Enterprise storage has spent two decades perfecting a comforting story: put data in a small number of trusted places, wrap those places in identity controls and audits, and let the business move fast inside a predictable perimeter. That story is fraying in the moments that now define modern risk—cross-border teams working under conflicting regulations, software supply chains that pull in dozens of vendors, and AI pipelines that move terabytes of unstructured files through more tools than a security team can realistically map. Walrus is interesting because it doesn’t try to defend the castle harder. It changes the geometry of where data “lives,” turning large files into something closer to a swarm: broken apart, distributed, recoverable by math, and governed by explicit rules rather than silent vendor assumptions.

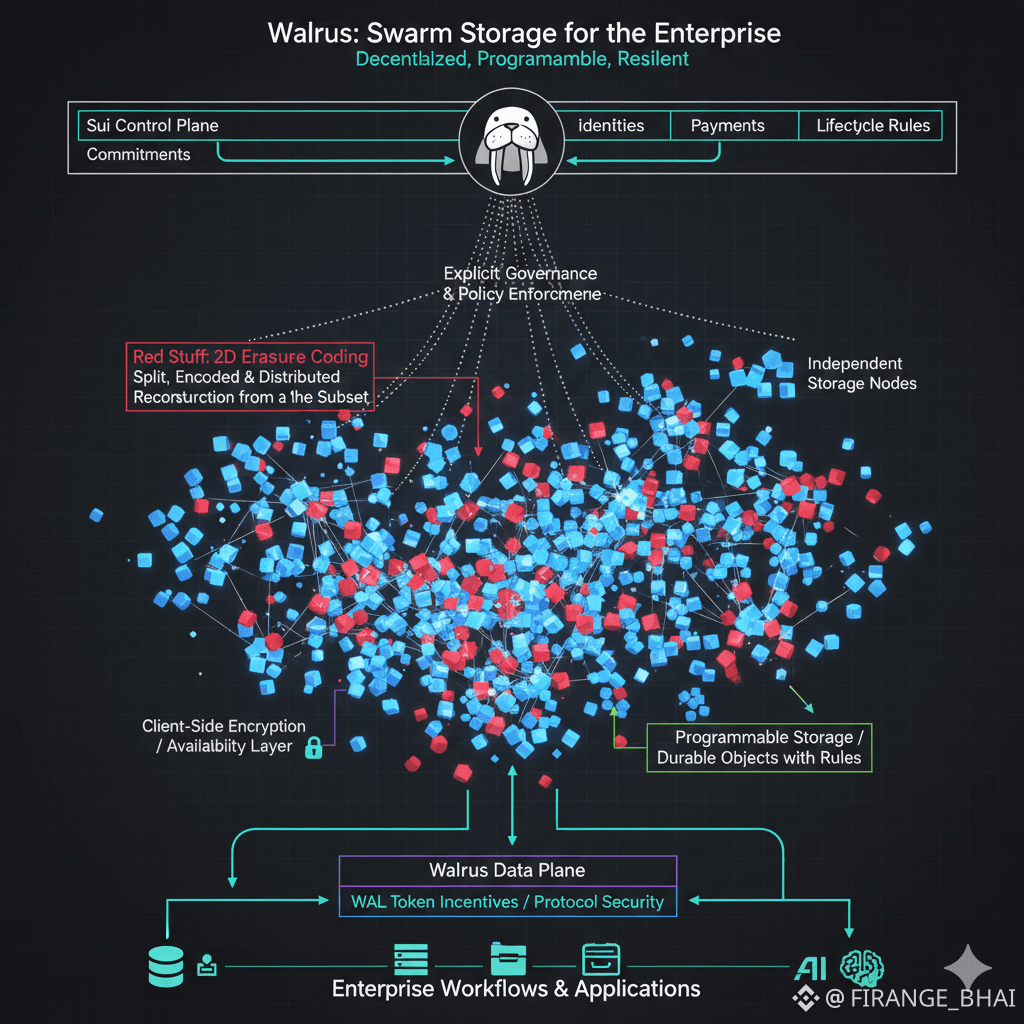

Walrus is a decentralized blob storage and data availability protocol integrated with the Sui ecosystem. The mental model that matters is the control-plane/data-plane split. Sui coordinates commitments, identities, payments, and lifecycle rules, while the heavy payloads live off-chain as large binary objects (“blobs”) stored across independent storage nodes. That division is not just an engineering convenience; it is a strategic decision that mirrors how enterprises already run infrastructure. In the enterprise world, the control plane is where governance lives: policies, permissions, audit trails, revocation, and accountability. Walrus keeps that layer anchored to an execution environment, while moving the bulk data to a network that can scale without pretending the blockchain should hold the bytes. The result is a system that behaves more like an infrastructure substrate than a crypto product: something you integrate into workflows, not something you “use” in a consumer sense.

The technical heart of that substrate is Red Stuff, Walrus’s two-dimensional erasure coding design. Traditional replication is blunt: copy the entire file several times and hope enough copies survive. Erasure coding is more surgical: split the file into symbols, add redundancy, distribute the encoded result, and reconstruct the original from a sufficient subset. Walrus pushes this further by treating recovery as a first-class constraint rather than an afterthought. If decentralized storage has a hidden Achilles’ heel, it’s not “can the file be recovered in theory,” but “can it be recovered quickly, predictably, and under adversarial churn without operational heroics.” Red Stuff exists to make recovery behave like an engineered process rather than a lucky outcome. The design is not about bragging that “two-thirds of nodes can fail.” It’s about keeping the bandwidth and coordination cost of recovery proportional to the data actually lost, so the network can heal itself without turning every failure into a system-wide scramble.

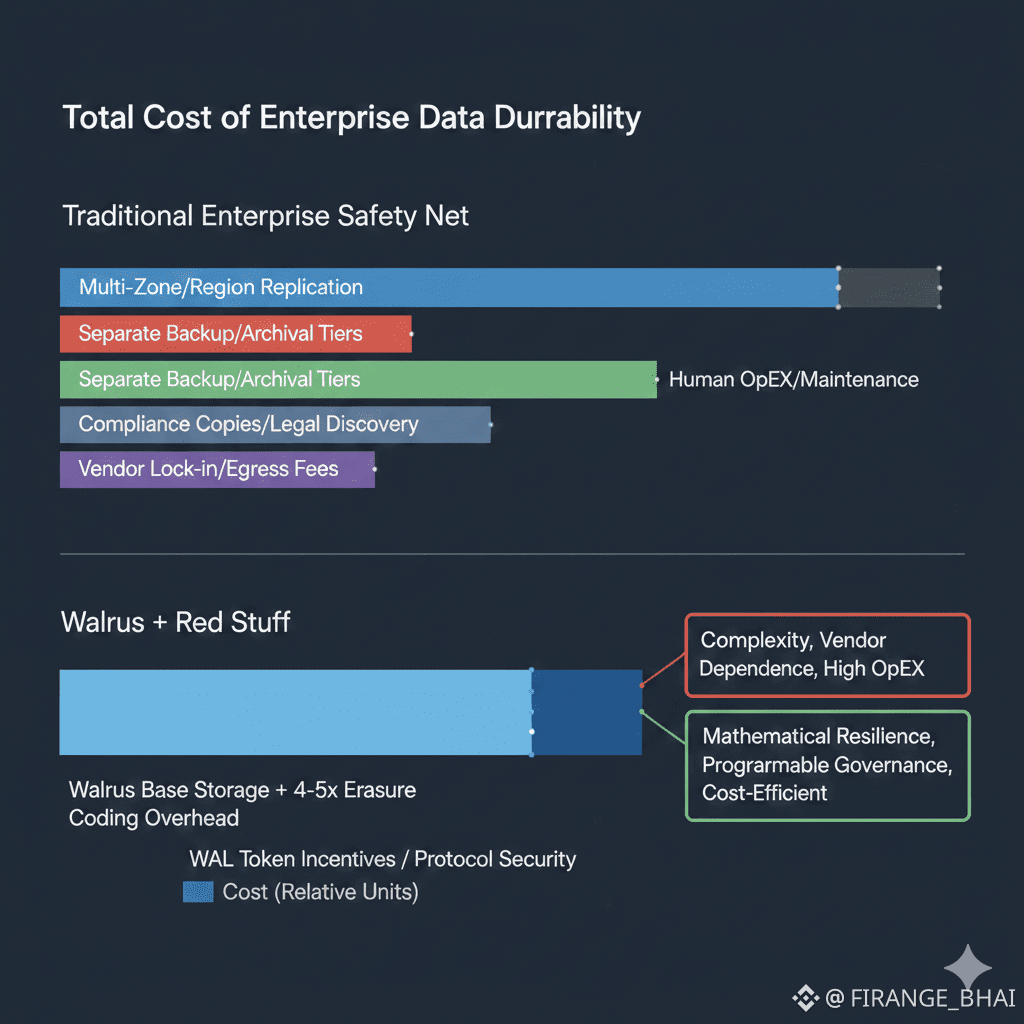

That recovery property is where Walrus becomes legible to enterprise architects. The common enterprise question isn’t “is this decentralized,” but “what happens at 3 a.m. when something breaks?” Walrus’s research claims that Red Stuff enables self-healing without centralized coordination, and that resilience can be achieved with an overhead on the order of a few multiples of the original data, rather than the much higher costs that come from simple replication. In practice, Walrus documents and related technical materials describe overhead around the four-to-five-times range for storing blobs with robustness, which is dramatic precisely because decentralized storage has historically paid for durability with brute force. Five times sounds expensive until you remember what enterprises already do when they take durability seriously: multi-zone replication, cross-region redundancy, separate backup tiers, separate archival vendors, and a growing maze of compliance copies. The real comparison is not “Walrus versus one S3 bucket.” The real comparison is “Walrus versus the total cost of the enterprise safety net,” including the cost of human work required to maintain it.

Walrus’s second quiet move is making storage programmable. That phrase is easy to dismiss because the industry has abused it, but here it means something concrete: stored blobs become objects with enforceable lifecycle logic, not passive bytes. When Walrus launched on public mainnet in late March 2025, it framed programmable storage as the ability to build custom logic around stored data while keeping the owner in control, including deletion, and allowing others to interact with the data without mutating the original. In enterprise language, that translates into a missing primitive: “durable data with rules.” Organizations almost never store data just to store it. They store it because it sits inside a workflow—retention schedules, revocation requirements, audit trails, cross-team access gates, evidence logs, and reconstruction of intent after incidents. Centralized storage systems bolt these rules on as software layers and trust the vendor substrate underneath. Walrus flips the order: the substrate itself is designed around rule-enforced persistence, so governance is not a separate product; it is the storage system’s default posture.

This is where Walrus’s privacy story becomes more credible than typical decentralization narratives. Decentralization doesn’t magically make data private; naïve replication can increase the number of machines that could leak it. Walrus approaches privacy as risk reshaping. First, fragmentation means no single storage operator holds a complete file, which changes the payoff curve for compromise. Second, client-side encryption keeps confidentiality with the key holder, turning the network into an availability layer rather than a confidentiality layer. This distinction matters to compliance teams because it separates “who can retrieve the data” from “who can read the data,” shrinking blast radius in a way that feels operationally real. It doesn’t eliminate legal questions about where fragments reside, but it can reduce the practical impact of any single failure mode. In a world where most breaches are caused by misconfiguration, credential theft, or insider access, reducing the value of any single compromised node is a meaningful step—not a philosophical one.

Incentives are where WAL enters, and this is where enterprise conversations often get uncomfortable. Tokens feel speculative, but they can also function as the native security budget of a permissionless infrastructure layer. WAL exists to align storage operators with availability obligations—staking, penalties, and governance decisions that shape protocol parameters. Markets are already assigning WAL meaningful value, with major trackers reporting a circulating supply around 1.577 billion tokens, a maximum supply of 5 billion, and market capitalization in the hundreds of millions of dollars, with recent prices hovering around the mid-teens in cents. This market layer cuts two ways for enterprises. On one hand, it introduces volatility and reputational baggage that traditional buyers dislike. On the other hand, it externalizes a cost that centralized vendors often hide: the cost of keeping the network honest and available. In a cloud contract, those costs are embedded in margin and enforced by legal agreements. In Walrus, they are embedded in stake and enforced by incentives and protocol rules. The governance question shifts from “will the vendor do the right thing” to “are the protocol incentives strong enough that doing the wrong thing is irrational.” That’s not automatically better, but it is auditable in a way centralized control rarely is.

The stakeholder map around Walrus is quieter than people expect because the real decision-makers are not always the loudest accounts. Mysten Labs matters because it built both Sui and Walrus and holds deep context on design trade-offs. Storage operators matter because they are the supply side of durability, and their unit economics will decide whether the network becomes resilient at scale or brittle under pressure. Developers matter because adoption is not a press release; it is a set of irreversible architecture decisions inside production systems. The most important “partners” in decentralized storage are rarely headline logos. They are the teams who quietly ship integrations, run nodes, pay bills, and build business logic that depends on the storage layer behaving correctly under stress. In enterprise infrastructure, credibility is earned when systems fail gracefully, not when they launch elegantly.

The trend most people miss is that decentralized storage is no longer competing mainly on “cheaper than S3.” It’s competing on exit costs and governance risk. Clouds are cheap until you count the price of leaving, the friction of cross-account migration, the tax of egress, and the existential risk of an account-level incident that halts operations. Walrus offers a different form of resilience: resilience against administrative lock-in and geopolitical pressure, not just disk failures. The contrarian insight is that the enterprise buyer who benefits most from decentralized storage isn’t necessarily the cost-sensitive one. It’s the risk-sensitive one—the organization that has already learned the hard way that concentration is an operational vulnerability. In that frame, Walrus is less “storage innovation” and more “risk diversification,” the same way multi-cloud strategies exist even when they’re inefficient, because the alternative is betting the business on a single governance regime.

AI makes this posture feel urgent rather than philosophical. Modern AI workloads generate and consume giant artifacts: training datasets, synthetic corpora, model checkpoints, embeddings, evaluation logs, and compliance evidence for how data was used. The hard problem is shared access with provenance, especially when datasets are curated across teams and vendors. Blob-first storage matches the shape of AI data because the objects are naturally large and versioned. Programmable storage hints at a future where access rules, retention constraints, and usage conditions are part of the data object’s lifecycle rather than brittle conventions enforced by a few overworked platform engineers. This matters because AI infrastructure failures are rarely “the file disappeared.” They’re “we can’t prove which dataset produced this model,” “we can’t reproduce training,” “we can’t revoke access cleanly,” or “we can’t validate integrity after the fact.” Walrus’s architecture is not a silver bullet, but it directly targets the mismatch between AI’s data appetite and enterprise governance expectations.

There are risks, and pretending otherwise is how infrastructure projects fail in the real world. Decentralized storage inherits chaos: node churn, heterogeneous performance, and network unpredictability can collide with enterprise expectations of deterministic latency and well-defined SLAs. Governance can centralize if staking concentrates, recreating a “few operators matter” dynamic under a different label. Regulatory obligations remain hard: data residency, deletion rights, and incident response do not become simpler because data is fragmented. Centralized hyperscalers retain a real advantage in tooling maturity—tiering, lifecycle management, legal discovery integrations, and contractual accountability backed by a single entity. The fairest counterargument is that hyperscalers already use erasure coding at enormous scale, with astonishing efficiency, inside controlled environments. Walrus should not be evaluated as “cloud replacement.” It should be evaluated as “trust model replacement” in the places where centralized control is itself the liability.

So the practical adoption path is hybrid by default. Enterprises can start with data that benefits most from vendor neutrality: audit archives, model artifacts shared across partners, public or semi-public datasets with integrity requirements, and cross-jurisdiction backups where administrative independence matters. Developers can use Walrus as a programmable data substrate where on-chain identities and off-chain blobs meet, while keeping hot transactional state in conventional databases and caches. The goal isn’t purity. The goal is reducing the number of existential dependencies hidden inside storage assumptions. A good Walrus integration doesn’t announce itself; it silently narrows the blast radius of failure modes that used to be catastrophic.

If Walrus succeeds, it will do so quietly. Success will look boring: rising utilization, stable operator participation, fast recovery under stress, and an expanding set of applications that treat a Walrus blob as a governed, persistent object rather than a temporary upload. WAL will remain volatile because markets are markets, but the signal to watch is not price; it’s whether the protocol keeps delivering the one promise enterprises actually pay for. When your data needs to outlive vendors, outages, and politics, you stop asking “where is it stored?” and start asking “what makes it recoverable?” Walrus is an attempt to make that answer mathematical, programmable, and harder to revoke by force.