Most of us only think about storage when it embarrasses us.

A link you shared with confidence goes dead. A folder you trusted gets “reorganized” by a platform that never asked permission. A file you uploaded for safety comes back slightly different, and you can’t even prove when the change happened. Or worse: you’re building something that depends on data—an app, a model, a marketplace—and you realize the scary part isn’t losing the data. The scary part is losing the truth of the data. What version was it? Who had access? Was it still available when it mattered? Could someone quietly rewrite history and call it a “bugfix”?

Walrus feels like it was designed by people who’ve had that sinking feeling and decided they never wanted to feel it again.

At its heart, Walrus isn’t trying to be a louder cloud. It’s trying to be a calmer one. A storage layer that doesn’t ask you to “trust the service,” but gives you a way to know what’s stored, prove it hasn’t changed, and verify it stays available—without turning the cost into a joke only speculators can afford. And it does this by making storage look less like a black box and more like a contract: a commitment you can point to, hold accountable, and build on.

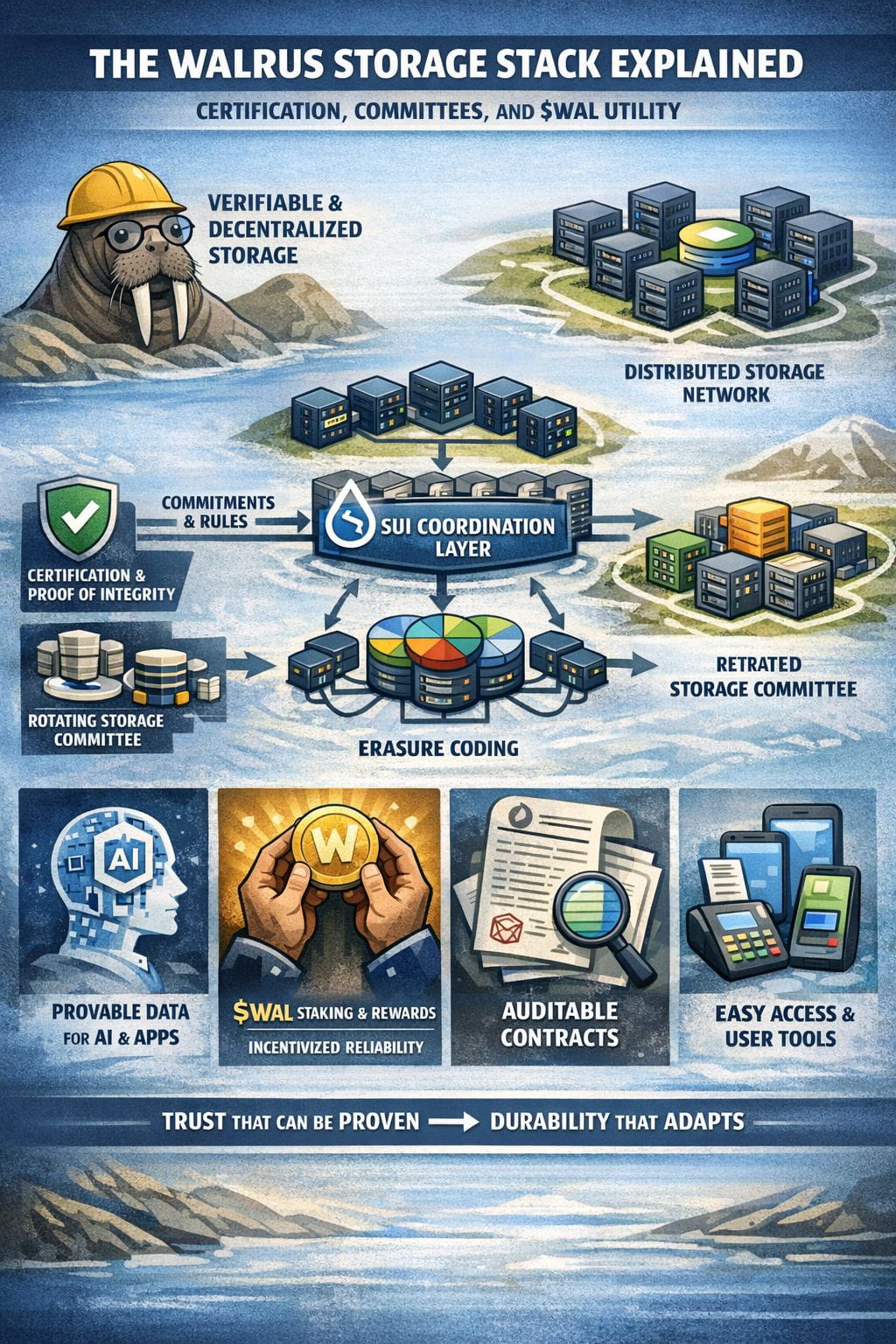

The architecture choice that makes everything click is the split between coordination and bytes. Walrus uses Sui as the place where coordination lives—where storage commitments are represented, where payments and rules can be enforced, and where “this blob exists and is under responsibility until X” becomes something your application can reason about. The data itself—the heavy part, the actual content—lives across a committee of storage nodes that rotate over time. That sounds technical, but the human meaning is simple: Walrus doesn’t want durability to depend on one operator, one company, one “promise,” or one permanent set of machines. It wants durability to survive reality: people leaving, nodes failing, networks lagging, incentives changing, and the messy churn that kills most decentralized dreams slowly and quietly.

This is where “certification” stops being a fancy word and becomes the emotional center of the whole design.

In the normal world, storage works like this: you upload, you pay, and then you hope. Hope the provider stays honest. Hope the file still exists tomorrow. Hope nobody “optimizes” your content out of existence. Hope you can prove anything if there’s a dispute.

Walrus aims for something sturdier: you upload, you pay, and you get an outcome that behaves like evidence. Not just “I stored it,” but “here’s a verifiable identity for what I stored, and here’s an auditable commitment that the network took responsibility for serving it.” That might sound abstract until you imagine where storage is heading: AI training data, public records, marketplaces for media, compliance archives, onchain apps that reference offchain content, and systems where the arguments aren’t about whether the data exists, but about which data existed at a specific time. Certification is how storage becomes usable in a world where accountability matters more than convenience.

Committees and epochs—the rotating operator set—can feel like an implementation detail, but they’re actually Walrus admitting a truth most people avoid: decentralized storage doesn’t just fight attackers, it fights entropy. A network that lasts has to survive change. Operators come and go. Hardware fails. Connectivity fluctuates. Governance evolves. The committee model is Walrus turning that chaos into structure. There is a clear set of responsible parties at any point in time, selected through stake, bound by incentives, and measured by performance. Responsibility isn’t vague. It’s assigned.

And that’s exactly why $WAL matters. Because incentives are where good ideas either become reality or become a museum exhibit.

$WAL is the mechanism that makes “responsibility” expensive to fake. WAL holders can delegate stake to storage nodes. Stake influences who becomes part of the committee. And the committee is the group expected to actually keep blobs available. Rewards are tied to participation and performance, and the system is designed so delegators and operators both have a reason to care about reliability, not just optics. In plain language: if you want to be trusted with storage responsibilities, you should have something at risk, and you should be rewarded for doing the job well. That’s the only way a decentralized network stays dependable without begging people to behave.

Underneath that economic layer is the technical part Walrus is betting on: erasure coding. Instead of copying full data over and over like a blunt instrument, Walrus encodes data into pieces and spreads those pieces across the committee so the blob can still be recovered and served even when some nodes fail or misbehave. The reason this matters isn’t because “coding theory is cool.” It matters because cost is destiny. If decentralized storage is priced like a luxury, it will always be a niche. Walrus is trying to bend the cost curve into something that can support real workloads while still keeping availability strong under faults.

But the most honest part of Walrus, in my view, is that it doesn’t pretend the last mile is trivial. Distributed storage can be brutal for real devices. A browser can’t comfortably handle the sheer number of network requests that a shard-based storage write might require. Mobile connections are flaky. Developers don’t want to build “upload engineering” before they build their product. Walrus leans into practical tooling—relays, SDK improvements, smoother paths for end-user payments—because the network doesn’t win when the protocol is elegant. It wins when using it feels normal.

And this is where Walrus’ broader identity starts to come into focus. It’s not just fighting for a storage market. It’s fighting for a new default assumption: that data should be verifiable, not just accessible. That the history of a blob should be provable. That access control should be designed, not bolted on. That when value depends on data—AI, marketplaces, finance, media—storage shouldn’t be a trust fall.

That doesn’t mean the hard questions go away. Any delegated-stake committee system has to wrestle with gravity: stake concentration, convenience delegation, the temptation to treat “big” as “safe.” Walrus can add performance incentives, accountability mechanisms, and friction against manipulative stake movements, but the long-term shape still depends on whether the ecosystem develops healthy habits. Do delegators diversify? Do operators compete on reliability and service instead of brand? Do users demand proofs, or do they settle for comfort? Decentralization at scale is less like a switch and more like a posture you must keep choosing.

Still, when I step back, the story Walrus is trying to tell feels surprisingly grounded. Committees exist so responsibility is real. Certification exists so trust is portable. Wal exists so reliability isn’t a moral request—it’s a rational outcome. If Walrus succeeds, it won’t be because it stored a lot of data. It will be because it made storage feel like something you can lean on without flinching—because it turned “availability” into a promise that can be proven, and turned “trust” into a system that can be audited. In a world that’s getting louder, faster, and more synthetic by the day, that kind of quiet certainty is not a feature. It’s the difference between building something fragile and building something that lasts.