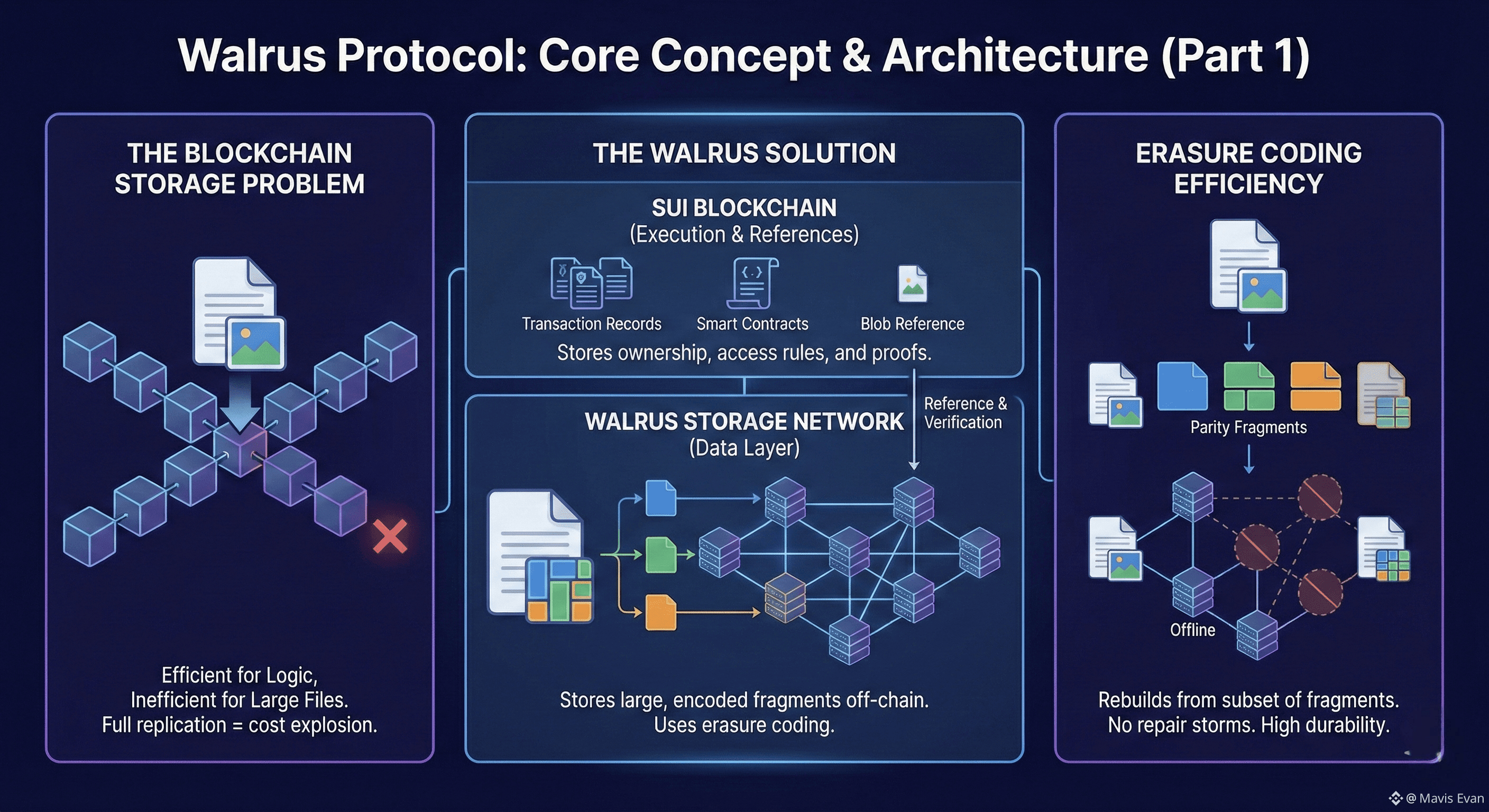

@Walrus 🦭/acc began as a response to a structural weakness that has followed blockchains since their creation. These networks are good at tracking ownership and executing small pieces of logic, yet they fail badly when asked to store large files. Every full node copies everything, which is manageable for transaction data but becomes impossible when users want to store images, documents, video, model weights, or application state that does not fit inside a few kilobytes. As decentralized finance has matured and non-financial use cases have grown, this mismatch has become more visible. Walrus exists to close that gap by building a storage layer that lives alongside the Sui blockchain rather than competing with it.

The timing of this project matters because crypto is leaving its early phase of speculative trading. New applications are trying to use chains as real infrastructure rather than as token casinos. Gaming studios need to store large media files. AI projects need to distribute training data. Enterprises need audit trails and backups that are not controlled by a single cloud provider. Traditional decentralized storage networks exist, but they are often loosely connected to the chains where assets and logic live. Walrus takes a different approach by integrating deeply with Sui so that data storage becomes a first-class on-chain concept.

The core idea behind Walrus is that not all data belongs on a blockchain, but ownership and access rules often do. The protocol separates data blobs from the transaction ledger. A blob can be any large binary object, from a PDF to a database snapshot. Instead of writing this blob to the chain, Walrus encodes it and spreads it across a network of storage providers. The blockchain only keeps the references and proof data needed to find and verify the blob later.

This design avoids the cost explosion that happens when hundreds of validators each store the same file. The erasure coding scheme used by Walrus breaks a blob into many fragments plus parity fragments. Only a subset of these fragments is required to rebuild the original file. If some nodes go offline or lose data, the file can still be recovered. More importantly, repairing a missing fragment does not require downloading the whole file. This removes the repair storm problem seen in older systems where every failure triggers heavy network traffic.

Running on top of Sui gives Walrus access to a fast execution environment and object-based state model. When a user uploads a blob, the transaction that creates its reference is processed like any other Sui object. Ownership, permissions, and expiration rules are recorded on the chain. This allows applications to treat data as a native asset type rather than as an off-chain afterthought.

Privacy is not limited to transaction data. Walrus supports private interactions around storage itself. The metadata stored on chain can be shielded, and access rights can be enforced through cryptographic proofs. This is essential for enterprise use cases where file names or access patterns may be as sensitive as the content itself. The system does not rely on trust in storage providers. It relies on verifiable proofs that data exists and remains retrievable.

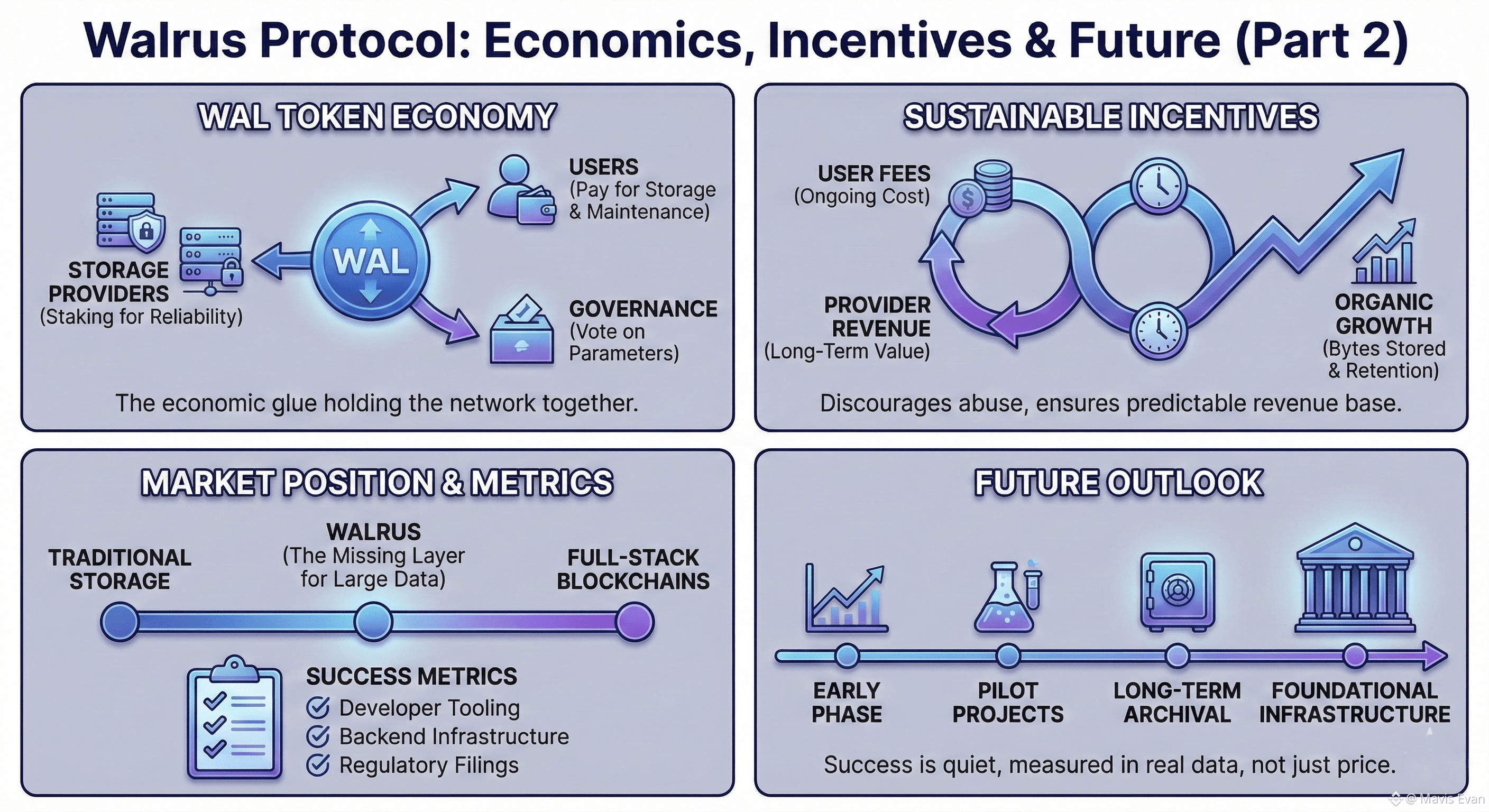

The WAL token is the economic glue that holds this network together. Storage providers stake WAL to signal reliability. Users pay WAL to upload and maintain blobs. Validators and verifiers earn WAL for checking proofs and maintaining the integrity of the reference layer. Governance rights are also tied to WAL, giving long-term participants a say in parameter changes such as pricing curves, minimum redundancy levels, and slashing rules.

Unlike simple payment tokens, WAL has a consumption pattern that mirrors physical storage economics. Fees are not one-off. Storing data over time creates an ongoing cost. This discourages abuse and forces users to consider the long-term value of what they store. It also gives the network a predictable revenue base that grows with usage rather than with speculation.

Because Walrus is new, on-chain metrics are still forming, but some patterns are already visible. The number of blob references on Sui tied to Walrus contracts has grown steadily rather than in spikes. This suggests that users are testing real workloads instead of chasing short-term incentives. Wallet growth follows a similar curve, with gradual adoption by developers rather than sudden retail inflows.

Transaction size on Walrus-related calls is larger than standard token transfers, reflecting the creation and management of blob references. Fee dynamics show that users are willing to pay higher costs for these operations because the alternative is storing data on centralized servers or bloated on-chain systems. Validator participation is stable, indicating that the computational burden of proof verification is not yet a bottleneck.

The presence of Walrus changes how liquidity forms on Sui. Instead of focusing only on trading pairs, capital begins to flow toward infrastructure. Projects that depend on large data sets no longer need to build their own storage layer or rely on third-party APIs. This lowers the barrier to entry for builders who want to deploy complex applications that include both assets and content.

For investors, the value proposition shifts from volume chasing to usage tracking. A storage-based protocol does not benefit from wash trading or empty liquidity pools. Its health is measured in bytes stored, retrieval frequency, and retention duration. WAL holders are indirectly exposed to the growth of decentralized storage demand rather than to market sentiment alone.

There are limits to this model. Storage is a competitive market with thin margins. Centralized providers achieve scale efficiencies that decentralized systems struggle to match. Walrus counters this by offering censorship resistance and cryptographic guarantees, but these features matter only to users who actually need them. Many applications will continue to choose cheaper centralized options unless regulatory pressure or trust failures push them away.

Another risk lies in the complexity of erasure coding at scale. While the protocol avoids full reconstruction storms, it still relies on a healthy distribution of fragments across the network. If too many providers fail at once or collude, availability could degrade. Designing slashing and incentive rules that prevent such scenarios without over-penalizing honest operators is an ongoing challenge.

The integration with Sui is both a strength and a dependency. Walrus benefits from Sui’s performance and object model, but it is also tied to its roadmap and adoption. If Sui fails to attract sustained developer interest, Walrus inherits that weakness. Conversely, if Sui grows rapidly, Walrus may face scaling pressure sooner than expected.

From a market perspective, Walrus positions itself between traditional decentralized storage networks and full-stack blockchains. It does not aim to replace either. It provides a missing layer that treats large data as something more than an afterthought. This makes it attractive for a class of applications that have been difficult to decentralize until now.

Looking ahead, the key metric will be how much real data lives on Walrus after the novelty wears off. Pilot projects are easy. Long-term archival and enterprise integration are harder. The protocol’s design suggests that it can handle this load, but proof will come only through sustained usage.

If current trends hold, Walrus will not become a household name among retail traders. Its success will be quieter, reflected in developer tooling, backend infrastructure choices, and regulatory filings rather than in social media metrics. In an industry that often measures progress in token price alone, a storage protocol forces a different conversation. It asks whether blockchains are ready to store more than numbers.