@Walrus 🦭/acc Protocol begins from a quiet observation that most market participants never bother to articulate data is treated as a liability long before it becomes a resource. In almost every cycle I have lived through, infrastructure projects promise scale, promise resilience, promise lower costs, and then quietly pass those costs back to users through complexity, forced liquidity events, or invisible operational risk. Walrus exists because that pattern kept repeating, and because the damage from it compounds slowly enough that few notice until it’s already too late.

When I first dug into the architecture, the conversations weren’t about throughput numbers or headline fees. They were about wasted capital. About systems that over-replicate information not because it’s efficient, but because it’s easy to reason about. About protocols that quietly push bandwidth costs onto operators until validators behave like short-term traders, dumping tokens simply to stay solvent. We’ve normalized this behavior in DeFi. Walrus does not.

What struck me is that this design does not chase ideological purity. It accepts an uncomfortable truth: data availability is not computation, and pretending otherwise has created a decade of technical debt. Most chains still force every participant to shoulder data they will never use, and then act surprised when participation centralizes. The result is familiar thin margins, fragile validator sets, and governance forums full of people arguing about symptoms instead of causes.

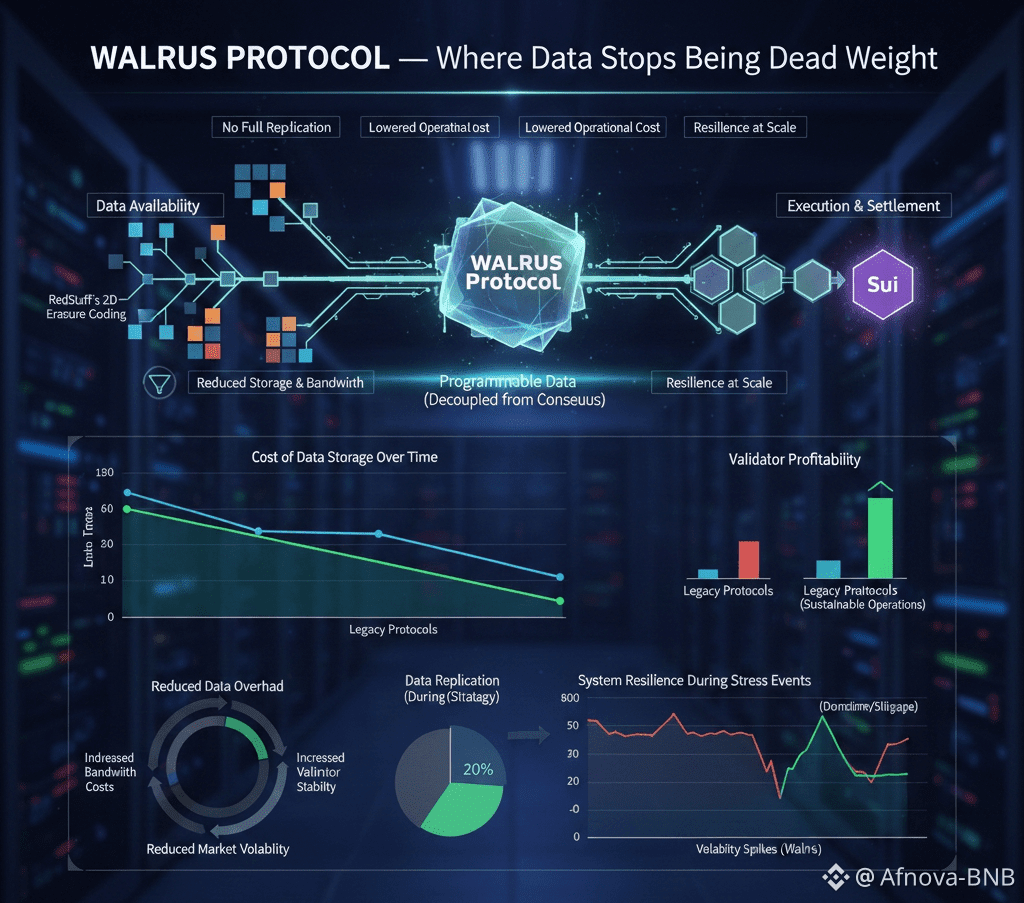

The core technical choice here RedStuff’s two-dimensional erasure coding is less interesting for what it is than for what it refuses to do. It refuses full replication as a default. It refuses to assume that redundancy must be brute-forced. This matters because storage overhead is not an abstract metric; it is a hidden tax that leaks into token economics, incentive design, and ultimately price behavior. When operators bleed quietly, they hedge loudly. Forced selling doesn’t come from fear alone it comes from bad system design.

I remember a discussion with another researcher last year, both of us frustrated by how often “decentralized storage” ends up meaning “centralized exit pressure.” His point was simple: if your infrastructure demands constant liquidity to survive, you’ve already built a reflexive risk loop. Walrus feels like a response to that exact critique. By lowering both storage and bandwidth requirements, it reduces the need for participants to constantly extract value just to remain operational. That changes behavior more than any incentive tweak ever could.

The relationship with Sui is often framed as a partnership, but in practice it looks more like a boundary being drawn correctly for once. Execution and settlement live where they belong. Data lives where it can breathe. This separation matters in ways that whitepapers rarely spell out. When data becomes programmable without being entangled in consensus, entire classes of hidden risk simply disappear. Upgrades become less traumatic. Failures become more localized. Governance debates shrink in scope instead of expanding endlessly.

This is where most growth plans fall apart. On paper, everything scales. In real markets, systems get stressed at the edges during volatility spikes, NFT mint storms, AI-driven demand surges. That’s when capital inefficiency shows up as slippage, downtime, or emergency parameter changes. Walrus seems designed by people who have watched those moments unfold in real time and decided not to pretend they were anomalies.

The ecosystem signals tell a similar story. Seeing brands like Pudgy Penguins build atop this layer isn’t interesting because of name recognition. It’s interesting because consumer-facing projects are brutally sensitive to infrastructure failure. They don’t survive on narratives; they survive on things working quietly at scale. Likewise, integrations with venues such as Bluefin suggest a recognition that traders don’t care where data lives only that it’s available when markets turn fast and unforgiving.

There are still risks, and pretending otherwise would be dishonest. Complexity doesn’t vanish; it moves. Two-dimensional coding introduces new operational considerations. Dependency on a specific execution layer concentrates certain upgrade risks. And the path toward stable pricing for large data blobs will test whether cost predictability can survive real enterprise demand. These are not red flags. They are the kinds of problems that only appear once a system is taken seriously.

What I appreciate most is what this protocol does not try to be. It does not posture as a governance revolution. It does not promise that token holders will suddenly behave rationally. It simply removes a layer of structural inefficiency and lets the market breathe. In my experience, that is the only kind of infrastructure change that endures across cycles.

I have watched too many projects chase attention instead of resilience, mistaking short-term usage spikes for product-market fit. Walrus feels quieter than that. More patient. Built with the assumption that the next wave of adoption won’t look like the last one, and that AI-driven systems will punish brittle data layers far more harshly than humans ever did.

In the long run, this protocol matters not because it will dominate headlines, but because it addresses a problem most investors only notice after it has already cost them money. Data availability is destiny in decentralized systems. When it’s designed poorly, everything else becomes a workaround. When it’s designed honestly, it fades into the background exactly where critical infrastructure belongs.