It wasn't during a coin launch or protocol introduction that decentralized storage truly clicked with me. It happened when attempting to transfer a few gigabytes of material for a modest project, including photos, PDFs, and versioned datasets. Not a single "crypto native." Just the kind of chaotic data that all genuine products produce. At that point, the unsettling reality of most onchain narratives becomes apparent: while blockchains excel at settlement and ownership, they are appalling at storing the real content of the digital world.

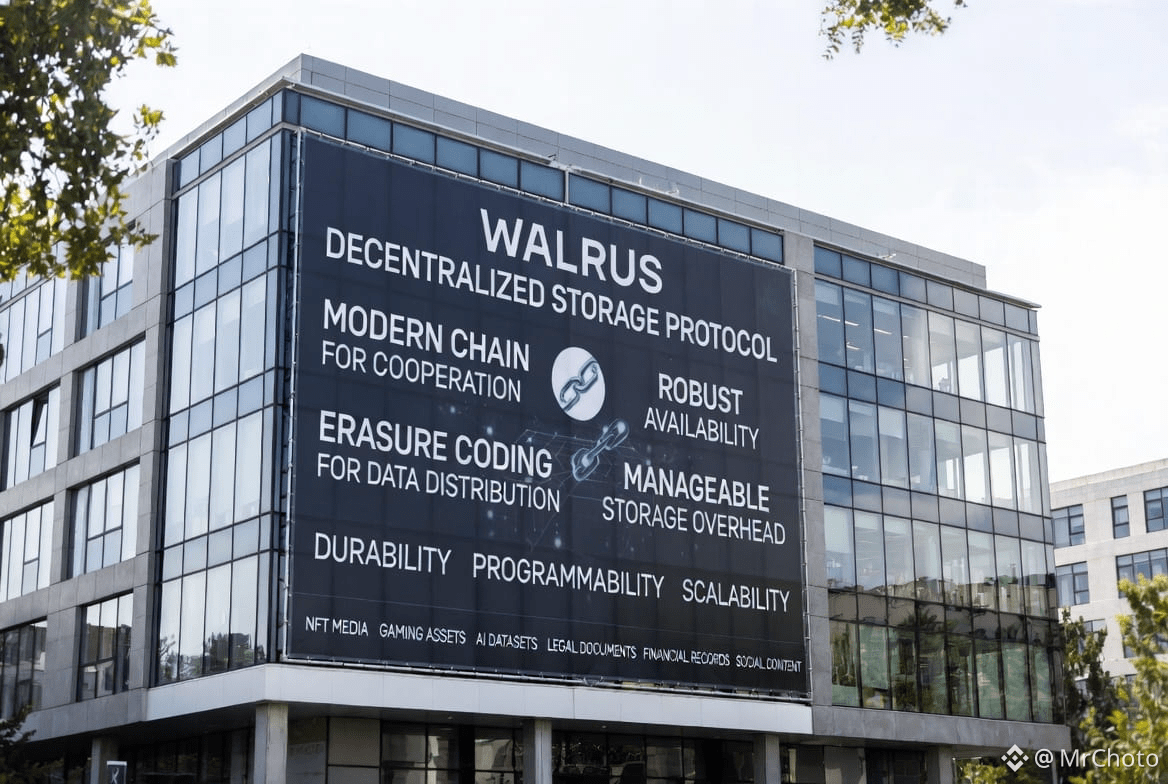

Because Walrus isn't promoting decentralized storage as an ethical substitute for AWS, that gap is where it becomes significant. It aims to make storage more durable, predictable, programmable, and scalable. It's the distinction between "storage as an idea" and storage on which a legitimate business may be built.

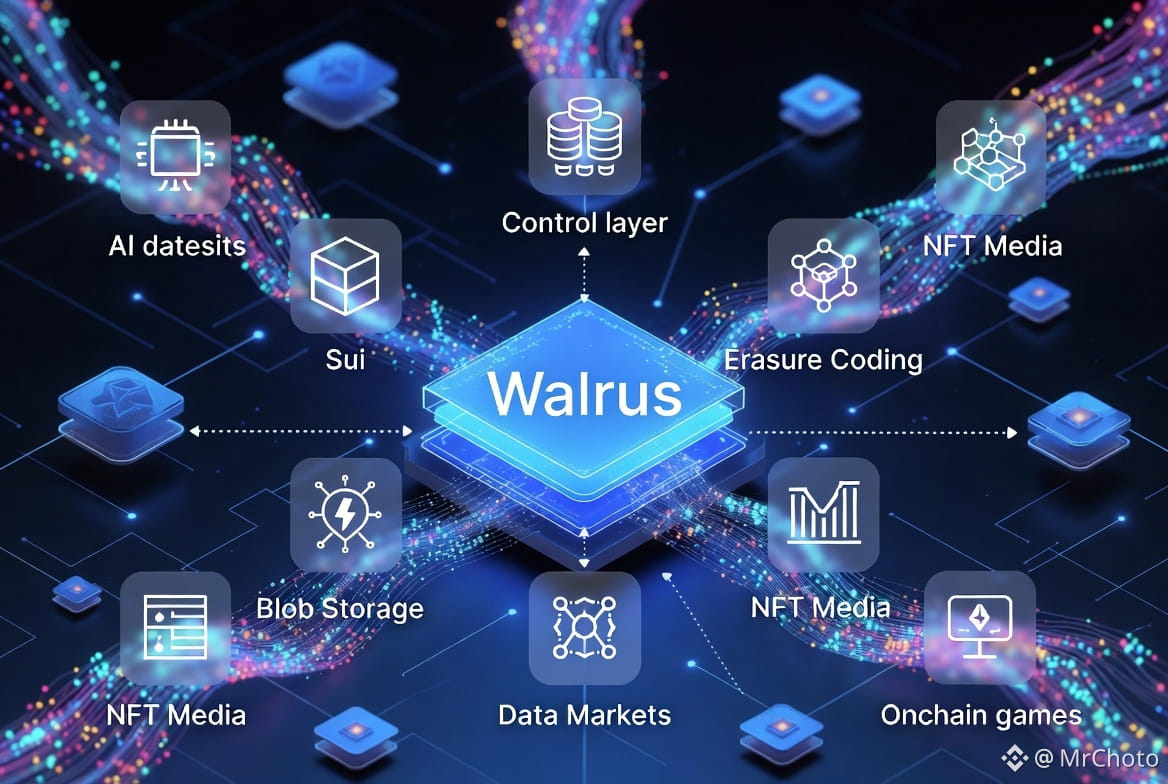

In the middle of 2024, Mysten Labs released Walrus, a decentralized storage and data availability protocol based on "blob" storage with Sui serving as the control layer. The concept is crucial: Walrus relies on Sui for lifecycle management, incentives, and governance and concentrates engineering effort on the storage network itself rather than creating an entirely new blockchain for storage coordination. In its launch, Mysten presented it as storage intended for big binary files rather than little onchain entries.

From the standpoint of traders and investors, branding wasn't the most important signal. Delivery and timing were key. Walrus formalized research on arXiv in 2025 after releasing a technical whitepaper outlining its design and efficiency methods in September 2024. The key turning point came on March 27, 2025, when Walrus launched on the mainnet, transitioning from experimental storage promises to a live system where storage and retrieval are truly taking place under production settings..

What what is different in this situation, then?

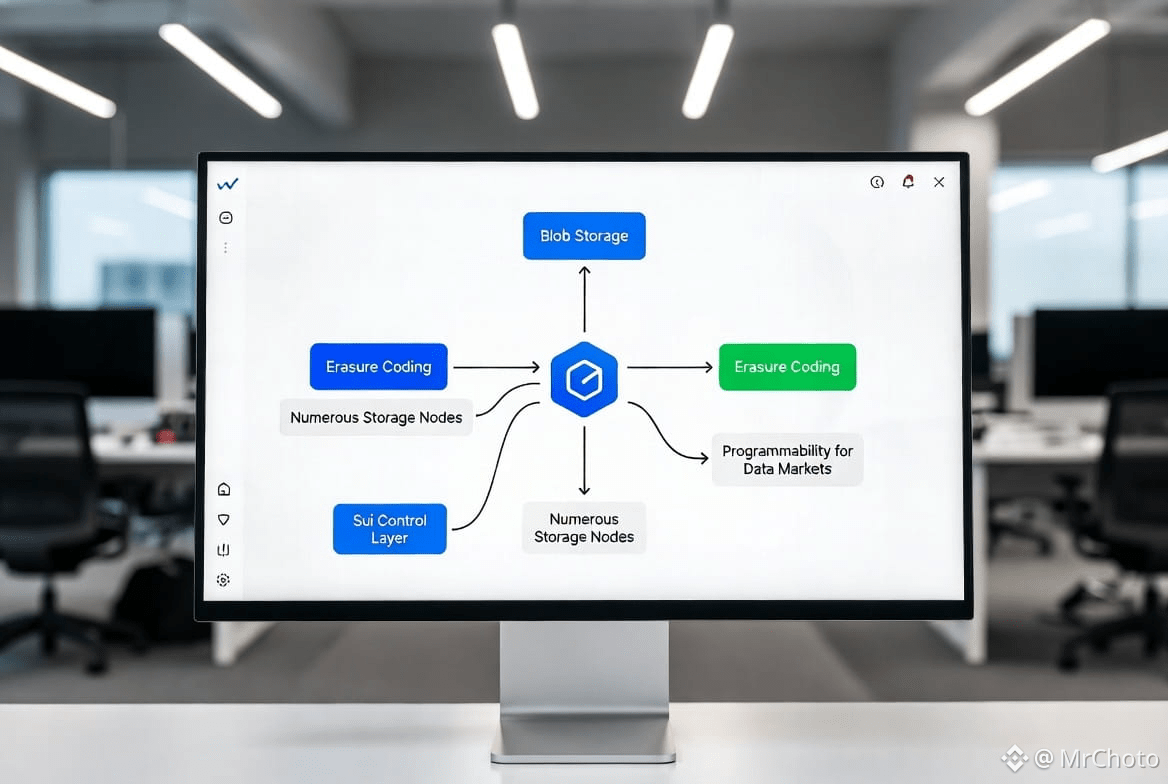

One of two mental models—replication (store copies everywhere, high cost) or "cheap but uncertain" networks, which can be difficult to reason about operationally—is how most people conceptualize decentralized storage. Walrus adopts a more infrastructure-style strategy, dividing data into pieces over numerous storage nodes via erasure coding. As long as there are enough fragments available, the network can still rebuild the original blob even if some nodes go offline or even act maliciously. According to the whitepaper, this is an effort to achieve high resilience at a scale of hundreds of storage nodes with less overhead than complete replication.

This may sound theoretical, but when you apply it to real-world applications, uptime, durability, and cost curves become important.

You need assurance that files won't vanish, links won't deteriorate, and expenses won't sporadically increase if you're developing anything that provides consumers with NFT media, gaming assets, AI datasets, legal documents, financial records, and social content. A storage network soon becomes costly if it requires excessive replication to be secure. It is useless for severe applications if it is too delicate. Walrus is specifically designed to balance maintaining robust availability assumptions with a storage overhead that is manageable enough to be utilized like actual infrastructure.

Programmability is the other undervalued component. Walrus is more than just a location to "dump files." It is creating storage within the Sui ecosystem that can be verified, referenced, and engaged with in organized ways. This is significant because the next generation of applications, particularly those that are related to AI, do not treat data as static. They treat data as having lifecycle events, pricing, rules, and access patterns. Walrus presents itself as facilitating "data markets" in which governability and dependability are features rather than afterthoughts.

Let's get painfully realistic now: is it feasible to implement on a large scale?

A practical aspect that most marketing pages won't inform you can be found in Walrus's own SDK documentation. In a direct node interaction pattern, writing and reading blobs might involve a significant number of requests—roughly 2200 to write a blob and 335 to read one (though an upload relay can minimize write overhead). This does not imply that the system is flawed; rather, it indicates that Walrus is carrying out actual distributed work—fragmentation, distribution, certification, and reconstruction—under the hood. However, it also serves as a reminder to investors of the operational difficulty of decentralized infrastructure and the importance of usability tools in addition to cryptography.

Additionally, the cost structure resembles "real infrastructure economics" rather than DeFi. WAL token fees for storage operations and SUI gas fees for onchain transactions coordinating lifecycle events are the two cost components of storage on the Walrus mainnet. Small blobs can be disproportionately expensive because fixed per-blob metadata dominates below certain sizes (they mention roughly 64MB as a crucial threshold in cost behavior). Their documents even provide a cost calculator. This type of restriction influences actual product design and increases the network's investability due to its transparency.

What makes Walrus relevant in 2026 instead of just being another storage experiment?

Due to the fact that decentralized storage is gradually becoming mandatory. Model artifacts and datasets are necessary for AI applications. Asset persistence is necessary for onchain games. Document integrity and audit trails are becoming more and more important in tokenized finance. Additionally, robust media hosting is necessary for social apps. The "decentralization" argument falls apart at the first subpoena, outage, or platform policy change if these things are totally dependent on centralized storage.

One of the most obvious attempts to address that as a system rather than a meme is Walrus. Instead of reimagining government, it uses a contemporary chain (Sui) for cooperation. Instead of using naïve replication, it employs erasure coding. Its expenses are specified. On March 27, 2025, the mainnet was shipped.

My personal conclusion is straightforward: Walrus's decentralized structure makes it uninteresting. It's intriguing because it aims to make decentralized storage uninteresting and dependable enough for developers to stop arguing over the ideology and begin using it as a regular component.

Additionally, as infrastructure becomes commonplace, hype cycles no longer provide value. It is a result of usage.

Walrus isn't vying for storylines, which is the true investing angle. It is vying for permanency.