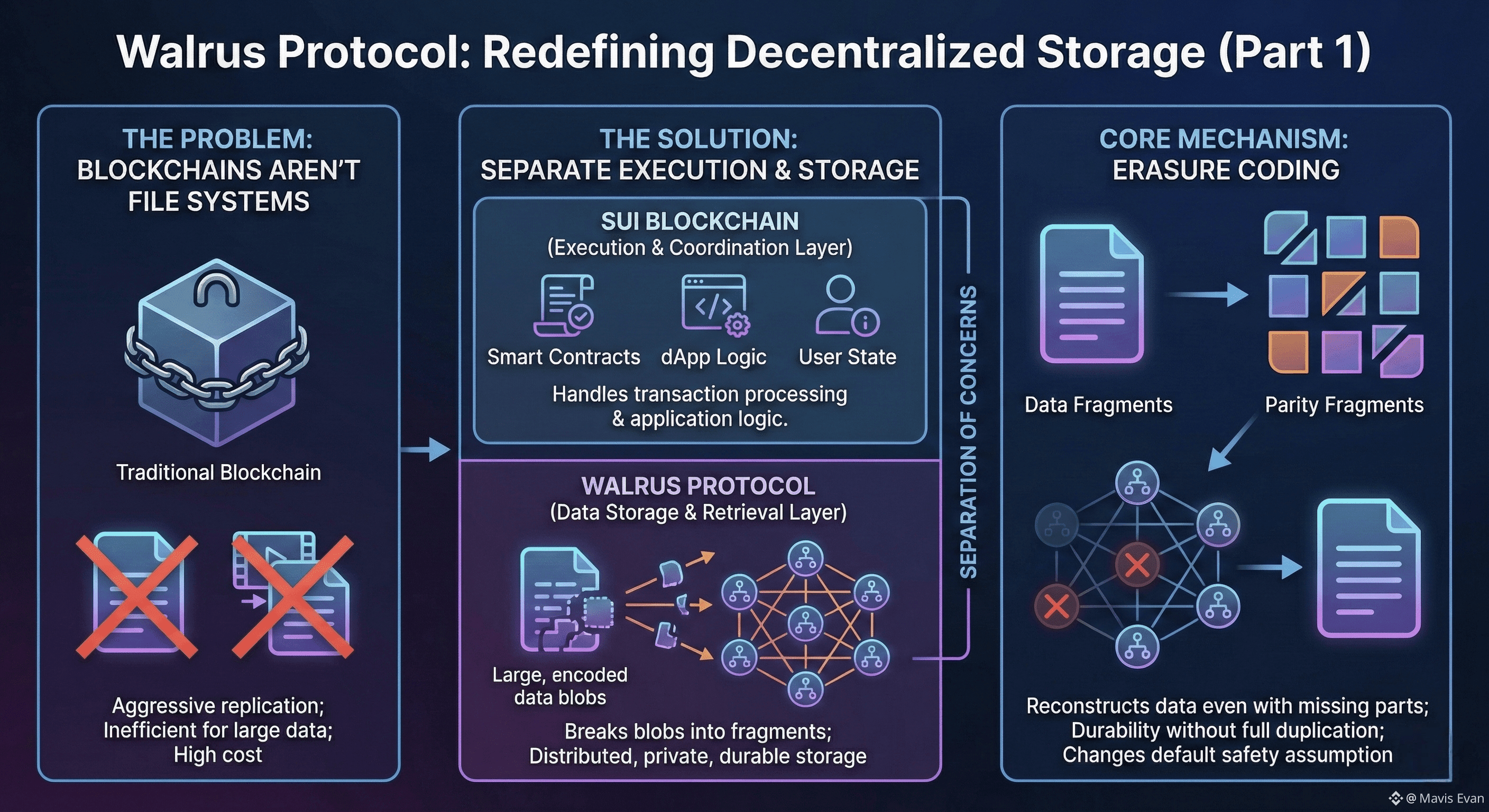

Decentralized systems have become very good at moving value, but they still struggle with something more basic: storing large amounts of data in a way that is private, durable, and economically rational. Blockchains were never designed to be file systems. They replicate state aggressively, which keeps networks honest but makes them painfully inefficient for anything beyond small records. Walrus exists to address that mismatch by separating the idea of data availability from the idea of global replication.

At a conceptual level, Walrus treats storage as its own problem rather than a side effect of transaction processing. Instead of asking every participant to hold full copies of files, it breaks large blobs into encoded fragments and distributes them across a decentralized network. The system relies on erasure coding so that the original file can be reconstructed even when parts of it are missing. This is not about squeezing costs through clever compression. It is about changing the default assumption that safety requires full duplication.

Running on the Sui blockchain shapes how this design is used. Sui provides the execution and coordination layer, while Walrus handles the heavy lifting of storing and retrieving data. For developers building decentralized applications, this means application logic and user state can live where they already expect, but large datasets are moved off the critical execution path. That separation is what makes the protocol practical for anything that involves real files rather than tiny metadata pointers.

The privacy component is not an add-on. Walrus supports private interactions at the protocol level, which matters because raw storage alone is not enough. Many decentralized applications fail the moment sensitive data is involved. If a user’s documents, training data, or transaction history must be hidden from the network while still remaining verifiable, the storage layer has to understand that requirement. By embedding privacy into how blobs are handled and retrieved, Walrus avoids the common trap of pushing confidentiality into application code.

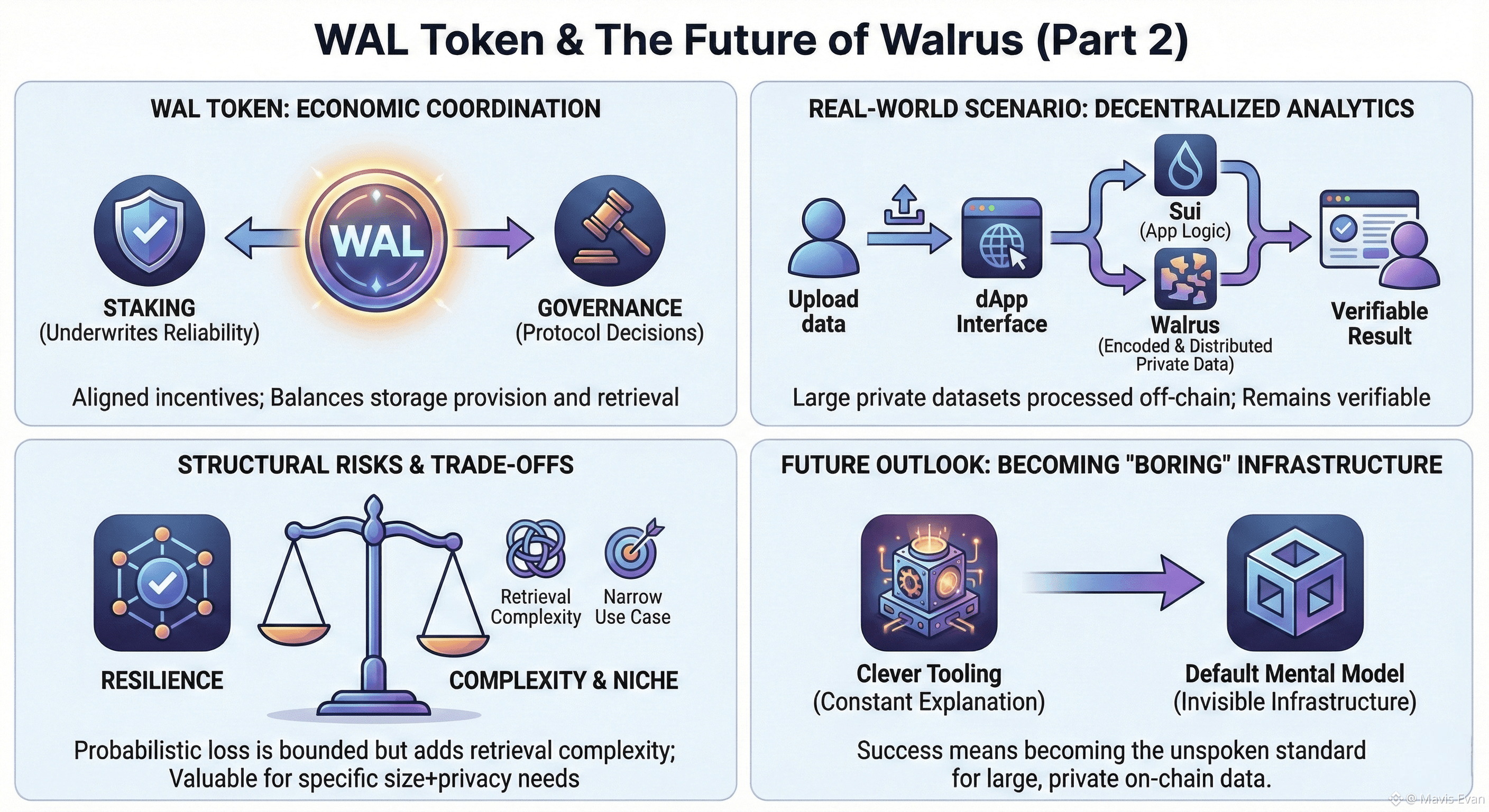

The WAL token sits at the center of this system because storage networks need more than bandwidth. They need aligned incentives. When users stake or participate in governance, they are not speculating on a generic asset. They are underwriting the reliability of the network. In practical terms, WAL becomes the coordination mechanism that balances who provides storage, who retrieves it, and how protocol decisions evolve. Without that economic layer, erasure coding is just mathematics with no reason to persist.

Consider a real scenario. A team building a decentralized analytics platform wants to store large private datasets that users upload for processing. Putting those files directly on-chain would be financially impossible. Using a centralized cloud would undermine the project’s core promise. With Walrus, the application runs on Sui, but the datasets are encoded into blobs and distributed across the Walrus network. Users interact through familiar dApp interfaces, while the data itself remains fragmented, private, and recoverable even if some storage nodes disappear.

This architecture also changes how developers think about failure. In traditional blockchains, losing data usually means losing the chain. In Walrus, loss is probabilistic and bounded. The system is designed with the expectation that some nodes will always be offline. The erasure coding scheme absorbs that instability so applications do not have to. That resilience is not free, though. It introduces complexity in retrieval paths and places heavy importance on correct encoding and decoding logic.

The structural risk is that Walrus sits in a narrow band of use cases. If developers only need small pieces of data, they will not adopt a specialized storage layer. If they need massive public archives, they may not care about privacy. Walrus is most valuable when applications need all three properties at once: size, confidentiality, and decentralization. That is a real but limited slice of the market.

Over time, this infrastructure will succeed or fail based on whether it becomes boring. Not in the sense of being ignored, but in the sense that teams stop thinking about how their data is stored at all. If Walrus becomes the default mental model for handling large private datasets on-chain, then the WAL token will represent a functioning economic backbone. If it remains a clever system that requires constant explanation, it will struggle to escape the category of interesting but optional tooling.