@Walrus 🦭/acc There’s a certain rhythm to decentralized storage that you don’t really notice until you try to describe it to someone else. In Walrus, that rhythm is explicit: time is chopped into epochs, and a committee of storage nodes is responsible for keeping data available during each epoch. That “clock-and-committee” framing is a big part of why the protocol has been showing up in more conversations lately—because it turns a messy, always-on problem (people come and go, networks glitch, nodes fail) into something the system can reason about in scheduled steps, without pretending the internet is perfectly reliable.

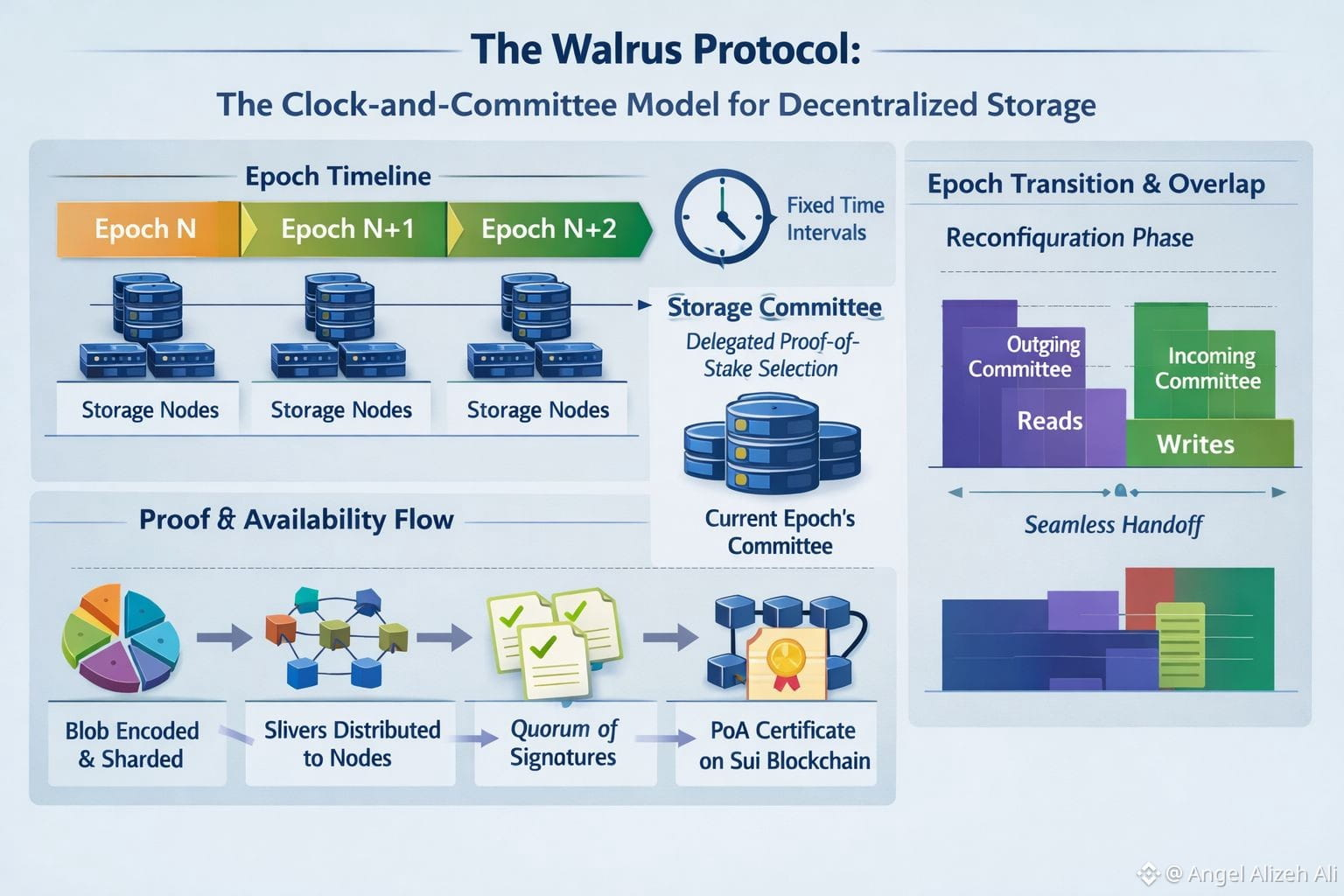

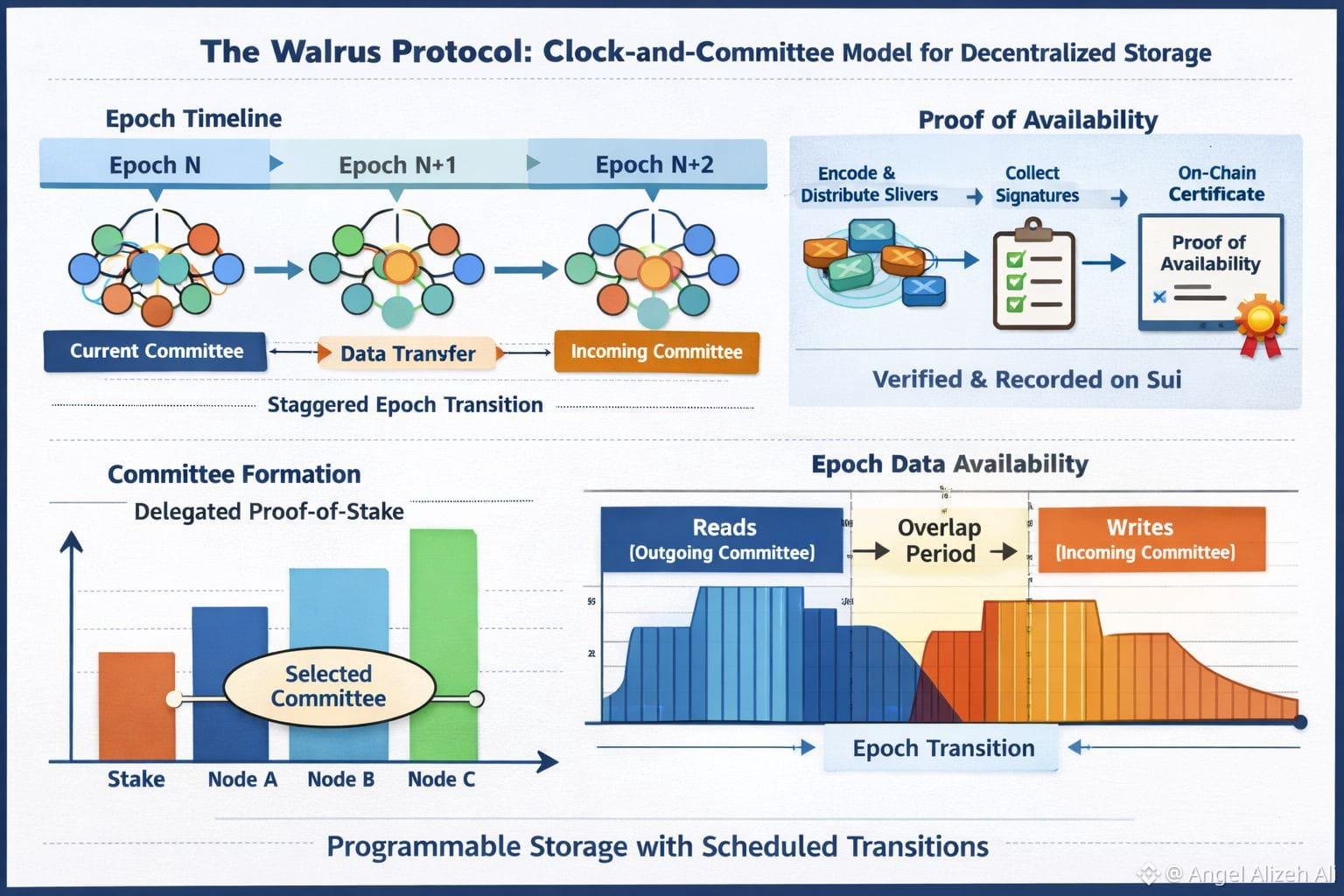

The “committee” piece is fairly intuitive once you stop thinking about storage as a vague cloud and start thinking about it as a job assignment. Walrus is operated by a delegated proof-of-stake model in which stake influences who ends up in the storage committee for an epoch. In the whitepaper, you can see the protocol’s baseline assumption: epochs have a static set of storage nodes, and a committee is formed based on how storage shards are assigned for that epoch (with the usual Byzantine-fault tolerance framing in the background). The practical consequence is that the network always has a current roster—an accountable group—rather than an undefined crowd.

The “clock” is where it gets more interesting, because time isn’t just for scheduling, it’s for promises. When you store a blob (Walrus’s basic unit of data), you’re not only uploading pieces of it to nodes; you’re also locking in how long that blob should remain available. The protocol leans on Sui as a control plane: metadata and the proof that the blob is available live on-chain, while the blob content itself stays off-chain on storage nodes. The write flow is deliberately ceremony-like: a client encodes the blob into redundant “slivers,” distributes them to the current committee, gathers a quorum of signed acknowledgements, and then publishes that certificate on Sui as a Proof of Availability. That on-chain certificate is the moment the system treats availability as real, not merely hoped for.

But the part that makes the clock-and-committee model feel like more than governance theater is what happens at the edges of time—epoch transitions. Most storage networks get awkward here. If you swap out who’s responsible for data, you risk a window where nobody’s clearly responsible, or where reads and writes race each other into confusion. Walrus tackles this with a staged transition approach described in its technical writing: during reconfiguration, writes are pushed to the incoming committee while reads can continue from the outgoing committee, avoiding a single fragile “handover instant” where everything flips at once. It’s one of those designs that sounds mundane until you remember how many outages, “missing file” moments, and half-synced states in distributed systems come from poorly managed transitions.

Why is everyone talking about this now, rather than letting it become one more clever paper people save and forget? It’s a timing thing, more than anything. More on-chain apps are running into the same wall: blockchains are great at agreement, but they’re not built to hold everyone’s photos, models, videos, and datasets forever. At the same time, AI work and media-heavy apps keep raising the bar for what “storage” even means—people want big files handled reliably, with clear rules around access and retention. Walrus lands right in the middle of that tension: keep the logic and guarantees on-chain, keep the heavy data off-chain. So it naturally shows up in conversations about availability, permanence, and storage that behaves more like a system with commitments than a dumb hard drive. Another part is simple momentum: the project has kept publishing concrete technical explanations (like its Proof of Availability mechanism) and rolling out ecosystem activity, which tends to draw builders first, and then the speculation crowd afterward.

I’ll admit I’m usually skeptical of systems that promise to make storage feel “programmable,” because that word can hide a lot of hand-waving. What I find more grounded here is the way Walrus makes obligations legible: a blob exists, it has metadata that’s checkable, it has a stated lifetime, and there’s a known committee responsible right now. If that committee changes, the protocol doesn’t pretend the change is instantaneous; it plans for overlap. In a space that often tries to wish away messy realities—latency, churn, incentives, human operators—there’s something reassuring about a design that says, plainly, “time passes, membership changes, and we’ll run the system accordingly.”