We say “data is power,” but we rarely ask where that power actually sits.

We say “data is power,” but we rarely ask where that power actually sits.

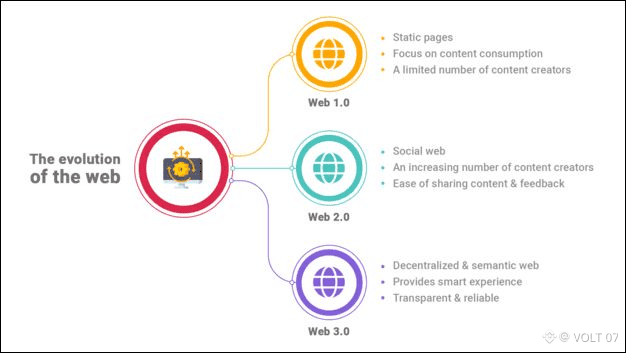

In Web3, decentralization is often treated as a proxy for fairness. If data is distributed, power must be distributed too at least in theory. In practice, power does not follow storage diagrams. It follows control at the moment of consequence.

So the real question is not who stores the data, but:

Who can act on it when it matters most?

That question reframes how Walrus (WAL) should be understood.

Power reveals itself under stress, not under normal operation.

During calm periods, everyone appears empowered:

data is accessible,

retrieval is cheap,

redundancy looks healthy,

incentives feel aligned.

In those moments, control seems evenly distributed.

But when conditions change incentives weaken, urgency spikes, or disputes arise power concentrates quickly:

whoever can retrieve data first,

whoever can withhold it longest,

whoever can delay repair without consequence,

whoever controls the narrative of what “failed.”

Power is not who holds copies.

Power is who shapes outcomes.

Most storage models quietly centralize power during failure.

When things go wrong, many systems default to:

best-effort availability,

social coordination,

off-chain escalation,

“the network will recover.”

In reality, this shifts power upward and outward:

to operators with surplus resources,

to applications that can afford redundancy,

to users who notice early enough to exit,

to whoever can absorb loss without recourse.

Everyone else discovers they were only empowered on good days.

Control over degradation is more powerful than control over data.

A subtle but critical distinction:

Owning data matters less than controlling how its reliability decays.

If a system allows:

silent degradation,

uneven retrieval,

delayed detection,

then power belongs to those who can tolerate ambiguity not to those who depend on correctness.

Walrus is designed around this insight. It treats degradation itself as a power vector that must be constrained.

Walrus distributes power by enforcing consequences early.

Rather than letting power emerge informally during failure, Walrus asks:

Who should feel pressure before users are harmed?

Who should be unable to ignore decay cheaply?

By making neglect costly and visible upstream, Walrus prevents power from pooling downstream among the most resilient or least dependent actors.

This is not ideological decentralization.

It is operational power balancing.

Why “the network” is not a neutral holder of power.

When responsibility is collective, power becomes selective:

some can exit quietly,

some can wait out recovery,

some can influence outcomes through patience or capital,

others are forced to accept loss.

Systems that hide behind “the network” allow power to be exercised without accountability. Walrus rejects this by tying authority to enforceable incentives rather than informal influence.

As Web3 stores real leverage, power asymmetries matter.

When storage underwrites:

financial records,

governance legitimacy,

application state,

AI datasets and provenance,

the question of power becomes unavoidable. Who can stall verification? Who can delay access? Who decides when recovery is “good enough”?

Designs that ignore these questions don’t eliminate power they hide it.

Walrus surfaces it and constrains it.

Power is held by whoever users depend on last.

In most failures, users are the last to find out and the least able to respond. That means power has already shifted away from them.

Walrus inverts this dynamic by:

shortening detection windows,

enforcing accountability before irreversibility,

ensuring recovery remains viable while users still have choices.

This keeps power closer to those who bear the consequences, not those who can delay them.

I stopped asking who “owns” the data.

Because ownership is abstract.

I started asking:

Who controls the timeline of failure?

Who can afford to wait?

Who pays first?

Who explains last?

Under those questions, power becomes visible and design intent becomes clear.

Walrus earns relevance by refusing to let power emerge accidentally during stress. It designs for it explicitly.

If data is power, real decentralization is about who can’t escape responsibility.

Not who has the most copies.

Not who speaks the loudest about decentralization.

But who is forced to act when reliability slips before users lose leverage.

Walrus chooses to bind power to consequence, not convenience. That is not just fairer. It is more honest.