Decentralized storage is often treated like a solved problem in Web3. Data gets uploaded, split across nodes, replicated for redundancy, and the discussion usually ends there. But anyone who has shipped a real on-chain application knows that this framing is incomplete. Stored data is not the same as usable data, and in practice, the difference shows up at the worst possible time.

The uncomfortable reality is that “stored” does not automatically mean “retrievable,” and retrievable does not guarantee recoverability when systems are under stress. This gap is where many Web3 applications quietly fail, even if the underlying storage looks solid on paper.

What’s missing from most conversations is the idea of a recovery window.

In traditional systems, recovery expectations are implicit. If something breaks, teams know roughly how long it will take to restore access. In decentralized environments, that clarity often disappears. Data might still exist on the network, but access becomes inconsistent. Latency spikes. Some nodes drop out. Other nodes respond slowly or not at all. From a user’s perspective, the app is simply broken — regardless of how decentralized the storage layer claims to be.

This is why the distinction between stored, retrievable, and recoverable data matters. Stored data merely exists somewhere. Retrievable data can be accessed consistently under normal conditions. Recoverable data, however, can be restored within a known time frame after disruption. Most Web3 storage narratives stop at the first definition. Real applications require the third.

When recovery is uncertain, teams start making compromises. They add fallback gateways, private caches, or centralized mirrors to protect user experience. These decisions are rarely advertised, but they are common. Not because builders don’t care about decentralization, but because reliability always wins over ideology when users are involved.

This is how Web3 apps quietly re-centralize. The storage layer remains decentralized in theory, while recovery and availability are handled elsewhere. The root cause is simple: recovery was never treated as a first-class design constraint.

A more honest way to think about storage is to ask a harder question: when something goes wrong, how predictable is the path back to normal operation? A system that cannot answer that question forces builders to invent their own safety nets. A system that can answer it reduces the need for those workarounds.

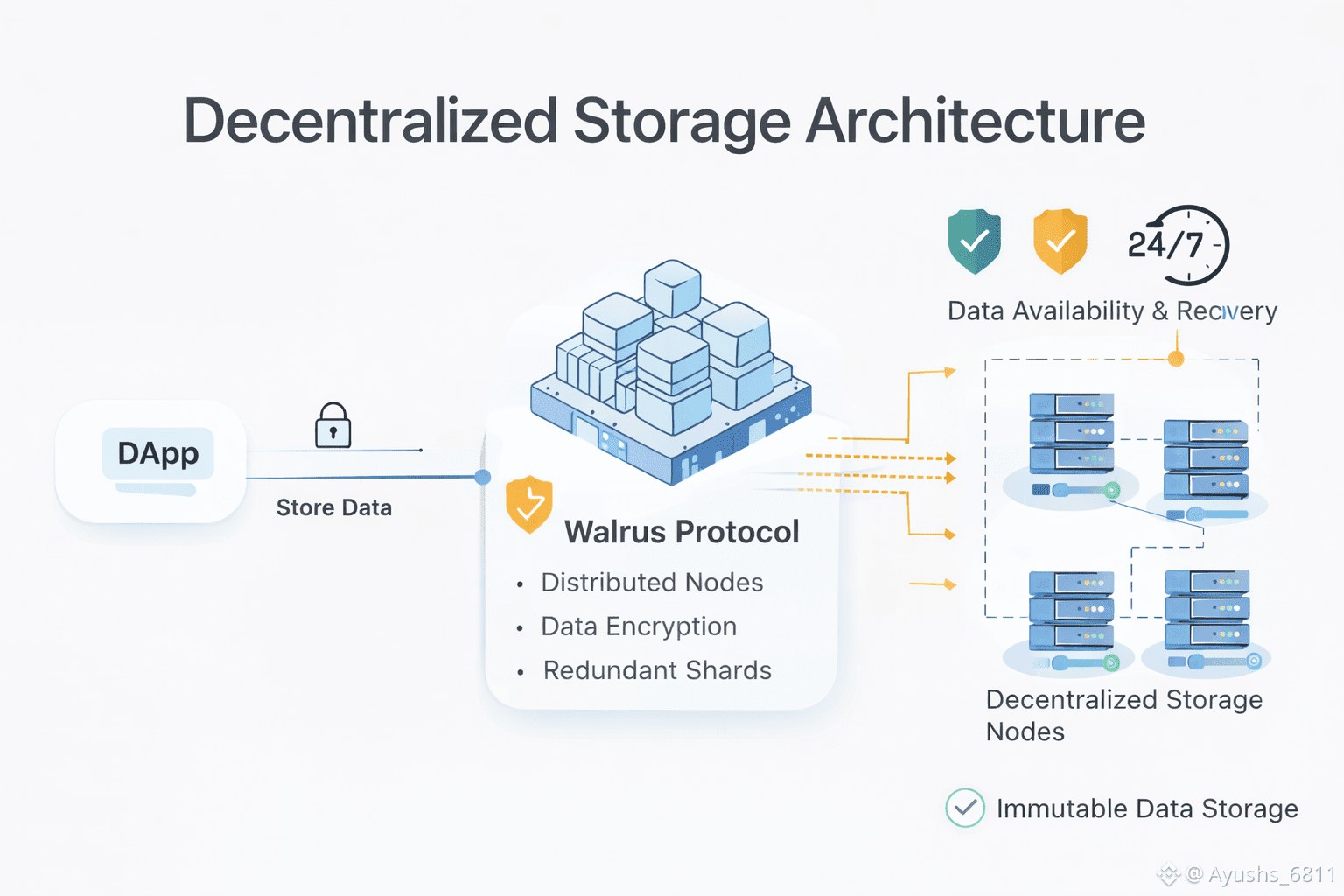

This is where the framing around Walrus becomes interesting. Instead of viewing it purely as “decentralized storage,” it makes more sense to evaluate it through the lens of availability and recovery guarantees. The value isn’t just that data is distributed, but that retrieval and recovery are treated as engineering outcomes rather than assumptions.

For builders, this shift in thinking matters more than any marketing claim. Applications don’t fail because data disappears entirely. They fail because access becomes unreliable at scale, or because recovery takes too long to be acceptable. Designing around recovery windows — not just storage existence — is what separates experimental systems from production-ready infrastructure.

My takeaway is simple: the next generation of Web3 apps won’t be limited by how cheaply they can store data. They’ll be limited by how confidently they can recover it when conditions are imperfect. In that context, recovery certainty becomes the real product, and storage is just the mechanism.

That’s why conversations around Walrus make the most sense when they focus on predictability, availability, and recovery — not as buzzwords, but as requirements for building applications that can survive real-world usage.