The way a file is stored does not concern most of users. They care that it loads fast. They care whether the link works. Do they care that the content is identical today and tomorrow? Builders in Web3 understand this, but many have encountered a tough problem. Storing content in a decentralized manner can be slower and more complex than traditional web hosting. If the experience is not painful, users go.

Walrus seeks to close this distance. It is a decentralized storage protocol for arbitrary large data objects, such as files or pieces of files. A blob is merely something that is not tabled. like Walrus is for blobs. It also assists in proofs that a blob is saved and that it’s available for retrieval later. Walrus was designed to make data available in the presence of a subset of storage nodes going down, or misbehaving. This scenario is sometimes referred to as a Byzantine fault environment. Walrus makes use of the Sui for coordination, payment and availability attestations. The blob content stays off-chain. Sui or its validators only see metadata.

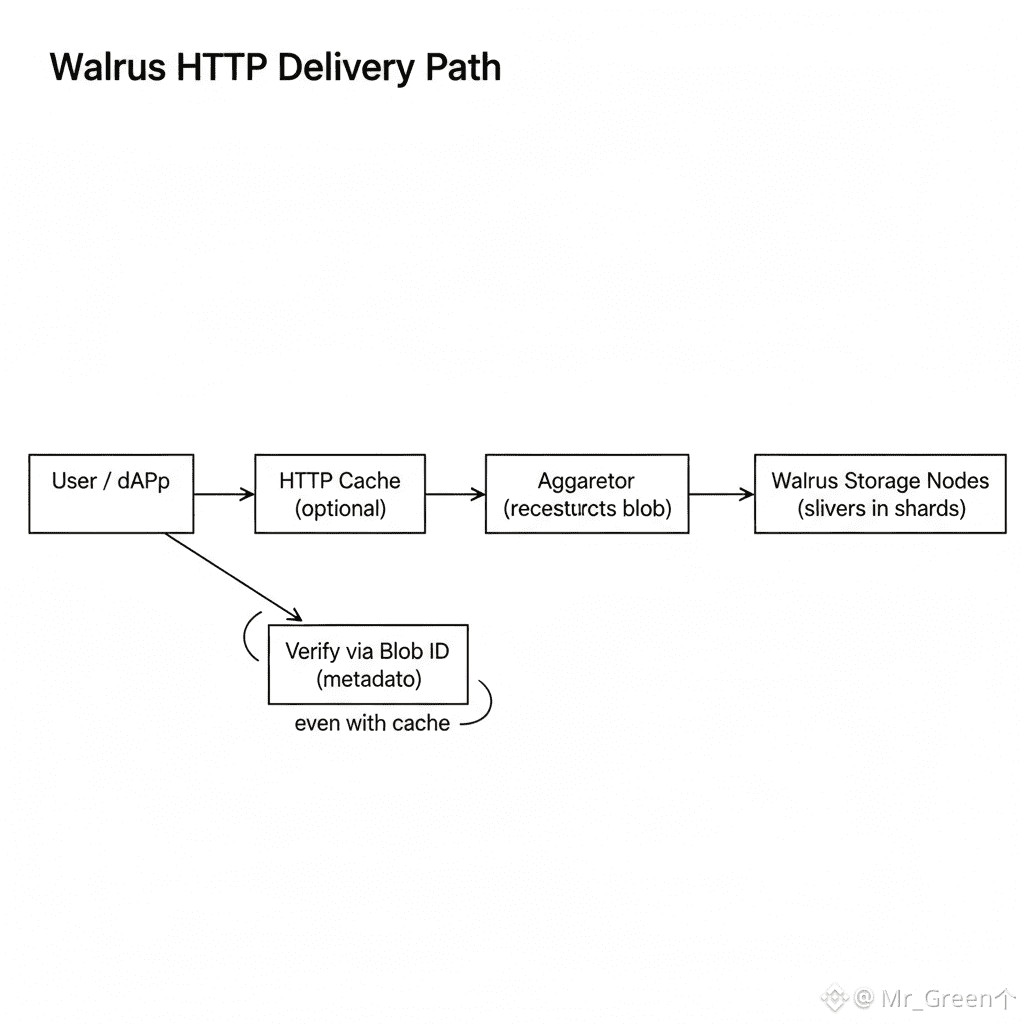

Here is the part that feels familiar to the web now. Walrus permits access via Web2 HTTP mechanisms. It does so with interfaces to aggregators and caches. These are not required. They are there to help making reads faster and easier.

An aggregator is a client that constructs the full blob from smaller persisted pieces. Walrus places chunks encoded portions of each blob on storage nodes. That’s not the kind of pieces a typical user wants to gather. They want the file. Heavy lifting is done by an aggregator. It asks the storage nodes for the necessary blocks. Then it reconstructs the blob. Then it presents the blob to users via HTTP.

This helps in a simple way. Instead it allows apps to use real web patterns. HTTP is the way a website requests content. A mobile app can do the same. A user can be up and running without having to learn new tools. Developers can leverage existing web libraries and caches. They can also take advantage of standard content delivery configurations.

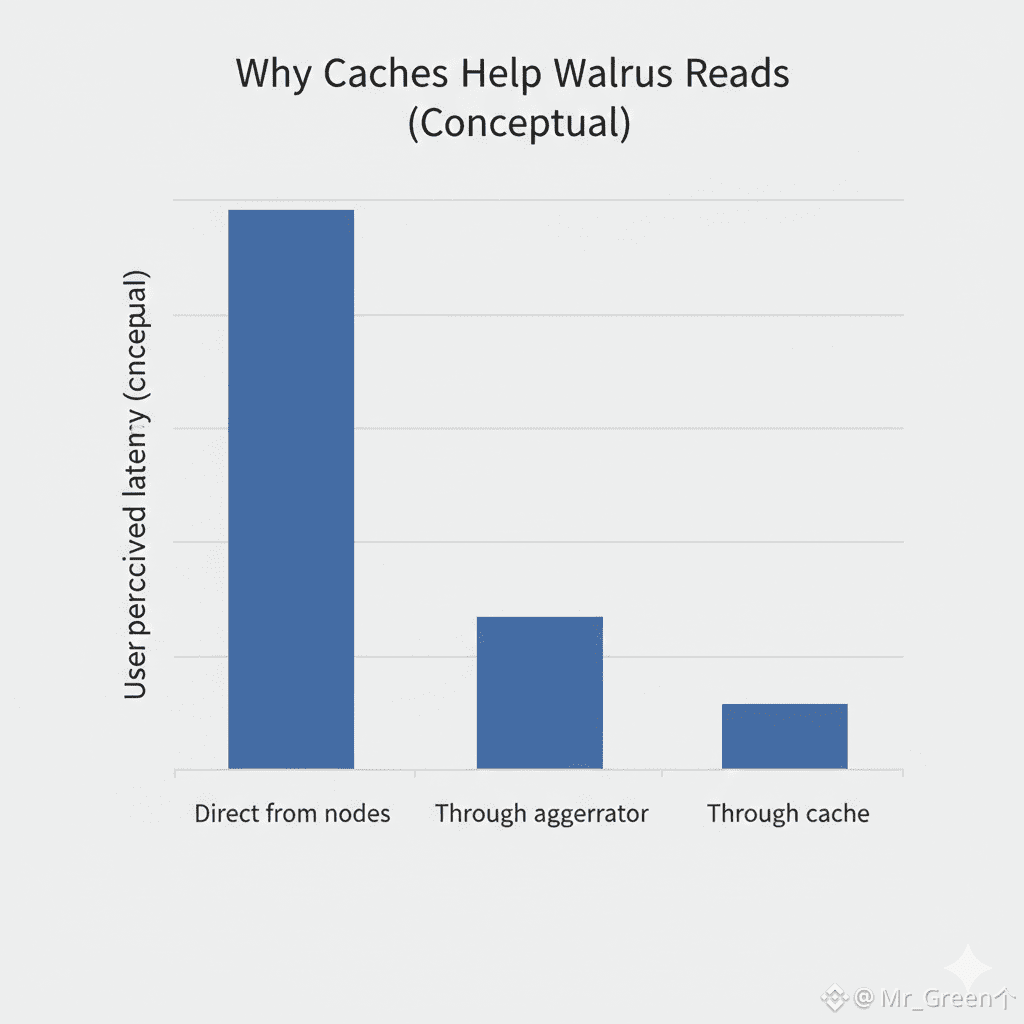

Walrus also supports caches. An on-disk aggregate with storage for popular results is called a cache. It caches blobs it has requested recently, so that they don’t need to be built every time. This offloads the storage nodes. It's reducing latency for users as well. It also shifts the cost of reconstruction across many requests.

One point that Walrus is crystal clear on. Aggregators and caches are optional. End users can continue to read directly from the storage nodes. Users are able to start a local aggregator as well. This is attractive to those who desire the most decentralization. It’s valuable, too, for teams that want total control.

Walrus also doesn't require you to make a blind leap of faith cache-wise. We design it with the fact that a client will be able to check the correctness. Walrus takes a blob id that ties the blob to its encoded entity and metadata. A client can verify that the data a cache returns matches what is committed by the blob ID. This is a key idea. Everything doesn’t have to have verification stripped from it for speed. Cache it could be fast, and the client can still verify.

This model is also consistent with how CDNs operate today. Walrus is not attempting to be a CDN. It tries to work well with CDNs. Caches can act like CDNs. They can reduce latency. They can improve connectivity. They can reduce repeated work. The approach of Walrus is to ensure that the actual content remains verifiable and accessible, even when the network partially collapses.

For developers, this is practical. You can put big media on Walrus. You can serve it over HTTP. You can continue to maintain a foundation that’s decentralized. You can also in times of need show availability. You can also maintain general user experience. That is often where the gap lies between a demo and a product.

This can be a big deal for DeFi and on-chain apps, too. DeFi frequently requires relatively large files that may not belong on-chain. These may be known as audit packs, evidence bundles and libraries. You probably want them to be accessible by anyone. You might also want them to load quickly on a dashboard. Caches can assist with HTTP delivery. The trust model can be kept clean by verifying through blob IDs.

Walrus is trying to meet users where they are. People already know HTTP. People already use browsers. People already rely on caching. Walrus keeps those habits. What it puts underneath them is a layer of decentralized storage. It also introduces a mechanism to validate what you are receiving. That is the quiet goal. Make Web3 storage feel usable, without ceding the power to validate the truth.