Tusky shutting down is the kind of event that exposes what decentralized storage really is. Not in theory, not in whitepapers, but in the only situation that matters: when the product layer disappears and users still need their data. People love to talk about storage like it’s a solved problem—cheap bytes, “permanent” claims, fancy architecture diagrams. But none of that is real until an app exits and the network either keeps the data usable or quietly turns “decentralized” into a technicality.

That’s why I see Tusky’s wind-down as a credibility exam for Walrus, not a negative headline. Walrus is supposed to be decentralized blob storage on Sui, paid via $WAL, built to handle the messy stuff: node churn, partial outages, and operational exits. If Walrus is actually infrastructure, this is when it proves it. If users struggle to retrieve, migrate, or re-publish their data, then the protocol may still be alive while the user experience is dead—and in the real world, that’s indistinguishable from failure.

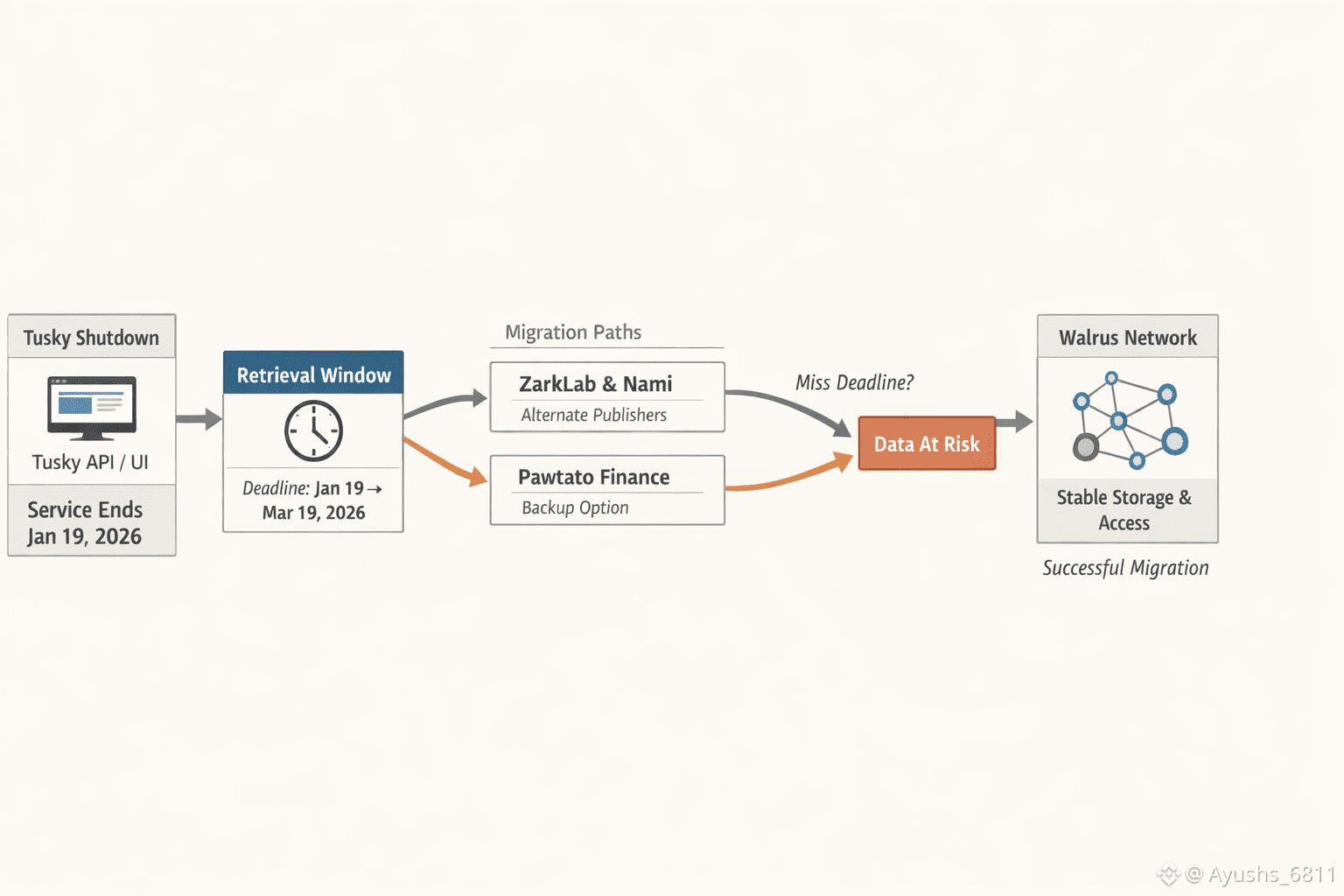

The uncomfortable truth is that most “decentralized storage” narratives hide behind one thing: the access layer. Users don’t live on the protocol. They live inside a UI, an API, an aggregator, a publisher. Tusky gave that convenience layer. When it sunsets, normal users don’t suddenly become protocol engineers. They need replacement paths that work without friction, and they need them before deadlines become cliffs. The protocol can be technically correct and socially irrelevant at the same time.

This is also where Walrus has a legitimate structural advantage, at least on paper. Walrus is designed around redundancy and recovery mechanics that assume nodes will come and go. Real networks are chaotic. Nodes drop. Connectivity degrades. Operators leave. If a storage network needs everything to stay online and coordinated, it’s fantasy. If it’s designed to tolerate partial loss and keep recovering, it has a chance in production. Walrus is selling that posture—resilience under churn—so a shutdown-driven migration wave is basically the highest-pressure test it could ask for.

But I’m not going to pretend this is automatically a win. There are two ways Walrus can still lose, even if the protocol itself is fine. The first is concentration. If most users depended on Tusky as the “front door,” and now they depend on one replacement publisher as the new front door, decentralization hasn’t improved. You just swapped the gatekeeper. The second is throughput and reliability during a spike. Migrations aren’t smooth, evenly distributed events. They happen in bursts. Everyone panics at the same time, and the network is forced to perform under load. If retrieval fails, if re-publishing is confusing, if latency spikes, users won’t care about the elegance of the architecture. They’ll remember that storage wasn’t there when it mattered.

So I think the real question isn’t “can Walrus store data.” That’s too easy, and honestly it’s the wrong question. The real question is whether Walrus can keep data usable when the product layer disappears. Usable means I can find it, retrieve it reliably, move it, and re-anchor it through another provider without needing tribal knowledge. That is where decentralized storage projects either graduate into real infrastructure or get exposed as protocol-only experiments that never solved distribution.

The cleanest way to think about this is as a stress-test with three failure modes. The first is node volatility during peak migration. If a meaningful percentage of storage nodes churn while thousands of users are trying to pull and push data, weak systems degrade fast. Walrus should theoretically be more tolerant here, but theory only matters if repair capacity and network incentives keep pace with the load. The second is the end of the familiar endpoints. When the comfortable UX goes away, procrastinators show up late and discover that “decentralized” doesn’t help them if they don’t have a simple alternative. If Walrus wants legitimacy, the migration path has to be idiot-proof. The third is what happens after the fire drill. A shutdown can create temporary demand, but that’s not adoption, that’s emergency behavior. The real signal is whether users stay on Walrus after the migration wave passes, and whether the ecosystem ends up with many healthy publishers or just one new monopoly.

This is also why I’m allergic to the usual marketing comparisons. The only comparison that matters is operational. Walrus is trying to be active blob storage that survives churn and keeps recovery workable, but its biggest risk is still the access layer. Arweave’s narrative is permanence, which is powerful for archival use, but it’s not the same game as app-scale blobs that need active retrieval under volatility. Filecoin has a massive ecosystem, but anyone who has tried to explain Filecoin retrieval to normal users knows how quickly “decentralized” becomes “too complicated to bother.” Different tools, different trade-offs. A shutdown stress-test is really about how those trade-offs feel when users are in a hurry and the product layer is no longer protecting them from complexity.

If Walrus and the Sui ecosystem handle this well, it will be one of the rare moments where “decentralized storage” becomes believable to people outside the protocol bubble. If users can migrate cleanly, retrieve reliably, and continue using the network afterward, this whole episode becomes validation rather than damage. If, instead, the narrative becomes “you had to act before a deadline or you were stuck,” or “the app went away and access got messy,” then the market will quietly downgrade Walrus from infrastructure to experiment.

For me, the thing to watch isn’t the headline. It’s the outcomes. Do users report smooth migration or repeated retrieval failures? Does the ecosystem create multiple strong publishers, or does it funnel everyone into one replacement bottleneck? And once the shutdown window passes, does usage remain, or does it evaporate the moment the emergency is over? That’s the line between a protocol people respect and a protocol people ignore.