Distributed systems fail in three predictable ways.

Nodes lie.

Nodes leave.

Nodes vanish.

Most protocols pretend one of these will not happen.

Walrus assumes all three happen constantly — and designs storage around that assumption.

This is not paranoia.

This is realism.

The Problem Is Not Failure — It’s Partial Failure

When a server dies cleanly, systems recover easily.

When a node behaves maliciously, systems can detect it.

The real enemy lives in the middle:

Nodes that respond sometimes

Nodes that send correct data once, incorrect data later

Nodes that disappear mid-epoch

Nodes that reappear without memory

Walrus treats partial failure as the default state of the network.

That single assumption reshapes everything.

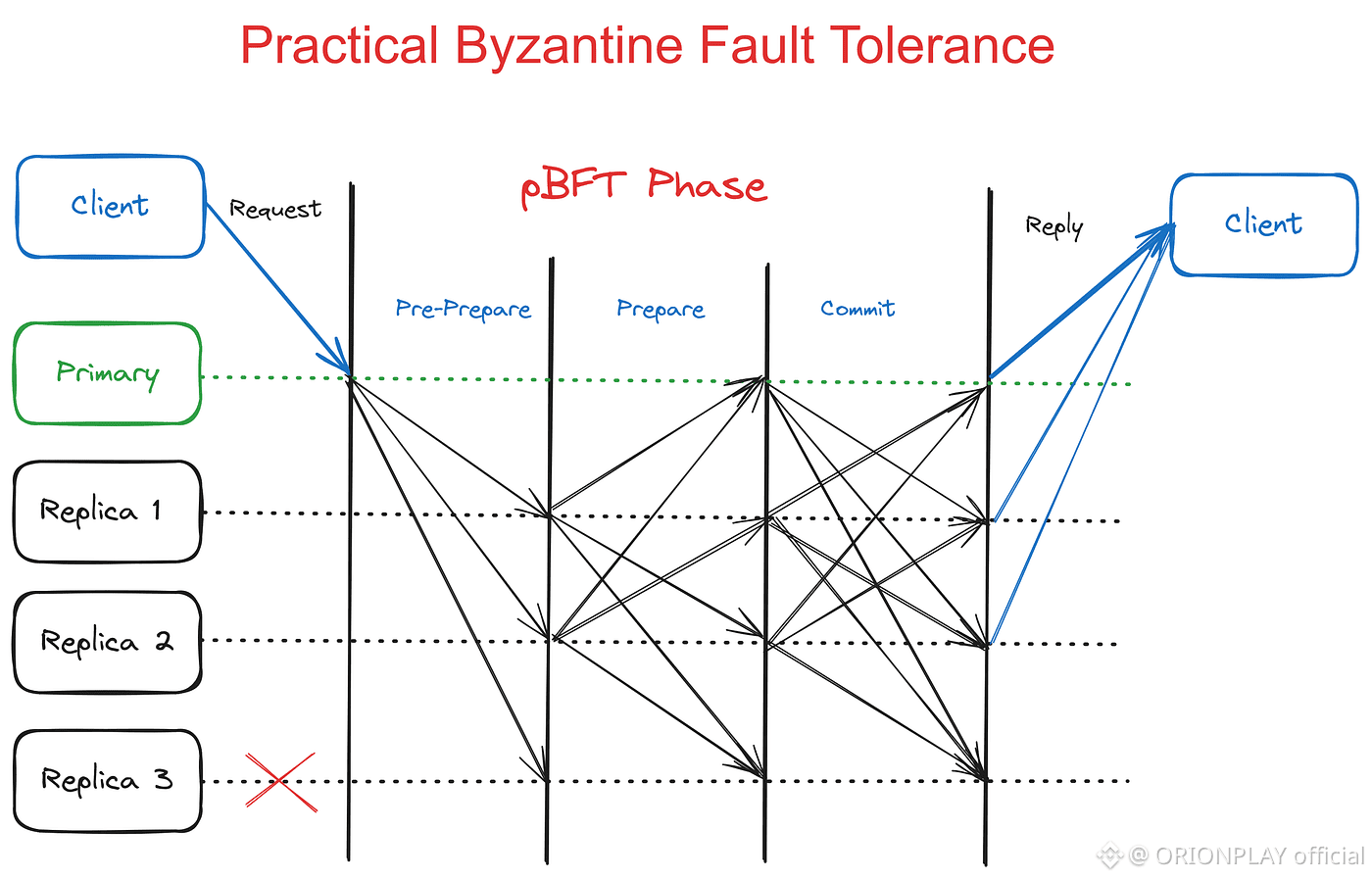

Byzantine Behavior Is Not an Edge Case

Byzantine faults are not theoretical villains.

They are:

Disk corruption

Network partitions

Software bugs

Misconfigured operators

Incentive-misaligned actors

Walrus does not ask whether nodes are honest.

It asks:

“What fraction can be dishonest without killing memory?”

The answer it builds around is strict, mathematical, and unforgiving.

3f + 1: The Quiet Backbone of Survival

Walrus operates under a simple but powerful rule:

For every 3f + 1 storage shards,

At most f can be faulty,

And the system still survives.

This is not optimism.

This is a boundary.

Everything — encoding, recovery, staking, committees — is shaped to ensure this threshold is never crossed.

Memory does not depend on trust.

It depends on quorum geometry.

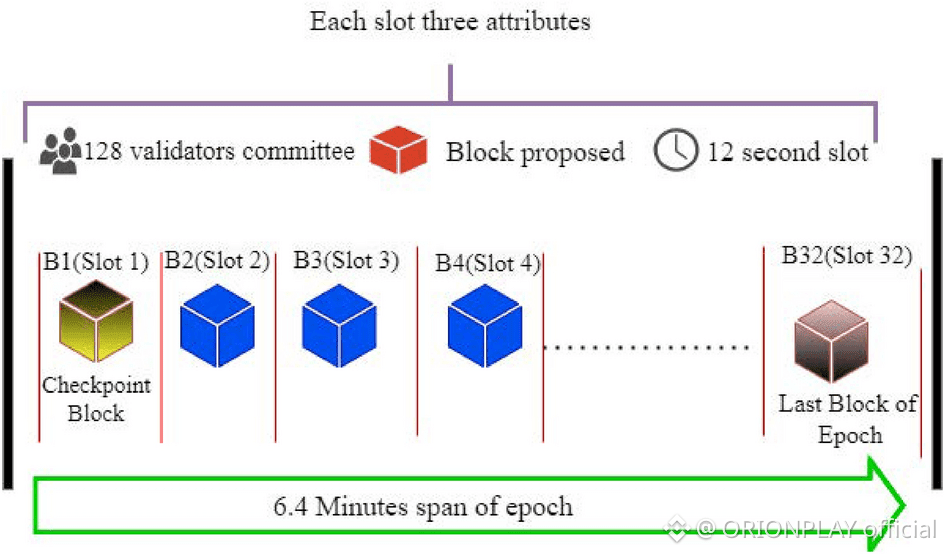

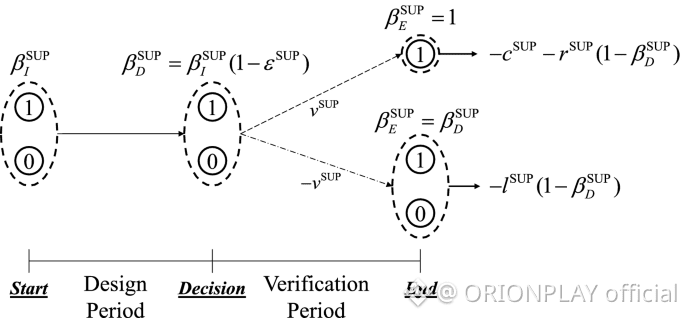

Epochs: Why Walrus Refuses to Assume Stability

In Walrus, time is segmented.

Each segment is an epoch.

Why?

Because nodes are not permanent.

Hardware fails.

Operators quit.

Stake moves.

Economics shift.

Instead of resisting change, Walrus contains it.

During each epoch:

A committee is fixed

Storage responsibility is clear

Proofs are evaluated

Rewards and penalties accrue

At epoch boundaries:

Responsibility migrates

Memory transfers without rewriting

Slivers recover themselves

Availability remains continuous

Change becomes routine instead of catastrophic.

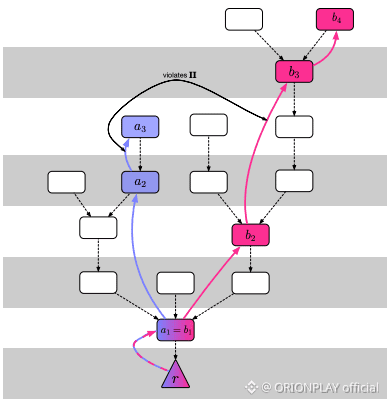

When Writers Misbehave

A malicious writer can:

Upload inconsistent slivers

Attempt to poison reconstruction

Try to trick nodes into storing garbage

Walrus responds coldly.

Every reader:

Reconstructs data independently

Re-encodes it

Recomputes commitments

Verifies consistency against on-chain facts

If inconsistency exists, all honest readers reject the blob identically.

No forked realities.

No “some users see it, some don’t.”

Truth is binary.

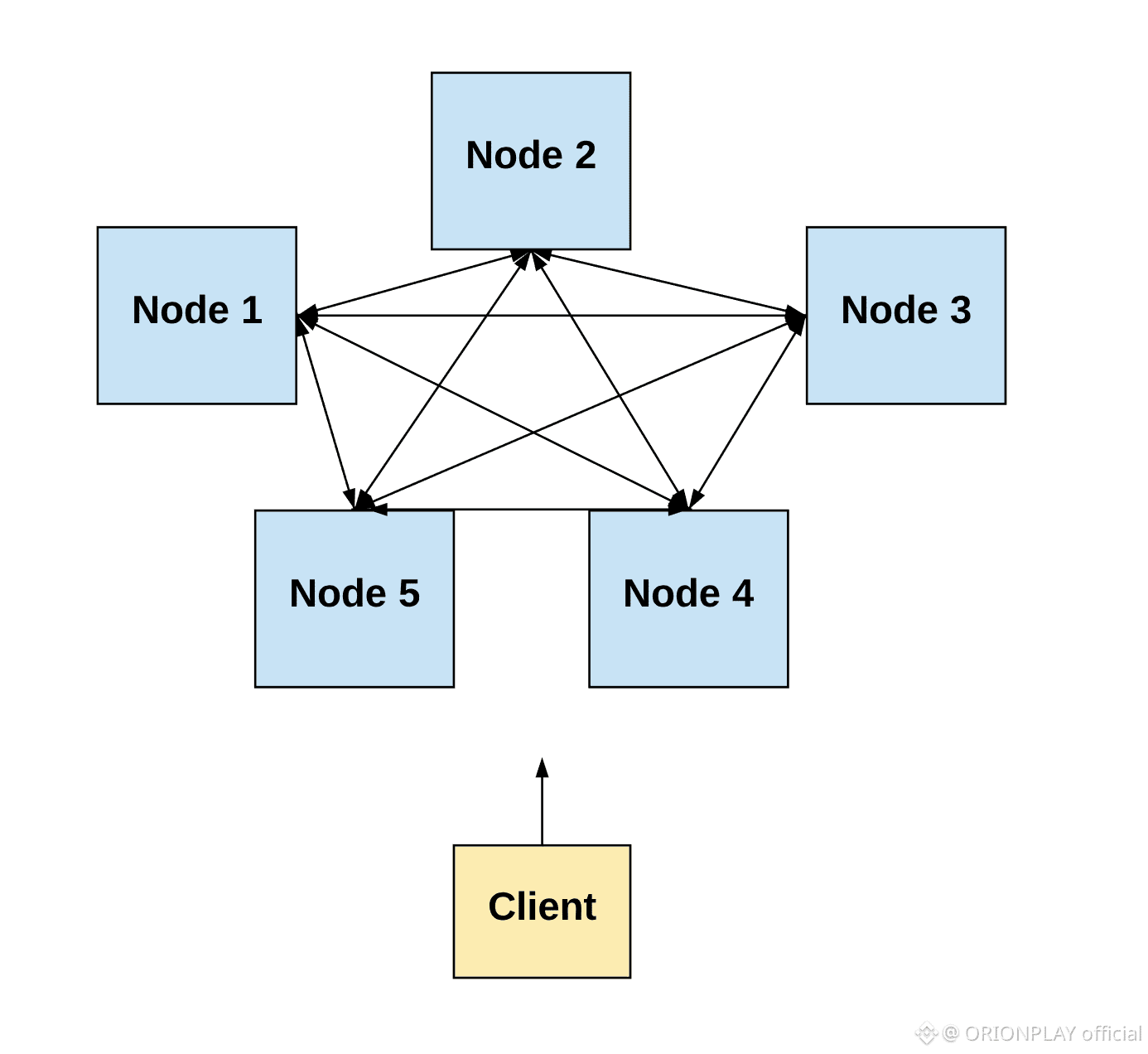

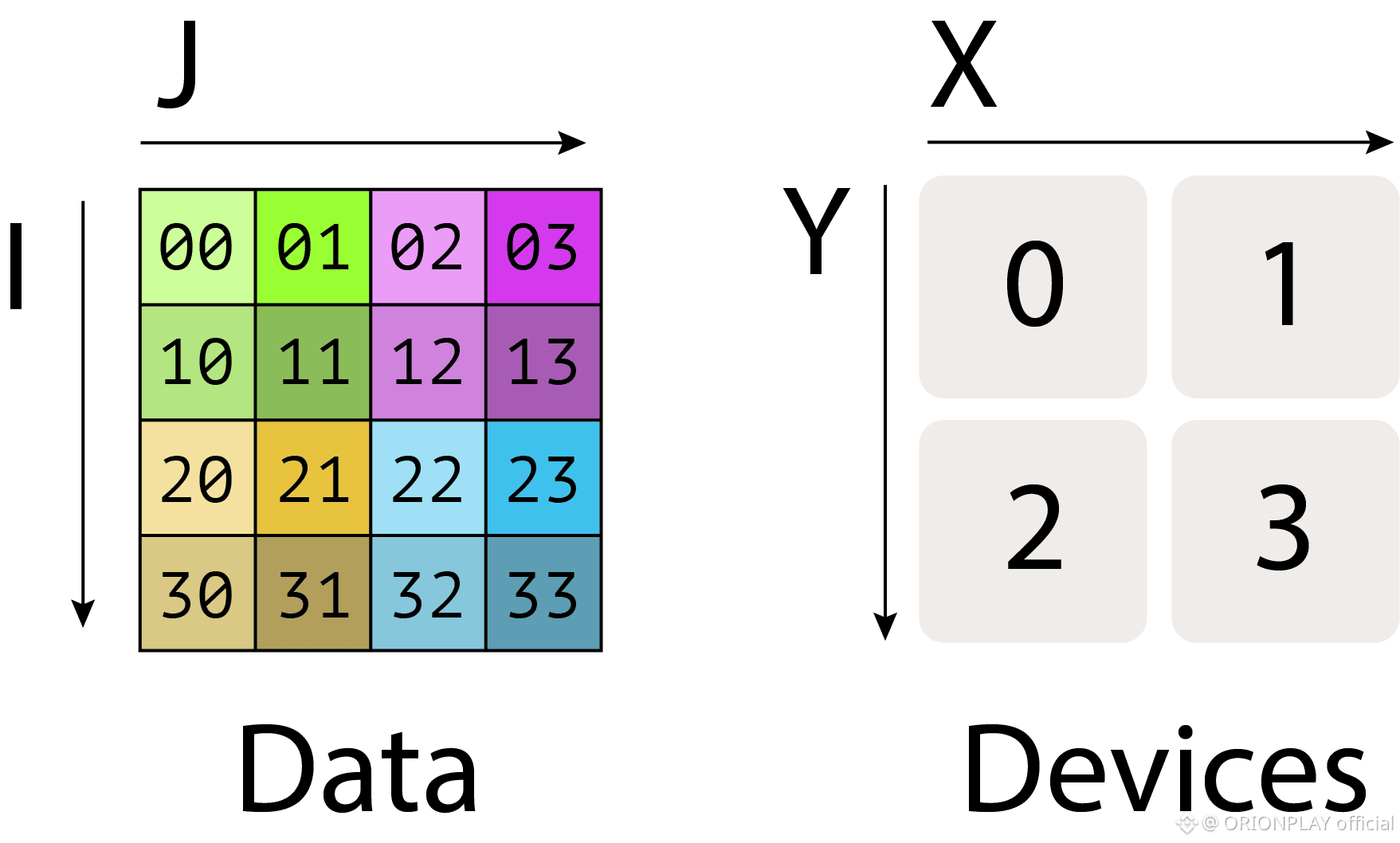

Slivers: Memory in Fragments, Not Copies

Walrus does not store files.

It stores slivers.

Each node holds:

A primary sliver

A secondary sliver

Commitments proving correctness

No node holds the whole truth.

But enough nodes together always can.

This prevents:

Data monopolies

Targeted censorship

Single-point corruption

Cheap impersonation attacks

Memory is distributed by design — not as an afterthought.

The Genius of Two-Dimensional Recovery

When a node misses its sliver:

It does not ask for the entire blob

It asks neighbors for intersections

It reconstructs only what it lost

Bandwidth scales with damage, not total data.

This matters more than it sounds.

In large networks:

Failures are constant

Full recovery would bankrupt the system

Incremental recovery keeps it alive

Walrus recovers like a living organism — not like a backup restore.

Reading Under Hostility

A Walrus reader:

Does not trust any single node

Does not assume synchrony

Does not require coordination

It requests slivers opportunistically.

It verifies each cryptographically.

It stops the moment reconstruction is guaranteed.

If nodes delay — it waits.

If nodes lie — it discards.

If nodes vanish — it routes around them.

Readers do not negotiate with the network.

They interrogate it.

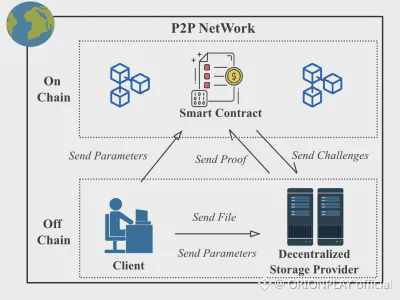

Storage Proofs That Don’t Suffocate the System

Most decentralized storage systems drown in their own audits.

Every file.

Every epoch.

Every node.

Walrus refuses that treadmill.

Instead:

Nodes store slivers for all blobs

Challenges target nodes, not files

Proof cost grows logarithmically

This changes the economics entirely.

Nodes cannot selectively forget.

They cannot optimize dishonesty.

They must remember — or pay.

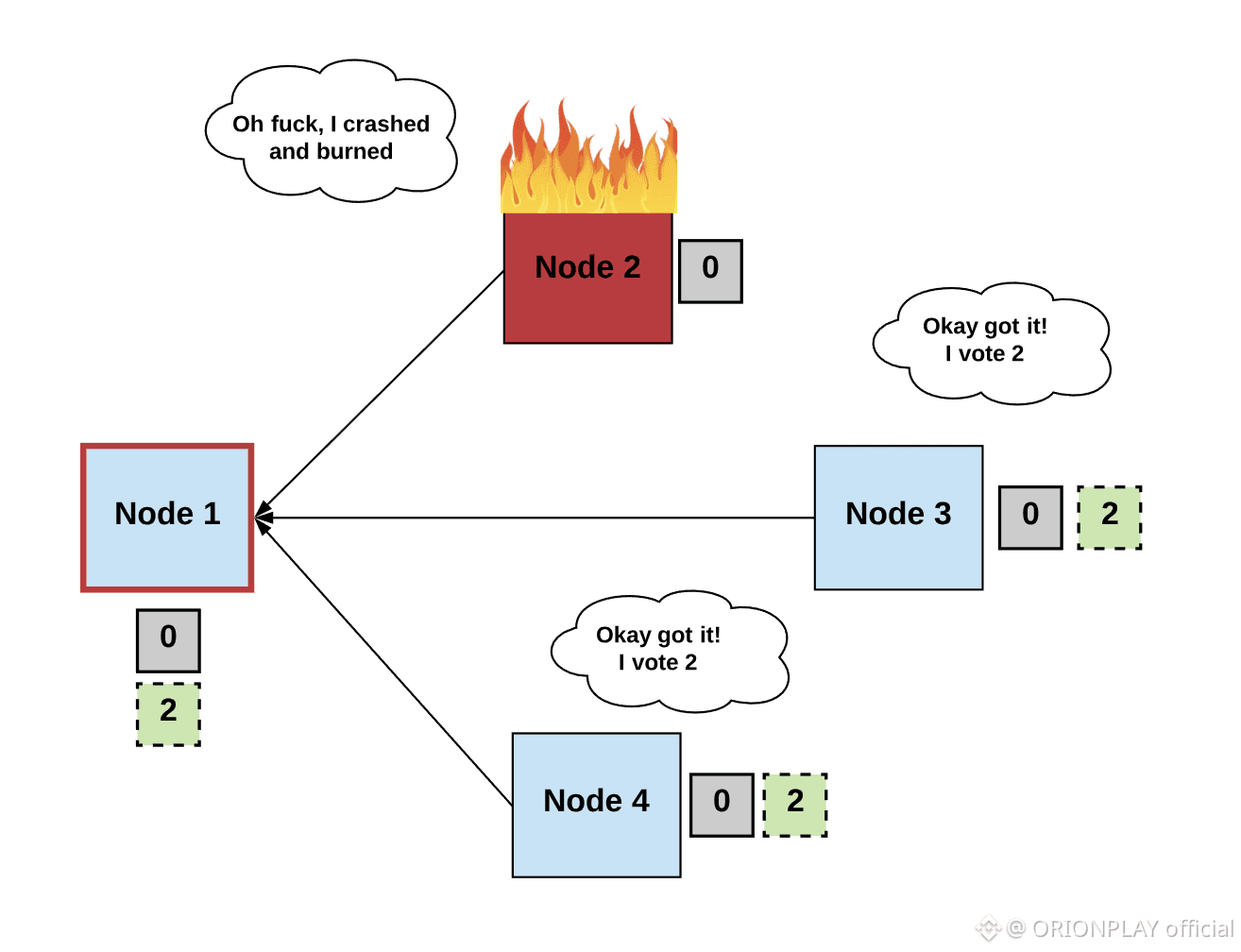

When Nodes Leave Without Saying Goodbye

Nodes churn.

Some exit gracefully.

Some disappear silently.

Some lose data unexpectedly.

Walrus treats all three the same:

Shards migrate

Recovery protocols activate

Stake absorbs the cost

There is no nostalgia for departed nodes.

Memory belongs to the network — not the machine.

Slashing Is Not Punishment — It’s Physics

In Walrus, slashing is not moral judgment.

It is conservation of system integrity.

If a node:

Loses shards

Fails challenges

Refuses migration

Disrupts recovery

Capital is burned or redistributed.

This does two things simultaneously:

Compensates honest participants

Makes future misbehavior irrational

Memory becomes the cheapest option.

Why Partial Reads Matter More Than Full Ones

Walrus optimizes for something subtle:

reading only what is needed.

Source symbols:

Appear twice

Exist on multiple nodes

Can be accessed without full decoding

This allows:

Faster reads

Lower latency

Lower compute cost

Smarter caching

Memory retrieval becomes surgical, not brute-force.

What Happens When Too Many Nodes Refuse?

Walrus does not pretend neutrality is absolute.

If more than f nodes deny serving a blob:

Availability is no longer guaranteed

The system converges on rejection

Memory is declared lost — transparently

There is no silent failure.

This honesty matters more than false promises.

The Deeper Pattern: Memory as a Process

Walrus does not treat data as static.

It treats memory as:

Encoded

Verified

Migrated

Challenged

Renewed

Truth is not stored once.

It is maintained continuously.

This is the philosophical shift most systems never make.

Final Thought 🧠

Walrus does not try to prevent failure.

It assumes failure is permanent — and still makes memory work.

Nodes will lie.

Nodes will leave.

Nodes will vanish.

And the data will still be there.