People often talk about Web3 as if it is made of transactions. But the web we actually use is made of files. Pages, images, models, videos, datasets, proofs, reports, archives. The heavier the thing, the less it wants to live inside a blockchain. And yet the heavier the thing, the more we wish it had a reliable home that does not depend on one company staying kind, solvent, and online.

@Walrus 🦭/acc is built in that gap. It is a decentralized storage protocol designed for large, unstructured content called blobs. A blob is simply a file or data object that is not stored like rows in a database table. Walrus supports storing blobs, reading them back, and proving and verifying their availability. It is designed to keep data retrievable even if some storage nodes fail or behave maliciously, a class of problems often described as Byzantine faults. Walrus uses the Sui blockchain for coordination, payments, and availability attestations, while keeping blob contents off-chain. Walrus is explicit that only metadata is exposed to Sui or its validators, not the blob content itself.

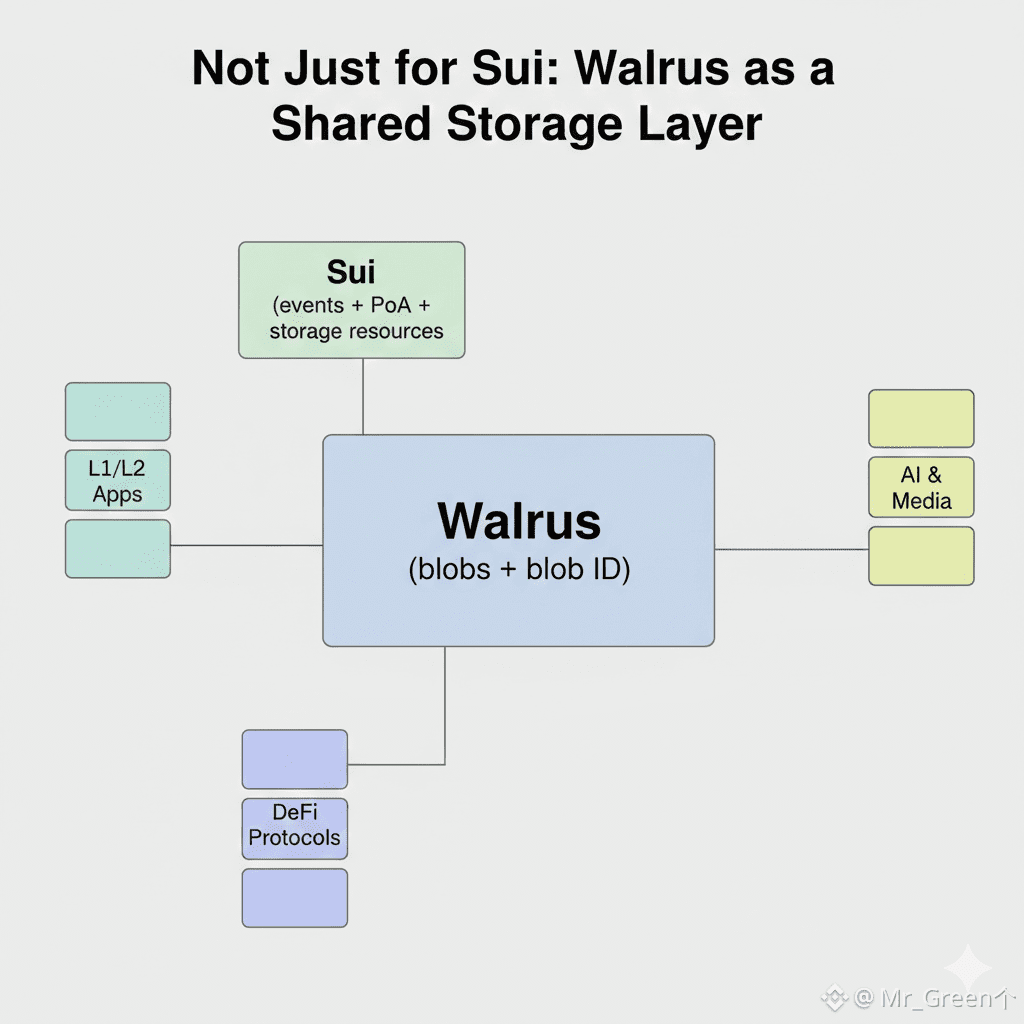

The phrase “not just for Sui” matters here, because Walrus is not trying to be a storage feature for one ecosystem. It is trying to be a storage layer that any builder can lean on, even if their application lives elsewhere. Walrus is meant to be used “in conjunction with any L1 or L2 blockchains” for experiences that need large data stored and, when needed, certified as available in a decentralized way. That idea sounds simple, but it changes how you design apps. Instead of asking, “Can my chain store this file?” you ask, “Can my app store this file somewhere decentralized, then prove it is available when it needs to be?”

The first thing Walrus standardizes is identity. In ordinary web storage, a file is often identified by a link. Links are convenient, but they are fragile. They can rot. They can redirect. They can quietly point to something else. Walrus anchors blobs to a blob ID, a cryptographic identifier derived from the encoded data and metadata. Under the hood, Walrus describes hashing the shard representations and committing them using a Merkle tree structure so individual parts can be authenticated against a single root. A Merkle tree is a way to commit to many pieces of data under one root hash, while still allowing later verification that a piece belongs to that commitment. In plain terms, the blob ID is a seal. You can retrieve data from a node, a cache, or an aggregator, and still verify you received the same thing the writer intended.

The second thing Walrus standardizes is the moment of responsibility. Storage systems often feel permanent until the day they do not. Walrus tries to make availability legible. It defines the Point of Availability (PoA), which marks when the system takes responsibility for maintaining a blob’s availability. It also defines an availability period, which specifies how long the blob will be maintained after PoA. Both are observable through events on Sui. This is an important shift in tone. Instead of “trust us, it’s there,” you get “here is the on-chain moment the system accepted responsibility, and here is how long that responsibility lasts.”

That is also where it is worth being precise about the word “permanent.” Walrus does not claim magical forever storage. It models storage as time-bound, renewable responsibility. You can store a blob for a period, verify PoA, and extend its lifetime later by adding more storage resources. In real systems, that is often the honest version of permanence: not an eternal promise, but a structure where continued availability is possible as long as the resources exist to pay for it.

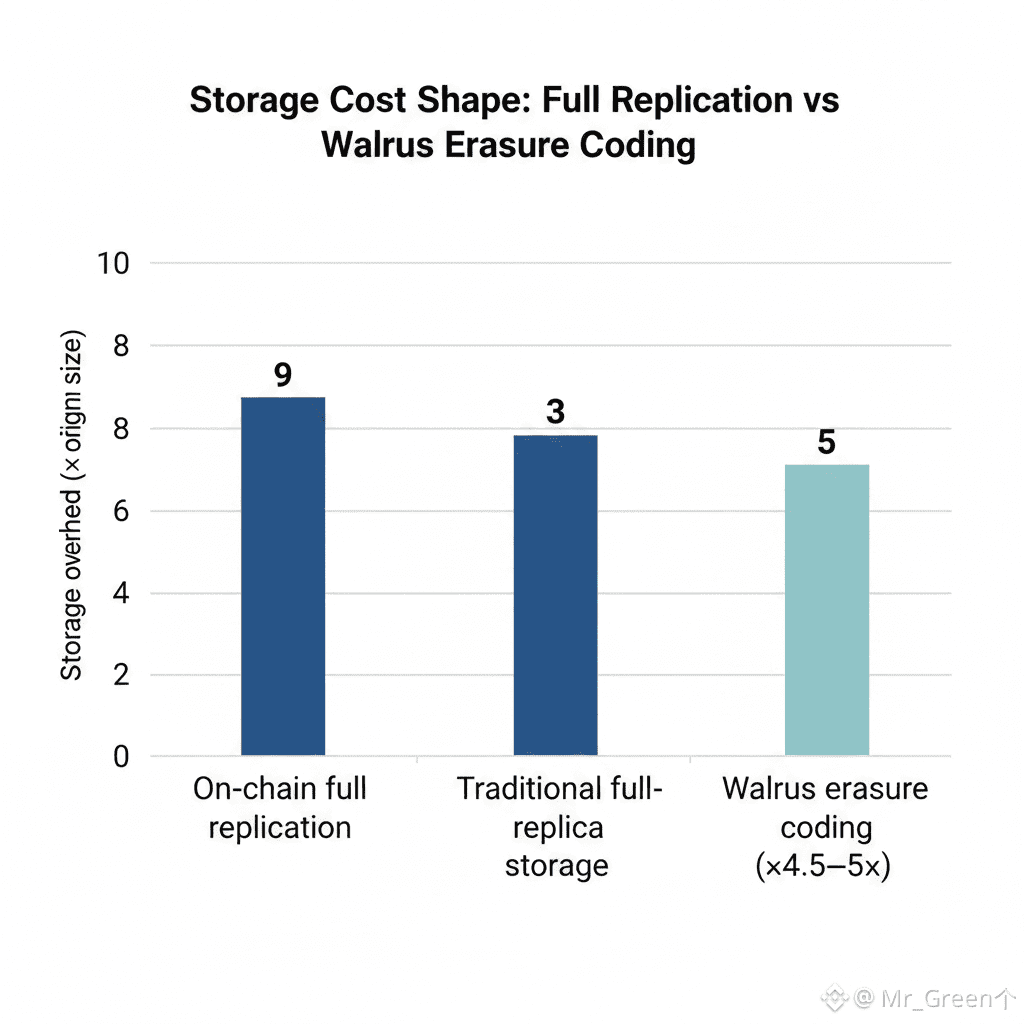

The third thing Walrus standardizes is affordability at scale. This is where the design steps away from full replication and toward erasure coding. Walrus uses a bespoke erasure code construction called RedStuff, and on Mainnet it uses Reed–Solomon codes under the hood. Erasure coding takes a blob and turns it into a larger set of encoded pieces with redundancy, so the original can be reconstructed even if some pieces are missing. Walrus describes an expansion of blob size by about 4.5–5×, and notes this overhead is independent of the number of shards and storage nodes. That matters because it makes costs more predictable. You are paying a fixed multiple for resilience, rather than copying the full blob many times as the network grows.

Walrus then makes that redundancy operational. Encoded pieces are grouped into slivers, slivers are assigned to shards, and shards are managed by storage nodes during a storage epoch. On Mainnet, Walrus describes storage epochs lasting two weeks. Walrus assumes that more than 2/3 of shards are managed by correct storage nodes within each epoch, tolerating up to 1/3 Byzantine shards. This is the practical meaning of “high availability even in the presence of Byzantine faults.” The system does not need every node to behave. It needs enough of the system to behave, and it is engineered around that threshold.

None of this works if the chain has to carry the blob. Walrus is strict about that separation. The chain is used for what chains are good at: coordination, ownership, payments, and public attestations. Walrus describes storage space as a resource on Sui that can be owned, split, merged, and transferred. Stored blobs are represented by objects on Sui in the sense that contracts can check whether a blob is available and for how long, extend its lifetime, or optionally delete it. That’s a very “programmable storage” idea, but it stays lightweight because it’s metadata and lifecycle rules, not the raw data.

This is also why “not just for Sui” is believable. If your app lives on another chain, you can still use Walrus as the storage layer and then use Walrus’s verifiable signals—blob IDs and PoA events, as the anchor for trust. The application can treat Walrus as the place where large data lives, while the application’s own chain or off-chain logic decides what to do with that data. Walrus even frames some use cases explicitly in cross-ecosystem terms, such as supporting data availability for L2s, where parties need to certify that blobs are stored and available to all.

Walrus also does not force builders to abandon the web’s existing delivery patterns. It supports a CLI, SDKs, and Web2 HTTP technologies. It describes optional infrastructure like aggregators, which reconstruct blobs from slivers and serve them via HTTP, and caches, which add caching to reduce latency and load. This matters because users still want websites that load quickly. Walrus doesn’t try to replace CDNs. It tries to remain compatible with CDNs while keeping the underlying content verifiable for clients that want to check.

The protocol also draws clear boundaries around what it is not. Walrus does not reimplement a full smart contract platform. It relies on Sui smart contracts to manage resources and processes. Walrus also supports encrypted blobs, but it does not claim to be a key management system. That is an important distinction for privacy. Walrus can store sealed data, but it does not pretend to decide who holds the keys. For builders, that means you can pair Walrus with your own access control and key infrastructure without being locked into one privacy scheme.

When you look at the use cases Walrus lists, you can see the same theme repeating: store big things, keep them verifiable, keep them available long enough to matter. It highlights AI-related use cases like storing training datasets, models, weights, and outputs. It highlights NFT and dApp media like images, video, and game assets. It describes long-term archives of blockchain history, and it describes decentralized web experiences where a site’s resources can be hosted in a decentralized way.

Walrus’s move to Mainnet reinforces that it is trying to be production infrastructure. It announced Mainnet as live on March 27, 2025, described a decentralized network of over 100 storage nodes, and said Epoch 1 began on March 25, 2025. It also described practical additions like TLS handling for storage nodes, improved expiry handling in the CLI, and a shift to Reed–Solomon codes for RedStuff.

So does Walrus “set the standard” for storage? The safer way to say it is this: Walrus lays down a clear pattern that many Web3 systems have needed for a long time. Keep large content off-chain, but make its identity and availability verifiable. Treat availability as a time-bound commitment with a public start point. Make cost predictable enough that multi-GB data is not a special case. Stay compatible with the web so builders can ship products people actually use.

In a space where storage has often been either too expensive to scale or too centralized to trust, that pattern is not flashy. It is simply useful. And in infrastructure, usefulness is often what survives.