When people talk about Web3, they often talk about freedom, ownership, and decentralization as ideas. These words carry weight, but they are also easy to repeat without asking what they truly require in practice. If you spend time reading the blog published by Walrus Protocol, a very different picture begins to form. Walrus is not trying to persuade readers with ideology or excitement. It is not trying to make decentralization feel heroic or rebellious. Instead, it treats decentralization as a practical problem, one that shows up quietly when systems age, attention fades, and assumptions break. The blog reads less like a manifesto and more like a set of hard-earned lessons about what actually fails over time.

When people talk about Web3, they often talk about freedom, ownership, and decentralization as ideas. These words carry weight, but they are also easy to repeat without asking what they truly require in practice. If you spend time reading the blog published by Walrus Protocol, a very different picture begins to form. Walrus is not trying to persuade readers with ideology or excitement. It is not trying to make decentralization feel heroic or rebellious. Instead, it treats decentralization as a practical problem, one that shows up quietly when systems age, attention fades, and assumptions break. The blog reads less like a manifesto and more like a set of hard-earned lessons about what actually fails over time.

One thing becomes clear very quickly. Walrus is obsessed with durability. Not performance benchmarks for today, not shiny demos for this year, but the uncomfortable question of whether data will still exist and still matter years from now. Most blockchain systems are very good at proving that something happened. They can show that a transaction was signed, that a block was confirmed, and that a state change was valid at a certain moment in time. What they are much worse at is preserving everything around that action. Context, large files, history, meaning, and relationships between data pieces often live somewhere else. And that somewhere else is usually centralized.

The Walrus blog keeps returning to this problem in different forms, almost like the authors are circling the same wound from multiple angles. NFTs may live on-chain, but their images and metadata often do not. Decentralized identities may be anchored to a blockchain, but the records that give them meaning are stored elsewhere. AI systems may claim to be decentralized, but their datasets are fragile and often controlled by a few providers. When those providers change terms, shut down, or simply disappear, the decentralized system technically still exists, but functionally collapses.

Walrus does not describe this as a hypothetical risk. It treats it as something that has already happened many times and will continue to happen unless storage itself is redesigned. This is why the protocol does not present itself as a product you use once and move on from. It presents itself as infrastructure. Infrastructure is something you only notice when it fails, and Walrus is building for the moment when failure would otherwise be silent and irreversible.

A recurring idea in the blog is that cheap storage and reliable storage are not the same thing. Many systems focus on lowering costs by assuming that nodes will behave well, that incentives will always be attractive, and that networks will remain healthy. Walrus takes a more realistic view. Nodes fail. Operators lose interest. Markets shift. Attention moves elsewhere. Instead of hoping these things do not happen, Walrus designs around the assumption that they will.

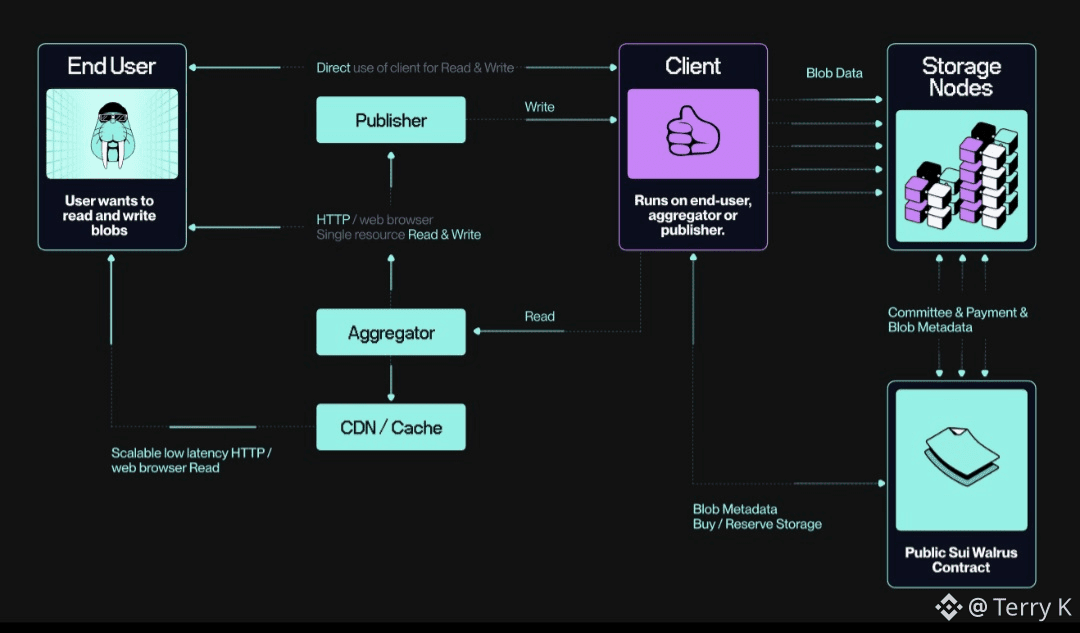

This is where the protocol’s approach to data availability becomes important. Rather than relying on full replication everywhere, Walrus uses an erasure-coded model that splits data into fragments and distributes them across many independent nodes. Only a portion of those fragments is needed to recover the original data. This design choice is not about elegance or novelty. It is about survival. It accepts that some pieces will be lost and plans for recovery instead of perfection.

The blog makes it clear that Walrus is not chasing perfect uptime in the present moment. It is chasing survivability across time. That is a very different goal, and it changes how you evaluate success. A system can be fast and cheap today but fragile tomorrow. Walrus seems willing to trade some short-term convenience for long-term resilience, even if that choice makes the protocol less exciting to talk about.

Another strong signal from the blog is how Walrus thinks about data itself. In many storage systems, data is passive. You upload it, retrieve it, and that is the end of the relationship. Walrus treats data as something more alive than that. It repeatedly refers to stored objects as programmable and verifiable. This means data is not just sitting somewhere waiting to be fetched. It can be referenced by applications, checked for integrity, and used as part of ongoing logic.

This way of thinking is important because it closes a gap that exists in much of Web3 today. Applications often rely on blockchains for logic and state changes, but fall back to traditional databases for anything complex or long-lived. Walrus is trying to remove that split. By making data objects first-class citizens that can interact with application logic, it allows developers to build systems that remain decentralized all the way down, without silently reintroducing centralized dependencies.

The blog often points out that many storage protocols stop at storing bytes. They do not care what those bytes represent or how they are used. Walrus does care. It wants stored data to be meaningful within an application’s workflow. This is why the protocol talks about supporting AI pipelines, identity systems, and media platforms. These use cases all depend on data that must remain accessible, verifiable, and interpretable long after the original application launch.

Access control is another area where the blog quietly challenges common assumptions. In much of Web3, openness is treated as an absolute good. Everything should be public, or else the system is considered compromised. Walrus does not accept this framing. It recognizes that real systems often need controlled visibility. Not all data should be visible to everyone, and not all users should have the same permissions.

The blog explains that Walrus handles access control at the protocol level rather than pushing it off-chain. This is a subtle but important choice. When permissions are enforced off-chain, decentralization becomes shallow. The data may be distributed, but control is not. By enforcing access rules within the protocol itself, Walrus allows data to remain decentralized while still respecting practical requirements around privacy and control.

This approach is not presented as secrecy for its own sake. It is presented as a condition for adoption. Enterprises, regulated platforms, and serious applications cannot function if all data is exposed by default. Walrus seems to understand that if decentralized storage is going to be used outside of experiments and demos, it must support selective access without breaking its own principles.

When the blog talks about the $WAL token, it does so in a noticeably restrained way. There is no language about price, speculation, or excitement. Instead, the token is described in terms of responsibility. WAL pays for storage. WAL rewards nodes that keep data available over time. WAL aligns incentives so that availability is maintained even when usage patterns change.

This framing is important because storage is not a one-time action. Uploading data is easy. Keeping it alive for years is hard. The blog repeatedly emphasizes that WAL exists to make this ongoing obligation sustainable. Nodes are not paid just for being present. They are paid for continuing to serve data reliably, even when that data is no longer popular or frequently accessed.

As more applications rely on Walrus for data they cannot afford to lose, the relevance of WAL grows naturally. Not because of narratives or trends, but because the protocol is doing work that needs to be done continuously. This ties economic value directly to usefulness, which is a quieter but stronger foundation than attention-driven models.

If you step back and look at the Walrus blog as a whole, it becomes clear that it is not trying to make decentralized storage sound exciting. In fact, it often assumes the opposite. Storage is boring when it works. It only becomes interesting when it fails. Walrus is building for that moment of failure, for the time when an application is no longer fashionable, when node operators are no longer motivated by hype, and when infrastructure either holds up or quietly collapses.

The tone of the writing suggests a team that is comfortable being early and uncelebrated. There is an acceptance that building durable systems is slower and less visible than launching flashy products. There is also an understanding that responsibility increases as adoption grows. Once applications depend on your data layer, mistakes are no longer theoretical. They affect real users and real outcomes.

Walrus is choosing a path that values consequences over promises. It is not trying to redefine the world overnight. It is trying to make sure that when the world changes, the data people depend on does not disappear with it. That is not a story that spreads quickly, but it is a story that matters deeply to anyone who has seen systems fail quietly in the background.

In the end, the Walrus blog reveals a project that is not chasing applause. It is chasing endurance. It is asking what happens after the excitement fades, after the headlines move on, and after only the infrastructure remains. By focusing on availability, programmability, and responsibility, Walrus is positioning itself as a data layer meant to last, not just to launch.

That quiet intention explains everything else. It explains the careful design choices, the restrained tone, and the focus on long-term incentives. Walrus is not trying to be remembered for being loud. It is trying to be remembered for still being there when everything else has changed.