever” tragedy.

Walrus also acknowledges the early bootstrap problem and bakes in an adoption lever: a 10% token allocation for subsidies intended to help users access storage below the current market price while supporting viable business models for storage nodes. In other words, the network is willing to spend to seed usage, but it does so through a model that still compensates operators and keeps the protocol financially coherent.

Governance, in Walrus, is not about arguing on a forum; it’s about tuning the machine. The WAL token anchors governance over key parameters, including penalties, with node votes weighted by WAL stake. The design logic is refreshingly practical: nodes bear the cost of others’ underperformance (think data migration and reliability), so they’re incentivized to calibrate penalties that keep the system healthy. The protocol also discusses deflationary pressure through burning mechanisms tied to negative externalities: short-term stake shifting (which can force expensive data migration) can incur penalty fees that are partially burned, and future slashing of low-performing nodes would also burn a portion of slashed amounts.

Put together, Walrus is building a world where data isn’t an afterthought bolted to compute—it’s a first-class, governable resource. The novelty is not “storage on chain.” The novelty is programmable, verifiable, economically-aligned storage that can serve entire ecosystems, survive adversarial conditions, and still feel like a developer-friendly primitive. That’s why the most interesting Walrus question isn’t “can it store files?” It’s “what happens when storage becomes composable like tokens?” The answer is: you stop renting your reality from centralized clouds, and you start owning it—contract by contract, blob by blob. This is not financial advice; it’s an architecture thesis worth watching, especially if you care about $WAL’s role in how #Walrus prices, secures, and governs that thesis.