Infrastructure looks different from the operator’s side

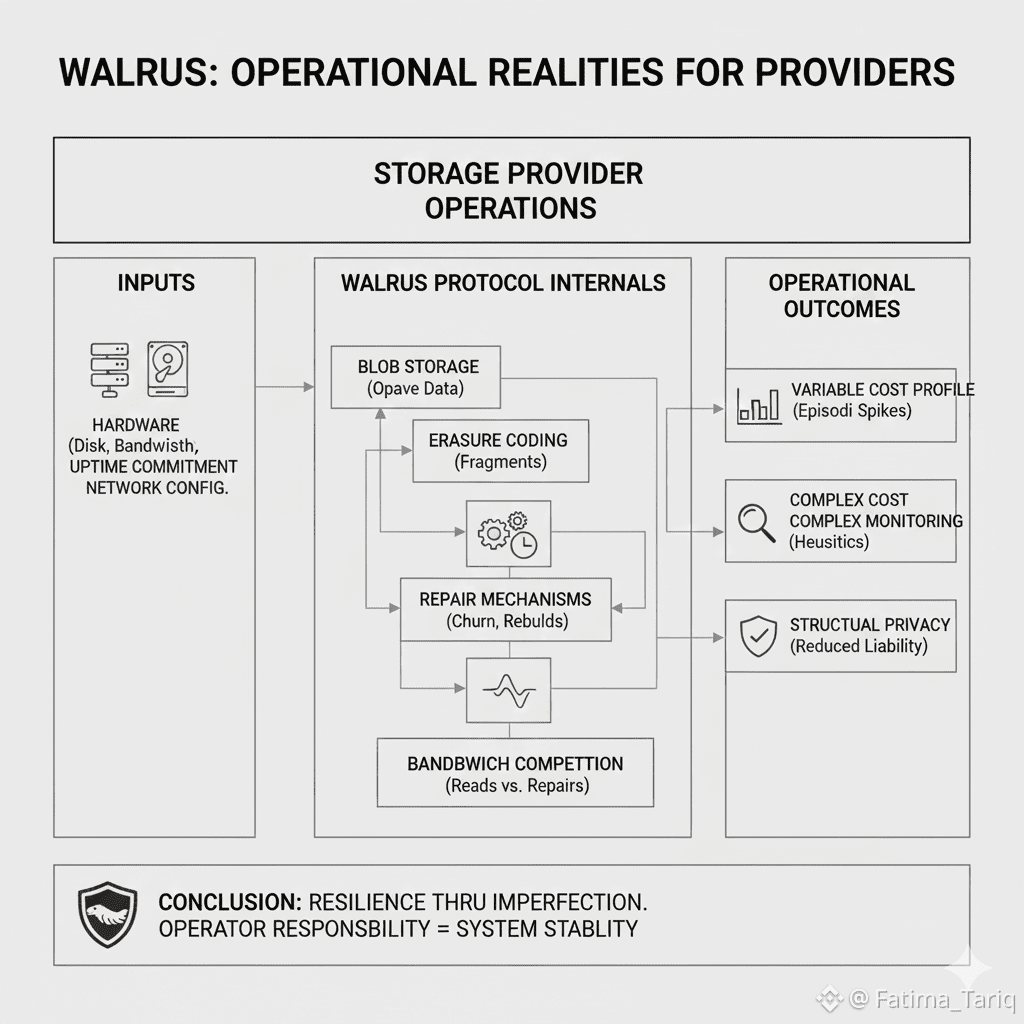

Decentralized storage protocols are often evaluated from the perspective of users and applications: how durable the data is, how quickly it can be retrieved, and how well the system resists censorship or central control. Less attention is paid to the operational reality faced by storage providers—the participants who supply disk space, bandwidth, and uptime in exchange for protocol‑level rewards.For systems like Walrus, storage providers are not passive warehouses. They are active participants in a continuously adapting network. Their operational decisions—hardware choices, network configuration, maintenance schedules—directly influence system reliability. Understanding Walrus as infrastructure therefore requires examining how it behaves when run by real operators under real constraints, not idealized assumptions.This perspective reveals where design choices reduce burden, where they shift it, and where hidden costs emerge over time.

Blobs simplify policy, not operations

Walrus stores data as opaque blobs. From a protocol standpoint, this is a deliberate simplification. The system does not interpret content, enforce usage rules, or prioritize one blob over another. Storage providers are not required to understand what they are storing, only to make fragments available when requested.Operationally, this neutrality is a mixed outcome. Providers benefit from reduced compliance surface. They do not need to filter content or enforce application‑level logic. At the same time, they lose visibility into workload intent. A fragment requested once a year is treated the same as one requested every minute.This lack of differentiation complicates capacity planning. Providers must provision for peak demand without knowing which stored data will become hot, when, or why. The protocol’s simplicity shifts forecasting complexity onto operators.

Erasure coding changes the cost profile

Walrus relies on erasure coding to reduce storage overhead. Instead of storing full replicas, providers store fragments that contribute to a larger recovery set. This design lowers disk requirements and allows smaller operators to participate without massive storage investments.However, erasure coding replaces disk cost with bandwidth and coordination cost. A fragment is cheap to store but expensive to serve during reconstruction or repair. Providers experience this most clearly during periods of churn or network instability.When fragments disappear elsewhere in the network, remaining providers may receive increased repair traffic. This traffic is not user‑driven and cannot be predicted from access patterns alone. Operators must absorb these bursts while maintaining acceptable performance for user reads.The result is a cost structure that is less linear and more episodic than traditional replicated storage.

Repair traffic is unavoidable and uneven

Repair is not an edge case in Walrus. It is a core operational function. As nodes leave or fail, missing fragments must be regenerated and redistributed to maintain recovery thresholds.For providers, this means background traffic that persists regardless of user demand. Repair operations consume outbound bandwidth, disk I/O, and CPU. They also occur during unfavorable conditions—after failures, during congestion, or when multiple nodes churn simultaneously.Importantly, repair load is not evenly distributed. Providers with higher uptime, better connectivity, or more reliable hardware tend to shoulder more responsibility. Over time, this can create asymmetry: the most dependable operators carry disproportionate operational cost.Walrus does not hide this reality. It accepts that resilience depends on some participants doing more work than others.

Churn is operational noise, not an exception

In centralized systems, churn is often treated as a failure state. In decentralized networks, it is the baseline. Operators reboot machines, migrate infrastructure, or temporarily shut down to manage costs.Walrus assumes churn and designs around it. From an operator’s perspective, this means that joining the network does not require perfect uptime, but staying competitive does. Providers with frequent downtime trigger repairs that increase load elsewhere, potentially reducing their own effective contribution.This creates an implicit incentive structure. Operators who invest in stability reduce overall system strain and indirectly benefit themselves by avoiding repair penalties or degraded performance. However, these incentives are indirect and emerge through system behavior rather than explicit enforcement.Operating Walrus infrastructure is therefore less about compliance with rules and more about alignment with network dynamics.

Bandwidth is the limiting resource

For most providers, disk is cheap. Bandwidth is not.Walrus exposes this reality. Reads, repairs, and redistributions all compete for network capacity. Under light load, this competition is invisible. Under stress, it becomes the dominant operational concern.Providers must decide how to allocate bandwidth between user traffic and protocol maintenance. Prioritizing one degrades the other. Over‑provisioning bandwidth increases fixed costs. Under‑provisioning risks missed requests and degraded reputation within the network.These decisions are local, but their effects are systemic. When many providers make similar trade‑offs, network‑wide performance shifts. Walrus does not coordinate these choices centrally. It allows them to play out organically, accepting variability as the cost of decentralization.

Overlapping reads and repairs complicate monitoring

From the operator’s side, reads and repairs are difficult to distinguish. Both arrive as fragment requests. Both require timely response. During busy periods, the mix changes dynamically.This complicates monitoring and alerting. Spikes in traffic may indicate legitimate user demand, network instability elsewhere, or cascading repair activity. Reacting incorrectly—by throttling or delaying traffic—can amplify problems rather than resolve them.Operators therefore rely on heuristics rather than certainty. Over time, experienced providers learn to recognize patterns, but this knowledge is tacit and unevenly distributed. Walrus benefits from this human adaptation, even though it cannot formalize it at the protocol level.

Human shortcuts shape system behavior

Storage providers are not neutral actors. They optimize for cost, convenience, and risk. Maintenance may be delayed. Capacity upgrades may be postponed. Redundancy may be minimized.These shortcuts are rational in isolation, but cumulative in effect. When many providers defer investment simultaneously, repair frequency increases. When bandwidth margins shrink, contention worsens. When monitoring is relaxed, outages last longer.Walrus absorbs these behaviors rather than preventing them. The system is resilient because it expects imperfection. But resilience has limits. Beyond a certain point, degraded operator behavior becomes visible as latency, repair backlogs, or temporary unavailability.Understanding Walrus means accepting that human behavior is part of the threat model.

Privacy and liability from the operator’s view

For storage providers, privacy is both a protection and a constraint. Storing encrypted fragments reduces liability and compliance burden. Operators are not custodians of intelligible content.At the same time, neutrality removes discretion. Providers cannot selectively refuse storage based on content type. They must trust the protocol’s abstraction to shield them from downstream responsibility.Under load, increased repair and read traffic may draw attention, even if content remains opaque. Operators must be comfortable with this visibility, understanding that decentralization limits their control over how and when they participate in network activity.This trade‑off is foundational. Walrus prioritizes structural privacy over operator agency.

Strengths without operational illusions

Walrus does not assume ideal operators. Its design acknowledges uneven uptime, heterogeneous infrastructure, and rational cost‑cutting. Erasure coding reduces disk burden. Blob abstraction simplifies policy. Repair mechanisms preserve durability without centralized oversight.For disciplined operators, this creates an environment where good behavior is rewarded indirectly through stability and reduced intervention. For less disciplined operators, participation remains possible, but impact is diluted.The protocol’s strength lies in accommodating this spectrum rather than enforcing uniformity.

Where operational friction accumulates

As the network scales, small frictions add up. Repair traffic grows faster than stored data. Bandwidth costs dominate margins. Monitoring becomes probabilistic rather than precise.These pressures do not invalidate the system, but they define its sustainable operating range. Walrus is not a “set and forget” environment for providers. It requires ongoing attention, adaptation, and realistic expectations about cost and effort.Operators expecting passive income will likely be disappointed. Operators approaching Walrus as infrastructure work will find its behavior predictable, if demanding.

A grounded conclusion

From the storage provider’s perspective, Walrus is neither frictionless nor fragile. It is a system that trades centralized simplicity for distributed resilience, shifting operational complexity onto those closest to the hardware.This shift is intentional. It aligns incentives with reliability and accepts that decentralization functions through imperfect participants rather than ideal ones. The result is a network that degrades gradually rather than catastrophically.Evaluated honestly, Walrus offers a credible operational model for decentralized blob storage, provided providers understand that efficiency at the protocol level translates into responsibility at the operator level. In infrastructure, that trade‑off is not a flaw. It is the cost of realism.